Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City (38 page)

Read Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City Online

Authors: Hilary Sumner-Boyd,John Freely

Tags: #Travel, #Maps & Road Atlases, #Middle East, #General, #Reference

of the Conqueror

Where one stroll ends another must begin, if we are to see Istanbul in all its detail. And so we return to the south-west corner of the traffic-circle at

Ş

ehzadeba

ş

ı

, to begin our next tour of the city. Once there, we will begin walking westward along the south side of

Ş

ehzadeba

ş

ı

Caddesi. This will bring us into the district called Fatih, named after Fatih Camii, the Mosque of the Conqueror, around which we will be strolling.

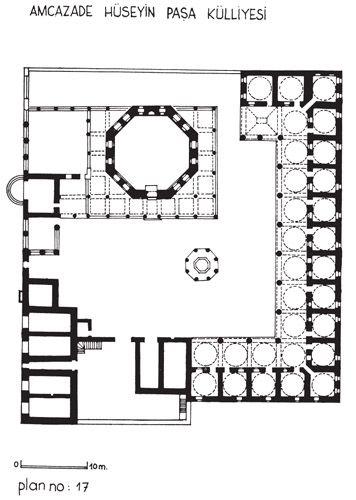

THE AMCAZADE COMPLEX

Just to the west of the ruins of the church of St. Polyeuktos, which we examined on our last tour, we come to the fine complex of Amcazade Hüseyin Pa

ş

a. This is one of the most elaborate and picturesque of the smaller classical complexes. It was built by Hüseyin Pa

ş

a while he was Grand Vezir (1697–1702) under Mustafa II, and thus comes at the very end of the classical period. Hüseyin Pa

ş

a was a cousin

(amcazade)

of Faz

ı

l Ahmet Pa

ş

a of the able and distinguished Köprülü family. The historian von Hammer says of him: “He was the fourth Köprülü endowed with the highest authority of the Empire and like his relatives he showed himself capable of supporting its weight... After his uncle Mehmet Köprülü the Cruel and his cousins Ahmet the Statist and Mustafa the Virtuous, he well-deserved the surname of the Wise. Unfortunately he remained too short a time on the stage where his high qualities had placed him, fully capable as he was of retarding if not altogether forestalling the decadence of the Empire, from which he disappeared like a meteor after having given rise to the highest hopes.”

The complex includes an octagonal dershane or lecture hall, serving also as a mosque; a medrese, a library, a large primary school over a row of shops, two little cemeteries with open türbes, a

ş

ad

ı

rvan, a sebil and a çe

ş

me, all arranged with an almost romantic disorder. The street façade consists first of the open walls of the small graveyards, divided by the projecting curve of the sebil. All of these have fine brass grilles, those of the türbe nearest the entrance gate being quite exceptionally beautiful specimens of seventeenth-century grillework. Next comes the entrance gate with an Arabic inscription giving the date 1698. The çe

ş

me just beyond it with its reservoir behind is a somewhat later addition, for its inscription records that it was a benefaction of the

Ş

eyh-ül Islam Mustafa Efendi in 1739. Finally there is a row of four shops with an entrance between them leading to the two large rooms of the mektep on the upper floor. On entering the courtyard, one has on the left the first of the open türbes – the one with the exceptionally handsome grilles – and then the columned portico of the mosque: this portico runs around seven of the eight sides of the mosque and frames it in a rectangle. The mosque itself is without a minaret and its primary object was clearly to serve as a lecture hall for the medrese. It is severely simple, its dome adorned only with some rather pale stencilled designs probably later than the building itself.

The far side of the courtyard is formed by the 17 cells of the medrese with their domed and columned portico. Occupying the main part of the right-hand side is the library building. It is in two storeys, but the lower floor serves chiefly as a water reservoir, the upper being reached by a flight of outside steps around the side and back of the building, leading to a little domed entrance porch on the first floor. The medallion inscription on the front of the library records a restoration in 1755 by Hüseyin Pa

ş

a’s daughter after the earthquake of 1894 which ruined the complex; the manuscripts it had contained were removed and are now in the Süleymaniye library. The right-hand corner of the courtyard is occupied by the shops and the mektep above them: note the amusing little dovecotes in the form of miniature mosques on the façade overlooking the entrance gate. A columned

