Sugar in My Bowl (18 page)

Authors: Erica Jong

Tags: #Health & Fitness, #Sexuality, #Literary Collections, #Essays

CONCLUSION

The best sex the subjects ever had is the sex they’re having next.

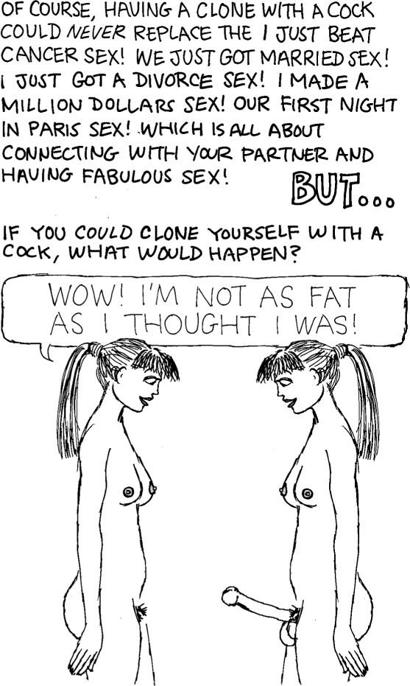

A Graphic Fantasy

Marisa Acocella Marchetto

A Satire

Susan Kinsolving

W

e were madly, multiculturally, in love. We were habitually, historically, in heat.

He was my Peking Man; I was his fire. He was my wheel; I was his box. He called me his Demeter, Earth Mother, Cybele, Isis, and Corn Goddess. I was silk; he was silage.

To my giggling Greek girl, he was a gigantic Gilgamesh. He was Casanova; I feigned Chastity. He was Incubus to my Succubus, Benedict to my Beatrice, an otolaryngologist to my Deep Throat.

Every night, he showed me more of his special collections: codpieces, chastity belts, Valentines, dildos, and pre-Columbian stirrup-spout vessels.

He read Homer aloud, explaining etymologies without apologies for: androgyny, aphrodisiac, eroticism, hermaphroditism, nymphomania, and satyriasis. He quoted from Ovid’s

Ars Amatoria,

the Kama Sutra,

Master Jung-ch’eng’s Principles, Thy Neighbor’s Wife, Couples, Fear of Flying,

and

Dog Breeding for Dummies

.

In the pink shell of my perfumed ear, he would whisper Sumerian songs asking “to put a hot fish in my naval.”

Never erring with Eros, he was my guy; I was his gyne. He was a boy in my brothel, a powerhouse to pudenda, a yang to yin. He followed the advice of Master Tung-hsüan, working his Jade Stalk and Gamboling Wild Horses to my Cinnabar Cleft and Hovering Butterflies. He was a master without Masters & Johnson; kinky without Kinsey.

He also performed as a troubadour and jongleur, creating his own court, where I was the unconsummated lady and he, the chivalrous crusader. He was Lancelot to my Guinevere. How he could polish armor, night after knight, I never knew.

Sometimes he had me wear a blood bandage. Other times, he celebrated ancient circumcision rites, but never made the cut. Marvelously, he masqueraded as the Marquis, without inflicting much misery. He also played a dashingly devilish Donald Duck to my besotted Betty Boop. On a weekly basis, he celebrated The Rites of Spring.

Romance and dogma, sacred and profane, concessions and caricatures, all those made him someone extraordinary. He was the best; eventually, I was bested.

Now only memory brings back that final night with a full moon, swelling sea, and his sudden, spectacular vasocongestion. We were in systolic acceleration. His Cowper’s gland opened, moistening and meeting my Bartholin’s. His face grimaced, toes curled, and feet arched. His skin flushed. My brain was swamped and seared with sensation, like a superabundant sneeze coming on. Then came that seismic shocker with extravagant pyrotechnics. His cries resembled an ecstatic orangutan, an animalistic outpouring, a big O of inhuman annunciation, wild whoops. I fell silent. And then, a sweat broke out, and it all was over. Over with a big O.

I can only wonder where he went, and what it all meant, when he left without a word. Instead of a note, I found a box of condoms. I am keeping it, a memento, for our love child, when he comes of age.

Min Jin Lee

I

n 1995 when I was twenty-six years old, I quit my job as a corporate lawyer to write fiction full- time. Less than a year later, I had a fat book manuscript with a lofty title and an agent willing to send it out. Around the same time, I also asked my husband to read it. By then, Christopher and I had been married for about three years, and one of the reasons I fell in love with him was that he was a very good reader. The fact that he read Kobo Abe, Julian Barnes, and Wallace Stegner had been as important to me as his engaging sense of humor.

It took him a while to finish, but when he finally did, I asked him to be truthful.

“I didn’t like your main character Annie. She’s dull and unsympathetic. And there’s no sex in the book.”

My normally calm husband was nervous, and he didn’t say anything more. If I didn’t want the man I loved and respected to say these things, it was clear that he didn’t enjoy saying them either. Within weeks, every major publisher had rejected my manuscript. I asked my agent to stop circulating it and buried the box of pages on the bottom shelf.

