Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City (24 page)

Read Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City Online

Authors: Hilary Sumner-Boyd,John Freely

Tags: #Travel, #Maps & Road Atlases, #Middle East, #General, #Reference

A short distance beyond Atik Ali Pa

ş

a Camii, on the same side of the avenue, we come to the külliye of Koca Sinan Pa

ş

a, enclosed by a picturesque marble wall with iron grilles. The külliye consists of a medrese, a sebil and the türbe of Koca Sinan Pa

ş

a, who died in 1595. Koca Sinan Pa

ş

a was Grand Vezir under Murat III and Mehmet III and was the conqueror of the Yemen. Perhaps the most outstanding element in this very attractive complex of buildings is the türbe, a fine structure with 16 sides, built of polychrome stonework, white and rose-coloured, and with a rich cornice of stalactites and handsome window mouldings. The medrese, which we enter by a gate in the alley alongside, has a charming courtyard with a portico in ogive arches. The sebil, too, is an elegant structure with bronze grilles separated by little columns and surmounted by an overhanging roof. The whole complex was built in 1593 by Davut A

ğ

a, the successor to Sinan as Chief Architect.

On the other side of the alley across from the sebil, a marble wall with grilles encloses another complex of buildings, the külliye of Ali Pa

ş

a of Çorlu. This Ali Pa

ş

a was a son-in-law of Mustafa II and was Grand Vezir under Ahmet III, on whose orders he was beheaded in 1711 on the island of Mytilene. Ali Pa

ş

a’s head was afterwards brought back to Istanbul and buried in the cemetery of his külliye, which had been completed three years earlier. This külliye, consisting of a small mosque and a medrese, belongs to the transition period between the classical and the baroque styles. Though attractive, there is nothing especially outstanding about these buildings, although one might notice how essentially classical they still are. The only very obvious baroque features are the capitals of the columns of the porch.

Directly across the avenue we see the octagonal mosque of Kara Mustafa Pa

ş

a of Merzifon, together with a medrese and a sebil. This unfortunate Grand Vezir also lost his head, which, according to an Ottoman historian, “rolled at the feet of the Sultan (Mehmet IV) at Belgrade” after the unsuccessful second siege of Vienna in 1683, of which Kara Mustafa had been in charge. The buildings were begun in 1669 and finished by the Pa

ş

a’s son in 1690. This mosque is of the transitional type between classic and baroque and is of interest chiefly as one of the few octagonal buildings to be used as a mosque. This külliye and the other two we have just looked at have recently been well restored; Kara Mustafa’s medrese has been converted into an institute commemorating the celebrated poet, Yahya Kemal, who died in 1958.

The street just beyond this little külliye is called Gedik Pa

ş

a Caddesi; this leads to a hamam of the same name at the second turning on the left. This is one of the very oldest baths in the city, built in about 1475, and it is still in operation. Its founder was Gedik Ahmet Pa

ş

a, one of Mehmet the Conquerors Grand Vezirs (1470–7), commander of the fleet at the capture of Azof and conqueror of Otranto. This hamam has an unusually spacious and monumental so

ğ

ukluk consisting of a large domed area flanked by alcoves and cubicles; the one on the right has a very elaborate stalactited vault. The hararet is cruciform except that the lower arm of the cross has been cut off and made part of the so

ğ

ukluk; the corners of the cross form domed cubicles. The bath has recently been restored and now glistens with bright new marble; it is much patronized by the inhabitants of this picturesque district.

THE BEYAZ

İ

D

İ

YE

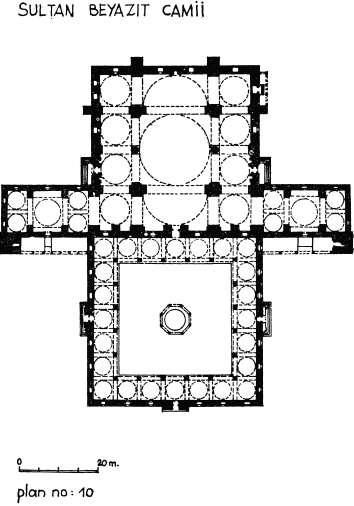

Returning once again to the main avenue, we continue along to Beyazit Square, a confused and chaotic intersection of no recognizable geometric shape. Crossing to the right-hand side of the avenue, we come to the Beyazidiye, the mosque and associated pious foundations of Sultan Beyazit II. The Beyazidiye was the second great mosque complex to be erected in the city. Founded by Beyazit II, son and successor of Mehmet the Conqueror, it was built between 1501 and 1506, and consists of the great mosque itself, a medrese, a primary school, a public kitchen, a hamam and several türbes. Heretofore, the architects name has variously been given as Hayrettin or Kemalettin, but a recent study has shown that the külliye is due to a certain Yakub-

