Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City (20 page)

Read Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City Online

Authors: Hilary Sumner-Boyd,John Freely

Tags: #Travel, #Maps & Road Atlases, #Middle East, #General, #Reference

We now leave the At Meydan

ı

by the street at the south-western end, walking alongside the building there, now the Rectorate of Marmara University. At the first turning we pass through a gate and enter the garden behind the school (the gateman never objects to visitors). This garden occupies part of the

sphendone

, the southern, semicircular end of the Hippodrome. The chief reason for coming here is the view, which is very fine. The Marmara coast of the city can be seen in all its extent, from Saray Point to the Marble Tower, where the land walls meet the Marmara. Looking out across the Marmara we see the Princes’ Isles floating between sea and sky, and beyond them the mountains of Asia; on a clear day we can see the Bithynian Olympus (Uluda

ğ

) with its snow- capped summit. In the foreground just below us to the right is the mosque of Sokollu Mehmet Pa

ş

a, and straight ahead by the seashore the former church of SS. Sergius and Bacchus with its curiously corrugated dome; these are the next important items on our itinerary. If we look down over the railing, we see the great supporting wall of the Hippodrome. Within this wall, under our feet, are various stone chambers and the long spacious corridor which ran round the whole length of the Hippodrome and from which doors and staircases led to the various blocks of seats. Part of this corridor was converted into a cistern in later Byzantine times and still supplies water to the district below. If we look back in this direction from the seashore beyond SS. Sergius and Bacchus, we will see the whole sweep of the great semicircular wall.

We now return to the street outside and follow it downhill to the second turning on the left, where at the corner we see the remains of an ancient mosque. This is Helvac

ı

Camii, founded in 1546 by one Iskender A

ğ

a: it is too ruinous to be of any interest. Farther down the street to the left is a very odd and interesting tekke, or dervish monastery. This is part of the külliye of Sokollu Mehmet Pa

ş

a Camii built by the great Sinan, which is just below it. It is rather oddly designed, but its form is unique because of the steep descent of the hill on which it is built. We enter by a little domed gatehouse and find immediately opposite the large and handsome mescit-zaviye, or room for the dervish ceremonies. On the right is a small porticoed courtyard with the cells of the dervishes; on the left is another courtyard of cells, but in this case it is in two storeys because of the difference in level: one descends to the lower level by a staircase behind the zaviye

.

Both courtyards are rather low and dark with square pillars instead of columns, which give them a somewhat forbidding appearance; but the arrangement as a whole is ingenious and attractive. The building has recently been rather summarily restored.

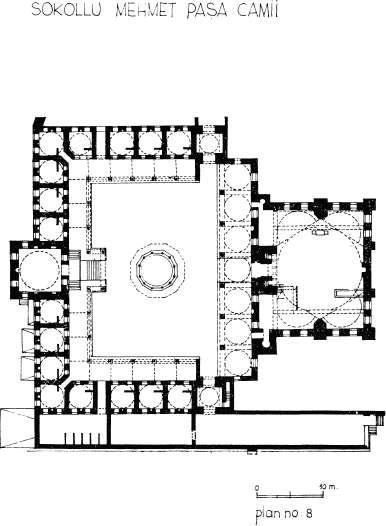

We now return to the street from which we branched off and continue down to the left; presently a gate leads to the garden and courtyard of a great mosque. This is one of the most beautiful of the smaller mosques of Sinan. It was built in A.H. 979 (A.D. 1571–2) for Ismihan Sultan, daughter of Selim II and wife of the Grand Vezir Sokollu Mehmet Pa

ş

a after whom the mosque is generally called. This mosque is built on the site of an ancient church, once wrongly identified as that of St. Anastasia, from which doubtless the columns of the courtyard were taken.

The courtyard itself is enchanting in design. It served, as in the case of many mosques, as a medrese; the scholars lived in the little domed cubicles or cells under the portico. Each cell had its own window, its fireplace and its recess for books. Instruction was given in the dershane, the large domed room over the staircase in the west wall, and also in the mosque itself. Notice the charming ogive arches of the portico and the fine

ş

ad

ı

rvan in the centre. The porch of the mosque forms the fourth side of the court; in the lunettes of the window are some striking and elegant inscriptions in blue and white faience. Entering the building, one is delighted by the harmony of its lines, the lovely soft colour of the stone, the marble decoration and, above all, the tiles. In form, the mosque is a hexagon inscribed in a rectangle (almost square), and the whole is covered by a dome, counter-balanced at the corners by four small semidomes. There are no side aisles, but around three sides runs a low gallery supported on slender marble columns with the typical Ottoman lozenge capitals. The polychrome of the arches, the voussoirs of alternate green and white marble, is characteristic of the classic period.

The tile decoration in the mosque has been used with singularly charming effect. Not the entire wall but only selected areas have been sheathed in tiles: the pendentives of the dome, the exquisite mihrab section of the east wall, and a frieze of floral designs under the galleries. The predominant colour is a cool turquoise, and this has been picked up again here and there in the carpets. The whole effect is extraordinarily harmonious. Above the entrance portal can be seen a small specimen of the wonderful painted decoration of the classical period. It consists of very elaborate arabesque designs in rich and vivid colours. Also above the door, surrounded by a design in gold, is a fragment of black stone from the holy Kaaba in Mecca; other fragments can be seen in the mihrab and mimber, themselves fine work in carved marble and faience.

