Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City (63 page)

Read Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City Online

Authors: Hilary Sumner-Boyd,John Freely

Tags: #Travel, #Maps & Road Atlases, #Middle East, #General, #Reference

The island consists of two large hills separated in the middle by a broad valley, so that the road around it makes a figure eight. You can make the tour by fayton, the Büyük, or Grand Tour, going all the way round the island and the Küçük, or Short Tour, going around the northern half. From the road that crosses the island between the hills, foot paths lead up on either side to the monasteries which crown each. The Monastery of the Transfiguration on the north hill, Isa Tepesi, or the Hill of Christ, is in the depths of a pine forest. The original monastery is mentioned in the list compiled in 1159 by Manuel I Comnenus, and the first mention of it after the Conquest is in 1597; the katholikon of the present monastery is due to a complete rebuilding in 1869.

On the southern hill, Yiice Tepe, is the more famous monastery of St. George Koudonas; situated at almost the highest point of the island, 202 metres above the sea. According to tradition, the monastery was founded during the reign of Nicephorus II Phocas (r. 963–9), and it is mentioned in the list compiled in 1158 by Manuel I Comnenus. The present complex includes, besides the monastery itself, six separate churches and chapels on different levels, the older ones being on the lowest levels. The monastery celebrates the feast-day of St. George on 23 April, when many thousands of pilgrims make their way to the hilltop, some of them walking barefoot, tying talismans to the branches of the bushes and trees along the way. Many of them have lunch at the little outdoor restaurant beside the monastery drinking the rough red wine made by the monks, in a setting reminiscent of the Aegean isles.

The great block of monastic buildings on the western side has a pretty courtyard with galleries along one side; at the back it plunges dramatically into the valley below and looks from there like a fortress. From here one can look out across the sea to the remaining islands of the group. To the west is tiny Sedef Adas

ı

, the Island of the Pearl, known in Byzantium as Antherovitos. To the south we see the uninhabited little crag called Tav

ş

an Adas

ı

, Rabbit Island, known anciently as Neandros. Both of these islets once had their monasteries, of which now only a few scattered stones remain. A number of summer villas have in recent years been built on Sedef, but Neandros is inhabited only by sea-birds, who can be seen in their thouands perched on the cliffs on the southern end of the island.

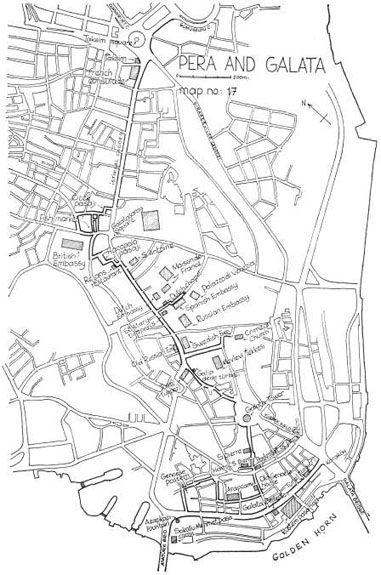

The historic origins of Pera and Galata are as remote in time as that of Constantinople itself.

From very early times there had been settlements and communities along the northern shores of the Golden Horn; Byzas himself is said to have erected a temple there to the hero Amphiaraus. The most important of these communities, Sykai, the Figtrees, where Galata now stands, was already in the fifth century A.D. included as the VIIIth Region, Regio Sycaena, of the city of Constantinople itself: it had churches, a forum, baths, a theatre, a harbour and a protecting wall. In 528 Justinian restored its theatre and wall and called it grandiloquently after himself Justinianae, a name which was soon forgotten. Towards the end of the same century, Tiberius II (r. 578–82) is said to have built a fortress to guard the entrance to the Golden Horn, from which a chain could be stretched to the opposite shore to close its mouth against enemy shipping; some substructures of this still exist at Yer Alt

ı

Camii near the Galata Bridge (see Chapter 21). The name, Sykai, continued in use until, in the ninth century, the name Galata began to supplant it, at first for a small district only, later for the whole region. The derivation of the name Galata is unknown, though that of the other apellation, Pera, is quite straightforward. In Greek

pera

means “beyond”, at first in the general sense of “on the other side of the Golden Horn”, later restricted to medieval Galata, and still later to the heights above. In the past generation these old Greek names have been supplanted by new Turkish ones; Pera is now known officially as Beyo

ğ

lu and Galata as Karaköy, but old residents of the town still refer to these quarters by their ancient names.

The town of Galata took its present form chiefly under the Genoese. After the reconquest of Constantinople from the Latins in 1261, the Byzantine emperors granted the district to the Genoese as a semi-independent colony with its own

podesta

or governor, appointed by the senate of Genoa. Although they were expressly forbidden to fortify the colony, they almost immediately did so and went on expanding its area and fortifications for more than 100 years. Sections of these walls with some towers and gates still exist and will be described later. After the Ottoman Conquest of 1453 the walls were partially destroyed and the district became the general European quarter of the city. Here the foreign merchants had their houses and their shops and here the ambassadors of the European powers built sumptuous embassies. For the rest, as Evliya Çelebi tells us, the inhabitants of Galata “are either sailors, merchants, or handicraftsmen, such as joiners and caulkers. They dress for the most part in the Algerine style, because a great number of them are Arabs and Moors. The Greeks keep the taverns; the Armenians are merchants and bankers; the Jews are negotiators in love matters and their youths are the worst of all the devotees of debauchery... The taverns are celebrated for the wine from Ancona, Sargossa, Mudanya, and Tenedos. When I passed through here, I saw many hundreds barefooted and bareheaded lying drunk in the streets.” Even now, there are evenings in the back streets of Beyo

ğ

lu when the scene is much the same as Evliya described it three centuries ago.

