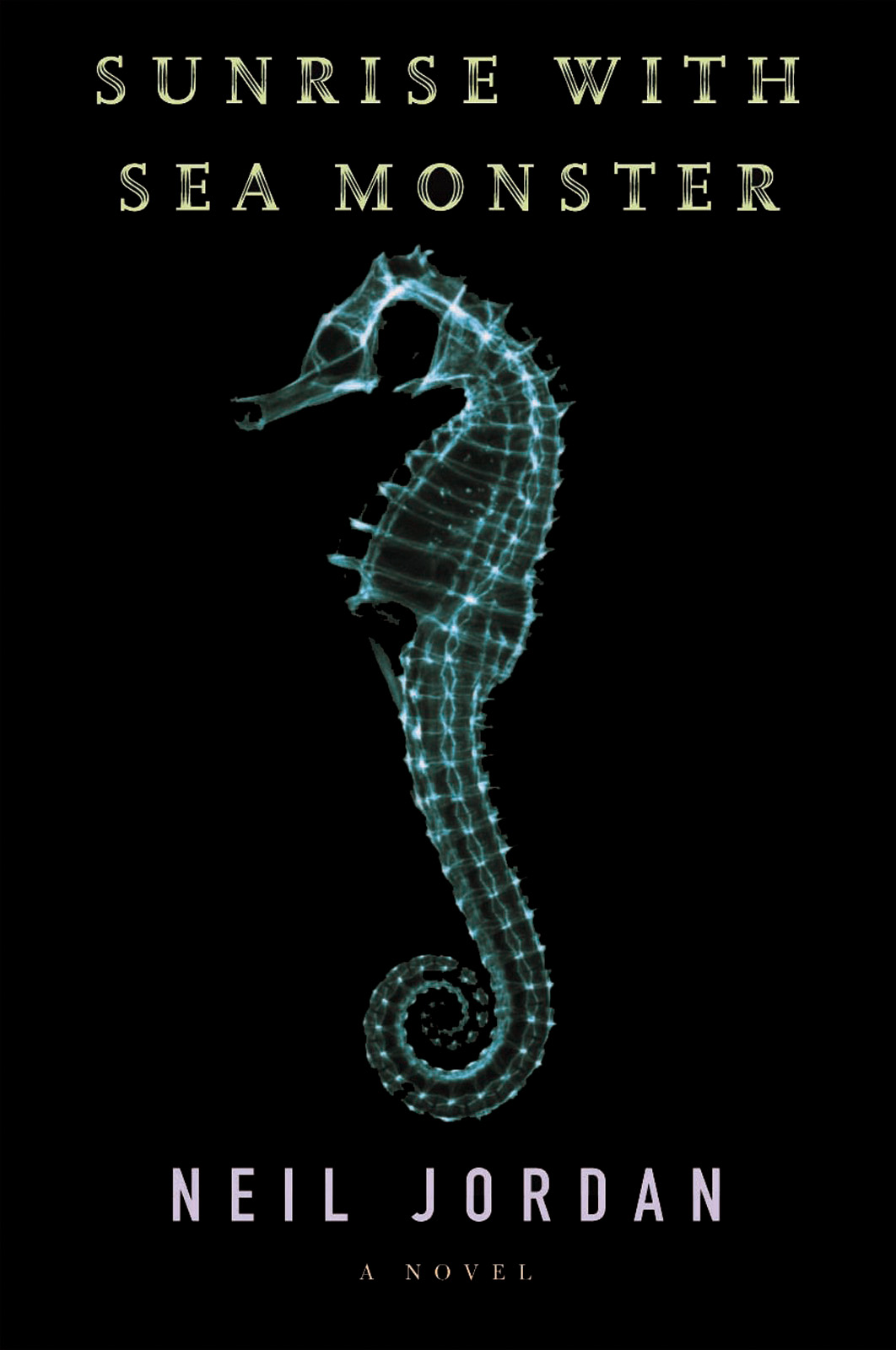

Sunrise with Sea Monster

Read Sunrise with Sea Monster Online

Authors: Neil Jordan

SUNRISE WITH SEA MONSTER

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Night in Tunisia

The Past

The Dream of a Beast

The Crying Game

(screenplay)

Shade

SUNRISE WITH

SEA MONSTER

A NOVEL

NEIL JORDAN

Copyright © 1994 by Neil Jordan

The lines quoted are by Emily Dickinson, Poem 712.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from

the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information address Bloomsbury

Publishing, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010.