ş

ad

ı

rvan stands in the middle of the courtyard. This charmingly irregular complex is made still more picturesque by the warm red of the brickwork alternating with buff-coloured limestone, by the many marble columns of the portico, and not least by the fine old trees – cypresses, locusts and two enormous terebinths – that grow out of the open türbes and in the courtyard. The külliye now serves as the Museum of Turkish Architectural Works and Construction Elements, including architectural and sculptural fragments, calligraphical inscriptions and old tombstones. One particularly interesting exhibit is the top of one of the minarets of Fatih Camii, toppled by the earthquake in 1894.

DÜLGERZADE CAM

İ

İ

Opposite the Amcazade complex in a pretty little park is an ugly broken-off column, typical of First World War memorials everywhere; it commemorates Turkish aviators killed during the war and is dated 1922. On the north side of the park is the old Fatih Town Hall, built in 1913 in a style known as Ottoman Revivalism. Continuing westward along the main avenue on the same side as the Amcazade complex we pass an ancient but not very interesting little mosque called Dülgerzade Camii; it was built by one of Fatih’s officials,

Ş

emsettin Habib Efendi, sometime before his death in 1482.

COLUMN OF MARC

İ

AN

Beyond the mosque we turn left and a short distance down the street we see the second of the four late Roman honorific columns in the city, the Column of Marcian. This column, though known to Evliya, escaped even the penetrating eyes of Gyllius and remained unknown to the West until rediscovered in 1675 by Spon and Wheeler. It continued to be hidden away in a garden behind the houses around it until 1908, when a fire destroyed all the buildings and exposed it to view, and since then it has formed the centre of a little square. It is a monolithic column of Syenitic granite resting on a high marble pedestal; the column is surmounted by a battered Corinthian capital and a plinth with eagles at the corners on which there once must have stood a statue of the Emperor Marcian (r. 450–7). Fragments of sculpture remain on the base, including a Nike, or Winged Victory, in high relief. There is also on the base an elegaic couplet in Latin which says that the column was erected by the prefect Tatianus in honour of the Emperor Marcian. The Turks call the column K

ı

z Ta

ş

ı

, or the Maiden’s Column, because of the figure of the Nike on the base. Evliya Çelebi believed the Nike to be the figure of a Byzantine princess, daughter of an apocryphal ruler named King Puzantine (a corruption of Byzantine), and he claimed that the Maiden’s Column had talismanic powers: “At the head of the Saddler’s Bazaar, on the summit of a column stretching to the skies, there is a chest of white marble in which the unlucky-starred daughter of King Puzantine lies buried; and to preserve her remains from ants and insects was this column made a talisman.”

MEDRESE OF FEYZULLAH EFENDI

We now return to the main avenue and continue walking westward on the same side. We soon come to another little külliye built at about the same time as the Amcazade complex; this one is almost as charming though not as extensive. This is the medrese founded in 1700 by the

Ş

eyh-ül Islam Feyzullah Efendi; it now serves as the Millet Kütüphanesi, or People’s Library. The cells of the medrese surround two sides of the courtyard in which stands a

ş

ad

ı

rvan in the midst of a pretty garden. The street side of the courtyard is wholly occupied by a most elaborate and original dershane building: a flight of steps leads up to a sort of porch covered by nine domes of different patterns, the arches of which are supported on four columns. The effect of this porch has been somewhat impaired by glazing in a part of it, but its usefulness has doubtless been increased. To right and left of the porch are the large domed lecture-rooms, now used as library reading-rooms. The medrese, long disaffected and ruinous, was restored and converted into a library by Ali Emiri Efendi, a famous bibliophile who died in 1924 and left the building and his valuable collection of books and manuscripts to the people of Istanbul. The reading-rooms are almost always full of students.

