Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City (60 page)

Read Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City Online

Authors: Hilary Sumner-Boyd,John Freely

Tags: #Travel, #Maps & Road Atlases, #Middle East, #General, #Reference

the Princes’ Islands

Visitors to Istanbul sometimes forget that an important part of the city is located in another continent, across the way in Asia. The most interesting of these Anatolian suburbs from the point of view of historical monuments is Üsküdar, which lies directly opposite the mouth of the Golden Horn.

Üsküdar was anciently known as Chrysopolis, the City of Gold, founded by the Athenians under Alcibiades in 409 B.C. Chrysopolis was in antiquity a suburb of the neighbouring and more important town of Chalcedon, the modern Kad

ı

köy, now itself a suburb of the great city across the strait. According to tradition, Chalcedon was founded in about 687 B.C., two decades before the original settlement of Byzantium. Chrysopolis, because of its fine natural harbour and its strategic location at the head of the strait, began to develop rapidly and later surpassed Chalcedon in size and importance. Chrysopolis became the starting place for the great Roman roads which led from Byzantium into Asia and was a convenient jumping-off place for military and commercial expeditions into Anatolia. Throughout the Byzantine period it was a suburb of Constantinople and thus had much the same history as the capital. Its site was not well-suited for defence, however, and it was on several occasions occupied and destroyed by invading armies while Constantinople remained safe behind its great walls. For this reason there are no monuments from the Byzantine period remaining there. The town was taken by the Turks in the middle of the fourteenth century, more than 100 years before the fall of Constantinople. (The Byzantine name Scutari, of which the modern Turkish Üsküdar is merely a corruption, dates from the twelfth century and derives from the imperial palace of Scutarion, which was at the point of land near Leander’s Tower. This has vanished, as have all other traces of Byzantine Chrysopolis.)

During the Ottoman Empire several members of the royal family, particularly the Sultan Valides, adorned Üsküdar with splendid mosques and pious foundations, most of which are still to be seen there today. Many great and wealthy Osmanl

ı

s built their mosques, palaces and konaks there too, preferring the quieter and more serene environment of Üsküdar to the tumult of Stamboul. Time was, and not so long ago either, when Üsküdar had a charmingly rustic and rural atmosphere reminiscent of Ottoman days. Traces of this still remain, although modern progress is fast destroying old Üsküdar, as it is so much else in this lovely city.

We can reach Üsküdar either by passenger ferry from the Galata Bridge or by the smaller boats from Kabata

ş

on the European shore of the lower Bosphorus. Either way we land at the iskele beside Iskele Meydan

ı

, the great seaside square of Üsküdar, much of which occupies the site of the ancient harbour of Chrysopolis. In Ottoman days it was known as the Square of the Falconers and was the rallying place for the Sürre-i-Hümayun, the Sacred Caravan that departed for Mecca and Medina each year with its long train of pilgrims and its sacred white camel bearing gifts from the Sultan to the

Ş

erif of Mecca.

ISKELE CAM

İ

İ

The ferry-landing is dominated on the left by a stately mosque on a high terrace; it takes its name, Iskele Camii, from the ferry-landing itself. The mosque was built in 1547–8 by Sinan for Mihrimah Sultan, daughter of Süleyman the Magnificent and wife of the Grand Vezir Rüstem Pa

ş

a. The exterior is very imposing because of its dominant position high above the square and its great double porch, a curious projection from which covers a charming fountain. The interior is perhaps less satisfactory, for the central dome is supported by three instead of the usual two or four semidomes; this gives a rather truncated appearance which is not improved by the universal gloom. Perhaps it was the gloominess of this building which made Mihrimah insist on floods of light when, much later, she got Sinan to build her another mosque at the Edirne Gate. Of the other buildings of the külliye the medrese is to the north, a pretty building of the rectangular type, now used as a clinic; the primary school is behind the mosque built on sharply rising ground so that it has very picturesque supporting arches; it is now a children’s library. On leaving the mosque terrace one finds at the foot of the steps the very handsome baroque fountain of Ahmet III, dated 1726.

Passing the fountain and entering the main street of Üsküdar we soon come on the left to a supermarket housed in the remains of an ancient hamam. The owner calls it Sinan Hamam Çar

ş

ı

s

ı

, thus ascribing the bath to Sinan; this is probably not so though it certainly belongs to his time. It was a double hamam, but the main entrance chambers were destroyed when the street was widened.

A little farther on is an ancient and curious mosque built by Ni

ş

anc

ı

Kara Davut Pa

ş

a towards the end of the fifteenth century. It is a broad, shallow room divided into three sections by arches, each section having a dome, an arrangement unique in Istanbul.

YEN

İ

VAL

İ

DE CAM

İ

İ

Across the street and opening into the square is the large complex of Yeni Valide Camii, built between 1708 and 1710 by Ahmet III and dedicated to his mother the Valide Rabia Gülnü

ş

Ümmetullah. At the corner is the Valides charming open türbe like a large aviary, and next to it a grand sebil. On entering by the gate from the square one sees a very attractive wooden façade, a later addition, which is the entrance to the imperial loge. The mosque itself is in the classical style at its very last gasp and before the baroque influence had come to liven it up; it is a variation of the octagon-in-square theme; the tiles are late and insipid. Walking through the outer courtyard one comes to the main gate, over which is the mektep, and outside the gate stands the large imaret with a later, fully baroque, çe

ş

me at the corner.