Published by Bloomsbury Publishing, New York and London

Distributed to the trade by Holtzbrinck Publishers

First published in the United Kingdom in 1994 by Chatto & Windus Limited First published in the United States in 1995 by Random

House as

Nightlines

This Bloomsbury paperback edition published 2004

All papers used by Bloomsbury Publishing are natural, recyclable products made from wood grown in well-managed forests. The

manufacturing processes conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Jordan, Neil, 1951-

Sunrise with sea monster : a novel / Neil Jordan.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-1-59691-821-4

1. Spain—History—Civil War, 1936-1939—Prisoners and prisons—Fiction. 2. Triangles (Interpersonal relations)—Fiction. 3. Fathers

and Sons—Fiction. 4. Prisoners of war—Fiction. 5. Irish—Spain—Fiction. 6. Aging parents—Fiction. 7. Stepmothers—Fiction. 8.

Ireland—Fiction. I. Title.

PR6060.O6255S86 2004

823'.914—dc22

2004047659

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Typeset by Hewer Text Ltd, Edinburgh

Printed in the United States of America

by Quebecor World Fairfield

For Brenda

CONTENTS

I

RELAND WAS NEUTRAL during the Second World War, a policy that led to much that was sinister, much that was ridiculous. The

country had achieved independence from Britain, but at a cost. The War of Independence (1918—21) had led to a treaty with

Britain that was rejected by the more radical factions within the Irish Republican Army. These divisions led to a civil war,

where those for and against the treaty fought with a savagery that surpassed that of the War of Independence itself. Eamon

De Valera led the anti-treaty faction, Liam Cosgrave the pro-treaty government. Normal politics resumed when the Civil War

exhausted itself, and in 1932 Eamon De Valera won a majority and was elected Taoiseach (prime minister). He was to dominate

the politics of Ireland for the next forty years. His former comrades in the IRA who disagreed with any accommodation with

the treaty were then outlawed and suppressed. As the Second World War drew closer, the IRA itself split into factions that

mirrored the divisions in Europe. One faction supported the fight against fascism, particularly in Spain. The other regarded

England's enemy as its natural ally and was thus drawn into support for Nazi Germany.

De Valera pursued his policy of neutrality during the Second World War with extraordinary rigor, ruthlessly proscribing the

splintered remnants of the IRA, censoring the press, and effectively sealing off the Irish Republic from any contact with

events in Europe.

For further information, see the Glossary.

T

HEY FILE OUT with the first light and let us stand there for an hour or two. The light will change, we know, from dim silver

to a blinding white during our stasis and, for the few minutes of what they properly call dawn, the giant hoarding of the

Virgin will have a sky of ribboned magenta behind it. Almost a halo, of the quite conventional kind, which adorns as an afterthought

the hoarding of the Spaniard to her left and the Italian to her right. Though their shared glory will take some time to arrive.

Both Mussolini and Franco flap against their wooden supports in the wind the heatening sun drives before it, wearing similar

hats, painted with the same monumental rigidity, flicking with each thwack, as if mildly epileptic. She smiles in between,

moved only by the same occasional twitch, a sad smile on her face, a rigid smile, a monumental one but not too different really

from the smiles on the statues back home.

Behind her, on the wooden box-towers, the Moroccans stand, half-sleeping in their uniforms, one of them banging the nails

of the boards that hold him with his rifle-butt. He doesn't care for the light changing behind him, maybe because he has to

stand all day. I can imagine anything behind those monastery walls, but nothing that would generate a flicker of interest

from his eyes. We care, since we know that the nauseous riot of colour behind her is only there to signal the procession out

of the barred doors, the priest coming last behind his peasant altar-boys, their vestments grubby and white, barely concealing

their khaki uniforms.

The Spaniards to one side, feet swollen under knots of rags, resigned already to what they know will face them. The dark stains

on the monastery wall, twenty yards from the Virgin's left hand, catch the eye only in so far as every eye tries to avoid

them. The Jewish kid from Turin, his large eyes forever regretting whatever immoderation drove him here. And the rest of us

stand bound by a common tough thread. Not being our fight, it could well not be our execution, a thought that plays with a

sly unwitting smile behind each face, the way a child who hears of death for the first time can but laugh, then suppresses

it with the most appropriate demeanour. So we stand there, tough, resilient and apparently bored.