ş

ah bin Sultan

ş

ah, who also built a kervansaray at Bursa. His background is unknown and his origin uncertain, but he may have been a Turk. Whatever his origin, he created a work of the very first importance, both in its excellence as a building and in its historic importance in the development of Turkish architecture. The mosque marks the beginning of the great classical period which continued for more than 200 years. Before this time, Ottoman architects had been experimenting with various styles of mosques and had often produced buildings of great beauty, as in Ye

ş

il Cami at Bursa or Üç

Ş

erefeli Cami at Edirne; but no definite style had evolved which could produce the vast mosques demanded by the glory of the new capital and the increasing magnificence of the sultans. The original mosque of the Conqueror was indeed a monumental building, but as that was destroyed by an earthquake in the eighteenth century, Beyazit Camii remains the first extant example of what the great imperial mosques of the sixteenth and seventeenth century were to be like.

One enters Beyazit Camii through one of the most charming of all the mosque courtyards. A peristyle of 20 ancient columns – porphyry, verd antique and Syennitic granite – upholds an arcade with red-and-white or black-and-white marble voussoirs. The colonnade is roofed with 24 small domes and three magnificent entrance portals give access to it. The pavement is of polychrome marble and in the centre stands a beautifully decorated

ş

ad

ı

rvan. (The core of the

ş

ad

ı

rvan at least is beautiful – the encircling colonnade of stumpy verd antique columns supporting a dome seems to be a clumsy restoration.) Capitals, cornices and niches are elaborately decorated with stalactite mouldings. The harmony of proportions, the rich but restained decoration, the brilliance of the variegated marbles, not to speak of the interesting vendors and crowds which always throng it, give this courtyard a charm of its own.

An exceptionally fine portal leads into the mosque, which in plan is a greatly simplified and much smaller version of Haghia Sophia. As there, the great central dome and the semidomes to east and west form a kind of nave, beyond which to north and south are side aisles. The arches supporting the dome spring from four huge rectangular piers; the dome has smooth pendentives but rests on a cornice of stalactite mouldings. There are no galleries over the aisles, which open wide into the nave, being separated from it only by the piers and by a single antique granite column between them. This is an essential break with the plan of Haghia Sophia: in one way or another the mosques all try to centralize their plan as much as possible, so that the entire area is visible from any point. At the west side a broad corridor divided into domed or vaulted bays and, extending considerably beyond the main body of the mosque, creates the effect of a narthex. This is a transitional feature, retained from an older style of mosque; it appears only rarely later on. At each end of this “narthex” rise the two fine minarets, their shafts picked out with geometric designs in terra-cotta; they stand far beyond the main part of the building in a position which is unique and gives a very grand effect. At the end of the south arm of the narthex, a small library was added in the eighteenth century by the

Ş

eyh-ül Islam Veliyüttin Efendi. An unusual feature of the interior of the mosque is that the sultans loge is to the right of the mimber instead of the left as is habitual; it is supported on columns of very rich and rare marbles. The central area of the building is approximately 40 metres on a side, and the diameter of the dome about 17 metres.

THE PIOUS FOUNDATIONS OF THE BEYAZ

İ

D

İ

YE

Behind the mosque – or, as the Turks say, in front of the mihrab – is the türbe garden; here Beyazit II lies buried in a simple, well-proportioned türbe of limestone picked out in verd antique. Nearby is the even simpler türbe of his daughter, Selçuk Hatun. Beyond these, a third türbe in a highly decorated

Empire

style is that of the Grand Vezir Koca Re

ş

it Pa

ş

a, the distinguished leader of the Tanzimat (Reform) movement, who died in 1857. Below the eastern side of the türbe garden facing the street is an arcade of shops originally erected by Sinan in 1580; it had long since almost completely disappeared, but one of the happier ideas in the redesigning of Beyazit Square was to reconstruct it.

Just beside these shops is the large double sibyan mektebi with two domes and a porch; this is undoubtedly the oldest surviving primary school in the city, since that belonging to the külliye of Fatih Mehmet has disappeared. It has recently been handsomely restored and now houses the hakk

ı

tar

ı

k us Research Library. (hakk

ı

tar

ı

k us was a journalist who, like the poet e.e. cummings, had an aversion to capital letters.) Between this building and the northern minaret is a very pretty courtyard called the Sahaflar Çar

ş

ı

s

ı

, or the Market of the Secondhand Book Sellers, in which we will linger on our next stroll through the city.