Taking the street opposite the main gate and turning left, then right, one reaches the precincts of one of Sinan’s most delightful smaller külliyes, that of

Ş

emsi Pa

ş

a, which attracts the attention as one approaches Üsküdar by boat because of its picturesqueness and the whiteness of its stone, just at the water’s edge. Built by Sinan for the Vezir

Ş

emsi Pa

ş

a in 1580, the mosque is of the simplest type: a square room covered by a dome with conches as squinches.

Ş

emsi’s türbe opens into the mosque itself, from which it is divided merely by a green grille, a most unusual and pretty feature. The well proportioned medrese forms two sides of the courtyard, while the third side consists of a wall with grilled windows opening directly onto the quay and the Bosphorus. The külliye has been beautifully restored in recent years.

The walk along this quay to the south is very pleasant and brings one in a short time to an ancient mosque halfway up a low hill to the left. This is the mosque of Rum Mehmet Pa

ş

a, built in 1471. In its present state, part of it badly restored, it is not a very attractive building, but it has some interesting and unusual features. Of all the early mosques it is the most Byzantine in external appearance: the high cylindrical drum of the dome; the exterior cornice following the curve of the round-arched windows; the square dome base broken by the projection of the great dome arches; and several other features suggest a strong Byzantine influence, perhaps connected with the fact that Mehmet Pa

ş

a was a Greek who became one of Fatih’s vezirs. Internally the mosque has a central dome with smooth pendentives and one semidome to the east like Atik Ali Pa

ş

a Camii, but here the side chambers are completely cut off from the central area. Behind the mosque is Mehmet Pa

ş

a’s gaunt türbe.

AYAZMA CAM

İ

İ

If one leaves the mosque precinct by the back gate and follows the winding street outside, keeping firmly to the right, one comes before long to an imposing baroque mosque known as Ayazma Camii. Built in 1760–1 by Sultan Mustafa III and dedicated to his mother, the Valide Sultan Mihri

ş

ah Emine, it is one of the more successful of the baroque mosques, especially on the exterior. A handsome entrance portal opens onto a courtyard from which a pretty flight of semicircular steps leads up to the mosque porch; on the left is a large cistern and beyond an elaborate two-storeyed colonnade gives access to the imperial loge. The upper structure is also diversified with little domes and turrets, and many windows give light to the interior. The interior, as generally in baroque mosques, is less successful, though the grey marble gallery along the entrance wall, supported by slender columns, is effective.

Leaving by the south gate and following the street to the east, one comes to a wider street, Do

ğ

anc

ı

lar Caddesi, with two pretty baroque çe

ş

mes at the intersection; turning right one finds at the end of this street a severely plain türbe built by Sinan for Hac

ı

Mehmet Pa

ş

a, who died in 1559. It stands on an octagonal terrace bristling with tombstones and overshadowed by a dying terebinth tree.

AHMED

İ

YE COMPLEX

The wide street just ahead leads downhill past a little park; the third turning on the right followed immediately by one on the left leads to an elaborate and delightful külliye, the Ahmediye mosque and medrese. Built in 1722 by Eminzade Hac

ı

Ahmet Pa

ş

a, comptroller of the Arsenal under Ahmet III, it is perhaps the last ambitious building complex in the classical style, though verging towards the baroque. Roughly square in layout, it has the porticoes and cells of the medrese along two sides; the library, one entrance portal, and the mosque occupy a third side, while the fourth has the main gate complex with the dershane above and a graveyard alongside; but the whole plan is very irregular because of the alignment of streets and the rising ground. The dome of the little mosque is supported by scallop-shell squinches and has a finely carved marble mimber and kürsü. But the library and the dershane over the two gates are the most attractive features of the complex and show great ingenuity of design. The whole külliye ranks with those of Bayram Pa

ş

a and Amcazade Hüseyin Pa

ş

a as among the most charming and inventive in the city.

We leave the Ahmediye by the main gate at the south-east corner of the courtyard, where a stairway under the dershane takes us to the street below. A short, narrow street opposite the outer gate soon leads to a wider avenue, Topta

ş

ı

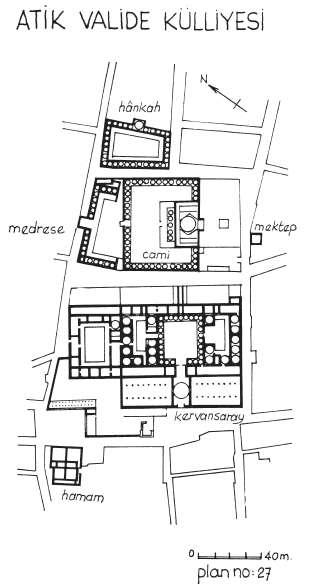

Caddesi, where we turn right. We follow this avenue for about 600 metres as it winds its way uphill. Then, towards the top of the hill and somewhat to the left we see the great mosque which dominates the skyline of Üsküdar, Atik Valide Camii.