I remember my father, and what got me here. We would lay nightlines, in our rare moments of tranquillity, on the beach below

the terrace where our house was. Thin strings of gut between two metal rods strung intermittently with hooks, much like the

barbed wire that joins the box-towers, on one of which the Moroccan still bangs with his rifle-butt. We would jam them in

the hard sand at low tide; evening was always best, when all the water had retreated and the low light hit the ridges of the

scalloped sand. A mackerel sky behind us, more tranquil than the one now forming behind the Virgin's head. The lines pulled

taut, each hook neatly tied, his trousers rolled around his calfs, bare feet against the ridged sand. A shovel, and a rapid

succession of holes dug, around each ragworm cast. There were rags and lugs, I remember, the one all arms like a centipede,

the other like a bulbous eel, both adequate for the task in hand. Which was to walk back to where the lines were strung, shoes

in one hand, squirming mass of worms in the other, feet splaying sideways over the ridges of sand and skewer a worm on to

each waiting hook. By which time the sun was almost gone and the rags and lugs would swing gently squirming, dark against

the dying light. We would turn without a word after watching for a while as if words would have fractured the moment's—peace,

I would have said, but that would have implied a continuity of such moments between us, which there wasn't. Respite would

be truer, respite from the many gradations of awkward speech, and more awkward silences. Whatever the word, we both knew this

moment and would let nothing broach it, would walk back along the ribbed sand, my feet splayed to save them discomfort, his

firm, set flat across the scallops, bigger, harder, infinitely older. Shoes in one hand, shovel in the other.

The next morning there would be the catch of course, when the tide went out. A couple of plaice, a salmon bass, a dogfish,

swinging between the lines which would be bent with the weight, silver against the silver tide. We would walk out and could

talk now; I being the kid would run towards them, he being the father would identify each in that didactic way of his. I'd

walk towards him, my arms full of poles, wet fish and catgut. The reaping was never as rich as the sowing, somehow. I knew

that then and would connect that paradox with speech. The words, the sunlight, maybe the fact that the tide had come in. In

the house behind us she would already be being lifted from her bed for Sunday dinner. I'd deliver the fish to Maisie, who

lifted her, as she prepared the roast, and know they would be served and stay uneaten, at tea.

My memory of her is more uncertain, probably because she died before it could harden. The large bed which must have been theirs

before she fell ill, the rolls of toilet paper on the table to her left which her hand would make a handkerchief of when she

coughed and the mounds of discarded paper on the floor, which Maisie would clear up, periodically. I assume now we were only

let see her on her best days, which must have been infrequent. The bottles of perfume and quinine on the table, the smell

of that perfume, which reminded me of churches, and a harsher odour, something medicinal. There were pictures ranged about

the walls, of her with him, her with her numerous brothers, all with belts low and pot-bellies hanging over, hats at rakish

angles, cigarettes hanging from lips and fingers.

She would smile weakly when I came in and I would resist the urge to snuggle up beside her, stand by the bedstead playing

with the pearls she had draped round the metal, until her hand stretched over the pillow to grasp mine. Be a brave boy, Dony,

she'd say and draw me slowly down to the bed, where some infant urge would take me over and I'd reach across the mounds of

the quilt to clutch her shoulder and lie there, listening to both of us breathing. I would look from her face to the picture

of her in her wedding dress, smiling, holding a bouquet, veil slightly askew, then to the one of him in his IRA uniform. I

would ask her to tell me again the story of when the Tans came to catch him in the house near Mornington and she hid him among

the potato drills and beat them out of the house with a broomstick.

He was from the country, she was from the city, and the difference for some reason seemed to me significant, though I didn't

understand why. Her brothers would fill the house at weekends, ruffle my hair and press pennies in my hand and they spoke

with a wit and a freedom that seemed to have passed him by. He would spend hours with her in the room, the door closed to

any intrusion, nothing to indicate life inside but the low murmuring of their voices together. I would sit outside there,

pulling wool from the carpet and rolling it into balls, like some guardian of their privacy. Or I would take the opportunity

to wander through his office where the makeshift bed was that he slept in, the mass of papers on the green felt table by the

window, the inkpot and the fountain pen, the sheafs of government notepaper and in the drawer beneath it, when I found the

courage to open it, the gun in its leather shoulder-belt. It was significant in their union, I understood dimly, redolent

of a time and a series of events that united them, despite her illness, despite his accent and the fact that he slept in the

camp-bed by the corner. I would run my finger over its greasy surface and want to be beside her again, hearing her tell me

of the Black and Tans, the potato drills and the broomstick.

I was clearing nightlines with him when the end came. Both of us barefoot again as we jerked the fishes' gullets from the

hooks, whacked their heads on the hard sand, the white gills gasping and the cold blood streaming my fingers when I looked

up and saw Maisie on the promenade rubbing her hands in her smock with a distracted air and the doctor with the small black

bag, running. Wait here, my father said and he began to run too and I heard a strange cry from him as he ran, like an intake

of breath or the squawk of a herring-gull as he left me with the handfuls of half-dead fish. I knew the immensity of it because

he had left his shoes beside mine; it was most unlike that monument I thought my father was, scrambling over the layer of

pebbles between the sand and the promenade wall. The tide was way out, so far out it seemed impossible that the thin white

line by the horizon could have represented water. And it would be a dream I would have, many times later, the two of us walking