COMPLEX OF FAT

İ

H SULTAN MEHMET

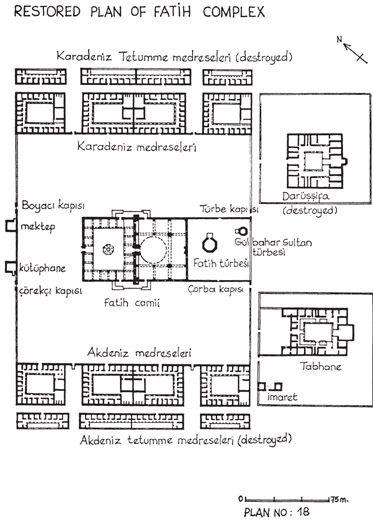

We now find ourselves opposite the enormous mosque complex of Mehmet the Conqueror. Let us continue past it along the avenue for a few hundred metres and then turn right on the first through-street, so as to approach the mosque from the western side of the great outer courtyard. The huge mosque complex built by Sultan Mehmet the Conqueror was the most extensive and elaborate in Istanbul, and indeed in the whole of the Ottoman Empire. In addition to the great mosque with its beautiful courtyard and its graveyard with türbes, the küllliye consisted of eight medreses and their annexes, a tabhane or hospice, a huge imaret, a hospital, a kervansaray a primary school, a library and a hamam. It was laid out over a vast, almost square area – about 325 metres on a side – with almost rigid symmetry, and Evliya Çelebi says of it: “When all these buildings, crowded together, are seen from a height above, they alone appear like a town full of lead-covered domes.” It occupies approximately the site of the famous Church of the Holy Apostles and its attendant buildings. This church, which was already partially in ruins at the time of the Conquest, was used as a source of building materials for the construction of Fatih’s külliye.

The complex is thought to have been built by Sinan the Elder between 1463 and 1470; the dates are given in the great inscription over the entrance portal. There is much controversy but almost no knowledge about who this architect was. He has various sobriquets: Atik, the Elder; Azatl

ı

, the Freedman; or (by Evliya) Abdal, the Holy Idiot. The second of these names suggests that he could not have been a Turk; on the other hand, his identification with an otherwise unknown Byzantine architect named Christodoulos, which is generally accepted by western writers, rests only on the late and suspect authority of Prince Demetrius Cantemir. If he was indeed a Greek, however, he could not possibly have been a “Byzantine architect”: one cannot for a moment believe that, in the fifteenth century, there was any Byzantine architect capable of building a dome 26 metres in diameter. He must have been a Greek boy from the European provinces of the Empire taken up in a

dev

ş

irme

(annual levy of youths) and trained in an Ottoman school of architecture. His gravestone is extant in the garden of the little mosque he built as his own

vak

ı

f

, or pious foundation, Kumrulu Mescidi (see Chapter 13). But from this we learn only that he was an architect – no mention of the Fatih complex – and, curiously enough, that he was executed in the year after it was completed, 1471. In this connection it is interesting to note the curious tale told by Evliya Çelebi in the

Seyahatname

, in which he says that Fatih ordered both the architect’s hands cut off, on the grounds that his mosque did not have as great a height as Haghia Sophia.

Let us now return to the mosque itself. The original mosque built by Atik Sinan was destroyed in the great earthquake of 22 May 1766. Mustafa II immediately undertook its reconstruction and the present building, on a wholly different plan, was completed in 1771. What remains of the original complex is most probably the courtyard, the main entrance portal, the mihrab, the minarets up to the first

ş

erefe, the south wall of the graveyard and the adjoining gate; all the other buildings of the complex were badly damaged but were restored presumably in their original form. What was the original form of the mosque itself? It is of course of the greatest interest and importance to know the original plan, for this was the first large imperial building to be erected after the Conquest. It appears, then, that the mosque had a very large central dome, 26 metres in diameter; that it was supported on the east only by a semidome of the same diameter; that these were supported by two great rectangular piers on the east and by two enormous porphyry columns towards the west, the latter supporting a double arcade below the tympanum walls of the great dome arches; to north and south were side aisles each covered with three small domes. The plan is very similar, on an enormous scale, to that of Atik Ali Pa

ş

a Camii at Çemberlita

ş

, and even more so to that of the Selimiye at Konya, which has been shown to be a small replica of it. This plan was in certain respects a natural development of previous Ottoman buildings. Nevertheless, those who saw and described this mosque before it was destroyed, foreigners and Turks alike, including Sultan Mehmet and his architect, compared Fatih Camii to Haghia Sophia; hence it must already have shown the overpowering influence of the Great Church.