Over the years, as I worked on two other novel manuscripts and a passel of short stories, Christopher’s comments continued to buzz in my head, especially what he’d said about the lack of sex in the pages. Not every book needed to have sex in it, I argued with myself. That said, for most of my reading life, I’d been in thrall to late-nineteenth-century and early-twentieth-century classics with romantic plots and passionate heroines. The depictions of lovemaking in those books may seem quaint to the turn-of-the-twenty-first-century reader, but their sexual plots were outrageous for their respective times, even testing obscenity laws: Emma Bovary had a tryst in a horse-drawn carriage; George Eliot’s dairymaid Hetty Sorrel was deflowered in the woods by a country squire; governess Jane Eyre was engaged to her married, much older employer, Mr. Rochester; and Lady Chatterley and gamekeeper Mellors practiced buggery. If anything, the fine old books were a testament to the notion that sex was deeply relevant to the human condition and if nothing else, to timeless storytelling. Looking backward at my betters made me realize that I was shy at best, cowardly at most. Okay, I was terrified to write about sex.

I had my reasons.

During my junior year at Yale, I dated a white European graduate student who was nearly a decade older. Early on in this hazardous relationship, he took me to a friend’s party. In the modest kitchen of a grad student rental, the host’s wiry husband leaned against the wall, his narrow hip cocked. He looked at me then turned to ask my boyfriend my ethnicity. I was the guest of a guest, and I didn’t want to embarrass anyone, but as I stared at the boxes of white wine on the Formica table, I wondered why the guy wasn’t asking me. When my boyfriend answered Korean, the host’s husband opened his eyes wide in delight.

“Well, all right! You know Korean girls are wild in bed.”

This time, it wasn’t that I was afraid of looking foolish; I was just too stupid to say anything.

When the host’s husband left, my boyfriend explained that he was drunk. “Ignore it, okay?”

But I couldn’t. A few minutes later, I went to the bedroom to get my coat because I wanted to leave. The boyfriend could stay if he wanted to, but I’d had enough of him and the party. When I turned around to storm off, I found that the host’s husband had tailed me to the bedroom. Did I want to hook up with him? he asked. “What?” I declined and left.

Prior to the graduate student whom I dated and broke up with on a regular basis for the remainder of my college years, I’d had one serious relationship, with a boy from high school who after three years decided to go out with someone else. Before the grad student party, I had not known that Korean women were considered to be sexually wild or game enough to cheat on their boyfriends and hook up with married guys. It was 1988, and I was nineteen years old. Clearly, I needed to wise up.

Soon enough, other incidents followed, confirming that my Asian face and body were disproportionately sexualized without my say-so. When I walked down Chapel Street in New Haven, homeless white and black Vietnam veterans came up close, saying they wanted to fuck my gook cunt. The other expression used was slanty pussy. Once on a sunny spring afternoon, a homeless man touched the crotch of my baggy jeans. Ashamed and scared, I ran back to my dorm room and stayed there.

In high school, I had been an immigrant kid from Queens who took the subway on a three-hour round-trip to the Bronx each day. On weekends and summers, I worked at my parents’ wholesale jewelry shop. I taught Sunday school. Most of my waking life was spent on schoolwork or reading borrowed library books. In terms of appearances, I was an unnaturally tall Korean girl with small eyes behind thick eyeglasses. My mother gave me a bob cut every two months or so by the kitchen sink. The quiet second daughter of a strict Protestant minister, my lovely mother was never told that she was pretty, and she did the same when raising her three daughters. Vanity was shameful. The body was neither repudiated nor embraced. We just didn’t speak of it.

I wasn’t proud of this, but I didn’t know much about sex beyond my one high school boyfriend and the racy plots of hundred-year-old books. The cool girls in high school and college had elegantly knotted strings of lovers—diaries filled with notable passages. Was lovemaking beautiful and pleasurable? Sure, I believed that. Sex positive? Why not. Did I look or feel sexy? No, that would have been a stretch. So how had I become an unwitting and unqualified member of a tribe with a reputation?

I wanted some answers, so I signed up for classes in Women’s Studies and Asian-American History and Literature. Alas. In print and visual media Asian women were often hookers, mail-order brides, masseuses, porn stars, dragon ladies, submissive sex slaves, and yes, cartoon characters with long black hair, red lips, and racially improbable bosoms. Asian men were sinister gangsters, inscrutable businessmen, angry nerds, and scheming eunuchs. If Asian women were oversexual, then their brothers were asexual.

The allegedly positive model minority stereotype said Asian kids were good at math, and immigrant parents were hardworking machines. My mother had been a beloved piano teacher in Seoul, and in New York, she worked behind a dusty store counter alongside my father for almost two decades without complaining. As a dutiful Korean wife, she was the portrait of the stoic, unpaid female employee in the immigrant family business model.

There was also the less spoken of yet widely pervasive and condescending notion that an Asian woman was either a victimized sex worker (your family had sold you when you were eight to the highest bidder for your virgin price), or you were a docile sexual partner of a white male loser who could never get an attractive white woman (for an obedient wife, call 1-800-jadelily). If an Asian girl dated or married a white guy, the relationship was read as suspect and imbalanced—socially, romantically, and financially. If the Asian woman married some great white male, she was despised. (See Yoko Ono.)