We leave the mosque by the broad staircase below the west wall of the courtyard (notice the fine inlaid arabesque woodwork of the great doors), and turn left and then right onto Kadirga Liman Caddesi. This picturesque old street soon brings us to a large open square, much of which is now used as a playground. This is the pleasant area known as Kadirga Liman

ı

, which means literally the Galley Port. As its name suggests, this was anciently a seaport, now long since silted up and built over. The port was originally dug and put in shape by the Emperor Julian the Apostate in 362 and called after him. In about 570, Justin II redredged and enlarged it and named it for his wife, Sophia. It had continually to be redredged but remained in use until after the Turkish Conquest. By about 1550, when Gyllius saw it, only a small part of the harbour remained and now even this is gone. Today only bits and pieces of the inner fortifications of the harbour are left, cropping up here and there as parts of houses and garden walls in several of the streets between here and the sea

.

In the centre of the square, Kadirga Liman Meydan

ı

, there is a very striking and unique monument. This is the namazgah of Esma Sultan, daughter of Ahmet III, which was built in 1779. It is a great rectangular block of masonry, on the two faces of which are fountains with ornamental inscriptions, the corners having ornamental niches, while the third side is occupied by a staircase which leads to the flat roof. This is the only surviving example in Stamboul of a namazgah, or open-air place of prayer, in which the k

ı

ble or direction of prayer is indicated but which is otherwise without furniture or decoration. Namazgahs are common enough in Anatolia and the remains of at least two others can be seen in the environs of Istanbul, one in the Okmeydan

ı

overlooking the Golden Horn and the other at Anadolu Hisar

ı

on the Bosphorus; but this is the only one left in the old city.

After leaving the namazgah, we cross to the street at the southern side of the park and turn left. This street soon brings us to a large open field, Cinci Meydan

ı

, which is bordered on the side by the railroad line. Cinci Meydan

ı

, the Square of the Genii, is named after Cinci Hoca, a favourite of Sultan Ibrahim, who once owned land on this site. When Ibrahim first came to the throne there was some doubt as to his sexual potency, and so his mother Kösem sought out Cinci Hoca, who had acquired a considerable reputation as a

büyücü

, that is, a wizard quacksalver. Cinci Hoca would seem to have done his job well, for Ibrahim soon had the Harem swinging with cradles and was performing sexual spectaculars which are still recalled with awe. But when Crazy Ibrahim was deposed in 1648, Cinci Hoca fell too, and he and his friend Pezevenk (the Pimp) were torn to pieces by an angry mob in the At Meydan

ı

. The Square of the Genii is today a football field, which we pass and continue eastward, following a narrow lane parallel to the railroad track.

SS. SERG

İ

US AND BACCHUS

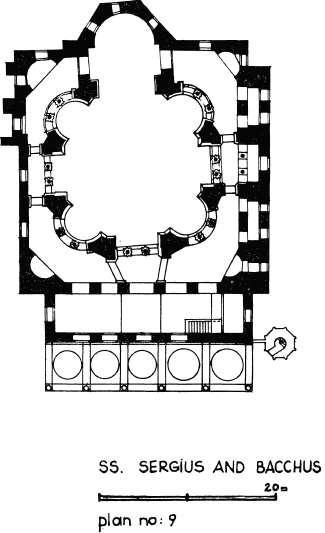

At the end of this lane, we come to one of the entrances to the courtyard of the beautiful Küçük Aya Sofya Camii, the former Byzantine church of SS. Sergius and Bacchus. The church was begun by Justinian and his Empress Theodora in 527, five years before the commencement of the present church of Haghia Sophia. It thus belongs to that extraordinary period of prolific and fruitful experiment in architectural forms which produced, in this city, buildings so ambitious and so different as the present church, Haghia Sophia itself, and Haghia Eirene – to name only the existing monuments – and in Ravenna, St. Vitale, the Baptistry and St. Apollinare in Classe. It is as if the architects were searching for new modes of expression suitable to a new age. The domes of this period are specially worthy of note: the great dome of Haghia Sophia is of course unique, but the method of transition from the octagon to the dome here is astonishing: the dome is divided into 16 compartments, eight flat sections alternating with eight concave ones above the angles of the octagon. This gives the dome the oddly undulatory or corrugated effect we noticed when looking down on it from the

sphendone.

The octagon has eight polygonal piers between which are pairs of columns, alternately of verd antique and red Synnada marble both above and below, arranged straight on the axes but curved out into the exedrae at each corner. The whole forms an arcade that gives an effect almost of choric dancers in some elaborate but formal evolution, as Procopius happily says in another connection. The space between this brightly coloured, moving curtain of columns and the exterior walls of the rectangle becomes an ambulatory below and a spacious gallery above. (One ascends to the gallery by a staircase at the south end of the narthex; don’t fail to do so, for the view of the church from above is very impressive.) The capitals and the classic entablature are exquisite specimens of the elaborately carved and deeply undercut style of the sixth century. On the ground floor the capitals are of the “melon” type, in the gallery “pseudo-Ionic”, and a few of them still bear the monogram of Justinian and Theodora, though most of these have been effaced. In the gallery the epistyle is arcaded in a way that became habitual in later Byzantine architecture – already in Haghia Sophia, for example; but on the ground floor the entablature is still basically classical, trabeated instead of arched, with the traditional architrave, frieze, and cornice, but how different in effect from anything classical: like lace. The frieze consists of a long and beautifully carved inscription in 12 Greek hexameters in honour of the founders and of St. Sergius; oddly enough St. Bacchus is not mentioned. SS. Sergius and Bacchus were two Roman soldiers martyred for their espousal of Christianity; later they became the patron saints of Christians in the Roman army. These saints were especially dear to Justinian because they saved his life some years before he came to the throne, in the reign of Anastasius. It seems that Justinian had been accused of plotting against the Emperor and was in danger of being executed, but Sergius and Bacchus appeared in a dream to Anastasius and interceded for him. As soon as Justinian himself became Emperor in 527, he expressed his gratitude to the saints by dedicating to them this church, the first of those with which he adorned the city.