As time went on the confines of Galata became too narrow and crowded and the embassies and the richer merchants began to move out beyond the walls to the hills and vineyards above. Here the foreign powers built palatial mansions surrounded by gardens, all of them standing along the road which would later be known as the Grand Rue de Pera. Nevertheless, the region must have remained to a large extent rural till well on into the eighteenth century; in that period one often sees reference to “les vignes de Pera”. But as Pera became more and more built up, it fell a prey like the rest of the city to the endemic fires that ravage it periodically. Two especially devastating ones, in 1831 and 1871, destroyed nearly everything built before those dates. Hence the dearth of anything of much historic or architectural interest in Beyo

ğ

lu.

TAKS

İ

M SQUARE

Taksim Square is the centre of Beyo

ğ

lu and thus the hub of the modern town. The square takes its name from the taksim, or water-distribution centre, which is housed in the handsome octagonal structure at the south-west corner of the area; this was built in 1732 by Sultan Mahmut I, and is the collection-point for the water that is brought into the city from the reservoirs in the Belgrade Forest. The statue group in the centre of the square commemorates the founding of the Turkish Republic in 1923; this was done in 1928 by the Italian sculptor Canonica. At the north-east corner of the square is the Atatürk Cultural Centre, one of the principal sites for cultural events produced during the annual International Istanbul Festival. The avenue that leaves the square from its south-east corner is Gümü

ş

suyu Caddesi, which leads downhill to the Bosphorus at Dolmabahçe, passing on its right side the stolid edifice of the German Embassy. (We shall continue to call these great buildings embassies, though, since the removal of the capital to Ankara they are used largely as consulates only; for they are really too grandiose to be described as consulates.)

CUMHUR

İ

YET CADDES

İ

AND THE MODERN CITY

The northern side of Taksim Square is bordered by the Public Gardens, on whose western side runs Cumhuriyet Caddesi, the avenue that leads to the various quarters of the modern city. The first of these is Harbiye, where a branch of the avenue passes the Military Museum, housed in the old Military School. Arrayed outside the museum are a splendid collection of ancient cannon, most of them captured by the Turks during the days when the Ottoman armies swept victoriously through southern Europe and the Middle East. Inside the museum there is an extraordinary collection of arms and other military objects from both Europe and Islam ranging in date from the early Ottoman period up to modern times, as well as other objects of considerable historic interest. At the Military Museum there are also performances of military music by the famous Mehtar Band, dressed in Ottoman costumes and playing old Turkish instruments, a very stirring spectacle.

An avenue branching off Cumhuriyet Caddesi to the right brings one to the Spor ve Sergi Sarayi (the Sport and Exhibition Palace), the Aç

ı

k Hava Tiyatrosu (the Open-Air Theatre) and the Muhsin Ertu

ğ

rul

Ş

ehir Tiyatrosu (the City Theatre) which, together with the Opera House, form the centre of the city’s cultural life.

IST

İ

KLAL CADDES

İ

The avenue that leads off from the south-west corner of Taksim Square from the taksim itself is Istiklal Caddesi. This was formerly known as the Grand Rue de Pera, of which the Austrian historian Josef von Hammer once said: “It is as narrow as the comprehension of its inhabitants and as long as the tapeworm of their intrigues.” The avenue has now been conveted into a pedestrian mall. The old trolley line has been re-established, running the full length of the avenue between Taksim and Tünel, with a stop halfway along at Galatasaray Meydan

ı

.

Just beyond the taksim building and on the same side of the street is the old French Consulate (consulate, not embassy, which is farther on down the avenue); it is a building with a rather quaint courtyard originally constructed by the French in 1719 as a hospital for those suffering from the plague.

The streets leading off on either side from Istiklal Caddesi between Taksim and Galatasaray are lined with restaurants, cafés, bars and night clubs, for this district is the centre of Istanbul’s night life, which has tremendously expanded in recent years, attracting celebrants from all over the world. Many of the buildings along the avenue date from the last-half-century of the Ottoman era, such as the Tokatlian Han, Cercle d’Orient, Atlas Cinema and Cité Roumelie. Halfway between Taksim and Galatasaray we see on the right the only mosque on the avenue, A

ğ

a Camii. The first mosque on this site was founded in 1594–5 by Hüseyin A

ğ

a, commander of the Janissary detachment at Galatasaray; this was rebuilt in 1834 and restored in 1936.

After a ten or 15 minute stroll from Taksim we come to Galatasaray Meydan

ı

. The square takes its name from the Galatasaray Lisesi, whose ornate entrance we see on the left side of the avenue. Although the buildings of the lycée are modern (1908), Galatasaray is a venerable and distinguished institution. It was founded by Sultan Beyazit II around the end of the fifteenth century as a school for the imperial pages, anciliary to the one in Topkap

ı

Saray

ı

. The school was reorganized in 1868 under Sultan Abdül Aziz as a modern lycée on the French model, with the instruction partly Turkish, partly in French. It is the oldest Turkish institution of learning in the city with a more or less continuous history; and for the past 100 years it has been the best as well as the most famous of Turkish lycées. A large proportion of the statesmen and intellectuals of Turkey have pursued their studies there and it has undoubtedly played a major role in the modernization of the country. It now has a university as well, situated on the Bosphorus near Be

ş

ikta

ş

.