towards the lines we had placed the night before. The nightlines in the dream would be so far out it seemed impossible we

could have placed them but there, after all, they were, miles beyond the promenade wall, where the sand was sculpted in huge

soft curves and the fish our hooks had gleaned were not the comforting plaice and sole we were used to, but odd misshapen

creatures, pallid, translucent because of the depths they inhabited, huge whiskers and eyes, mouths shaped like tulips. We

would approach these fish with circumspection, so unexpected were they, but they were fish after all, could be torn from the

hooks and bleed like any others. And halfway through the work I would hear the roar, I would turn and see the white line of

the sea had become a wall, bearing down on us and we would run from this tidal wave dragging fish, irons and catgut towards

the distant haven of the promenade where the maid rubbed her hands on her smock with a distracted air and the doctor ran with

unseemly haste towards the house.

But then I stood there with the fish; I knew I should follow but couldn't. I turned and walked towards the sea away from the

house where what I didn't want to know was happening. They found me four hours later, by the rocky inlet round the Head. The

tide had come in and my feet were bleeding from the stones. The black car pulled up by the road on the headland and Maisie

walked from it. She clambered down the rocks towards me and said, you come home now. She's dead, isn't she, I said and Maisie

repeated, you come home now. So I went home.

So the light is up and the Moroccan is still banging his wooden support. It won't be long now till the priest walks out, stiff

as he was last Sunday, alb and cincture blowing in the same wind. Here it's easy to imagine that nothing changes. The pattern

of blood on what was once a monastery wall grows; each day another is shot and somehow nothing changes.

Death, I was to find, brought its privileges. As Maisie patched my knees and cleaned my feet she gave me goldgrain biscuits

to quieten me. I sat by the warmth of the range and heard my voice coming out, piping, almost cheerful. She's dead, isn't

she? Hush you, said Maisie, and gave me a biscuit. Tears came to my eyes and she gave me one more. And later, when I was brought

upstairs, the hush that fell on that sherry-filled room told me of a new dignity I had been blessed with. The priest and all

the uncles rose at once. I walked past the skirts of aunts with the gravitas of an actor who knew his hour was come. I wept

when the priest touched my hair, wept more when the priest stroked my cheek and the tears were real, even though they arrived

on cue. The arms of the grandfather clock held some strange fascination so I stared at them rather than at the faces around

me. They leapt forwards and the chimes sounded. Father entered and stood with his face by the window. I felt that we were

vying for this moment and that somehow I was winning hands down. Hand after hand touched my cheek, pennies were pressed into

my palm and all I had to do was stand and weep. And my father stood, stared out the window. His retiring soul kept the grief

intact and his reserve seemed shameful. He would suffer with it for years, both the shame and the grief, whereas I being young

had only the grief and an adequate stage upon which to display it.

Mouse came down later that evening. Mouse, who lived in the cottage up in Bloodybank, who was brought up by the aunt with

the dyed blonde hair and the bedroom slippers for shoes. He had been sent to get a bottle of milk by his brother and had taken

the longest of detours to get me to come out. I could see from his expectant face under the black hair that he hadn't heard

the news. Come on, he said, down the promenade to the amusements and to the corner shop and back. I can't, I said, my eyes

still wet. You leave him be now, Maisie said, coming from the dark of the kitchen with a tray of fruitcake.

Pourquoi,

said Mouse, who liked big words. Maisie pulled me back and slammed the door and I tried to imagine the sangfroid with which

he would accept the rebuff. Turning, shrugging, or walking backwards from the door, jingling the coins in his pocket. She

drew me upstairs, the tray in one hand, my collar in the other, and introduced me to a room full of a different set of mourners.

They drifted through for what seemed like days. The bell would ring and Maisie would run down and those I had known in other

guises would enter, their faces now set in masks of condolence. Maisie kept an endless supply of fruitcake sashaying up the

stairs, of cups of tea, glasses of sherry, goldgrain biscuits. After a while I must have fallen asleep for I remember being

carried upstairs, the wool of his suit brushing off my cheek, an intimacy to which I was quite unaccustomed. He laid me down

in the darkened room and said, don't you worry about anything. I could see him standing above me and his cheeks were wet now,

as if here he could allow himself tears. My voice came out calm and this surprised me, but now that we were alone, it was

as if my show of grief could be let vanish. I won't, I said. We'll make do, he said, won't we? And there was that hint of

uncertainty in his voice, as if maybe we wouldn't. We will, I said and felt resentful at being the one who must provide the

reassurance. What's my name? he asked me. It struck me as an odd question so I didn't answer for a bit and when he repeated

it I said, you're my father. No, he said, what's my real name? Sam, I said. Your name's Sam. That's right, he said, and he

wiped his cheek and left.