Suppressed Inventions and Other Discoveries (24 page)

Read Suppressed Inventions and Other Discoveries Online

Authors: Jonathan Eisen

These observations were repeated eight times, using in each instance growth of the filterable organisms in K Medium. The cultures examined were both twenty-four and forty-eight hours old. The qualitative results were always . . . the occurrence of small, oval, actively motile, turquoiseblue bodies in the cultures and the absence of these small, oval, actively motile, turquoise-blue bodies in the uninoculated control K Media.

From the two facts thus far arrived at, namely, that the small, oval, turquoise-blue bodies were actively motile and also that they were cultivable from K Medium to K Medium, it is surmised that these small, oval, motile, turquoise-blue bodies are indeed the filterable forms of the B. typhosus.

There is another even more direct procedure for establishing the identity of these small, oval, motile, turquoise blue bodies. It has been shown in previous communications

3

that agar cultures, or better, broth cultures of B. typhosus inoculated into K Medium, become filterable within eighteen hours' growth at 37°C. It should follow, inasmuch as not all of the bacilli appear to become filterable under these conditions, that at least some of the bacilli should have similar turquoise-blue granules within their substance if they are indeed passing to the filterable state. Also the free swimming filterable forms, the small, oval, motile, urquoise-blue bodies described above, should be simultaneously present.

Darkfield examination of such a culture eighteen hours old revealved unchanged, actively motile bacilli, bacilli with granules within their substance, and free swimming, actively motile granules. This culture examined in the Rife microscope with the quartz prism set at minus 4.8 degrees and with 5,000 diameters magnification, showed very clearly the three types of organisms just described, namely:

First, unchanged bacilli: These were relatively long, actively motile, and almost devoid of color.

Second, long, actively motile bacilli, each with a rather prominent granule at one end. The granule in such an organism was turquoise blue, reminiscent in size, shape, and color of the small, oval, actively motile, turquoiseblue granules found in the protein medium (K Medium) where, it will be recalled, no formed (rod shaped) bacteria could be demonstrated. These bacilli having the turquoise-blue granules were colored only at the granule end, the remainder of the rod being nearly colorless, in this respect corresponding to the unchanged (nonfilterable) bacilli just mentioned.

Third, free swimming, small, oval, actively motile, turquoise-blue granules, precisely similar, apparently, in size, shape, and color to those seen in the granulated bacilli just described.

From the fact that these small, oval, turquoise-blue bodies could be seen both in the parent rod and free swimming in the medium, it is assumed that these small, oval, actively motile, turquoise-blue bodies are indeed the filterable form of B. typhosus.

REFERENCES

1. James A. Patten Lecture, Northwestern University Bulletin, Vol. 32, No. 5 (September 28), 1931

2. Northwestern University Medical School Bulletin, Vol. 32, No. 8 (October 19), 1931, for full details.

3. Op. cit.

The Persecution

and Trial of

Gaston Naessens

The True Story of the Efforts to Suppress an Alternative Treatment for Cancer, AIDS, and Other Immunologically Based Diseases

Christopher Bird

Most secrets of knowledge have been

discovered by plain and neglected men

than by men of popular fame. And this is so

with good reason. For the men of

popular fame are busy on popular matters.

Roger Bacon (c. 1220-1292),

English philosopher and scientist

This is about a man who, in one lifetime, has been both to heaven and to hell. In paradise, he was bestowed a gift granted to few, one that has allowed him to see far beyond our times and thus to make discoveries that may not properly be recognized until well into the next century.

If the "seer's" ability is usually attributed to extrasensory perception, Gaston Naessens's "sixth" sense is a microscope made of hardware that he invented while still in his twenties. Able to manipulate light in a way still not wholly accountable to physics and optics, this microscope has allowed Naessens a unique view into a "microbeyond" inaccessible to those using state-of-the-art instruments.

This lone explorer has thus made an exciting foray into a microscopic world one might believe to be penetrable only by a clairvoyant. In that world, Naessens has "clear-seeingly" descried microscopic forms far more minuscule than any previously revealed. Christened somatids (tiny bodies), they circulate, by the millions upon millions, in the blood of you, me, and every other man, woman, and child, as well in that of all animals, and even in the sap of plants upon which those animals and human beings depend for their existence. These ultramicroscopic, subcellular, l i vi n g and reproducing forms seem to constitute the very basis for life itself, the ori

144

gin of which has for long been one of the most puzzling conundrums in the annals natural philosophy, today more sterilely called "science."

Gaston Naessens's trip to hell was a direct consequence of his having dared to wander into scientific terra incognita. For it is a sad fact that, these days, in the precincts ruled by the "arbiters of knowledge," disclosure of "unknown" things, instead of being welcomed with excitement, is often castigated as illusory, or tabooed as "fantasy." Nowhere are these taboos more stringent than in the field of the biomedical sciences and the multibillion dollar pharmaceutical industry with which it interacts.

In 1985, Gaston Naessens was indicted on several counts, the most serious of which carried a potential sentence of life imprisonment. His trial, which ran from 10 November to 1 December 1989, is reported here.

When I learned about Gaston Naessens's imprisonment, I left California, where I was living and working, to come to Quebec to see what was happening. I owed a debt to the man who stood accused not so much for the crimes for which he was to be legally prosecuted as for what he had so brilliantly discovered during a research life covering forty years. To partially pay that debt, I wrote an article entitled "In Defense of Gaston Naessens," which appeared in the September-October issue of the New Age Journal (Boston, Massachusetts). That article has elicited dozens of telephone calls both to the magazine's editors and to Naessens himself.

Because the trial was to take place in a small French-speaking enclave in the vastness of the North American continent, I felt it important, as an American who had had the opportunity to master the French language, to cover the day-to-day proceedings of an event of great historical importance, which, because it took place in a linguistic islet, unfortunately did not make headlines in Canadian urban centres such as Halifax, Toronto, Calgary, or Vancouver, not to speak of American cities.

When the trial was over, Gaston Naessens asked me, over lunch, whether, instead of writing the long book on his fascinating life and work that I was planning, I could quickly write a shorter one on the trial based on the copious notes I had taken. He felt it was of great importance that the public be informed of what had happened at the trial.

I agreed to take on the task because I knew that a great deal was at stake, not the least of which are the fates of patients suffering from the incurable degenerative diseases that Naessens's treatments, developed as a result of his microscopic observations, have been able to cure.

The tribulations and the multiple trials undergone by Naessens will come to an end only when an enlightened populace exerts the pressure needed to make the rulers of its health-care organizations see the light.

DISCOVERY OF THE WORLD'S SMALLEST LIVING ORGANISM

When the great innovation appears, it will

almost certainly be in a muddled, incomplete,

and confusing form . . . for any speculation

which does not at first glance look crazy, there is no hope.

Freeman Dyson, Disturbing the Universe

Early in the morning of 27 June 1989, a tall, bald French-born biologist of aristocratic mien walked into the Palais de Justice in Sherbrooke, Quebec, to attend a hearing that was to set a date for his trial. On the front steps of the building were massed over one hundred demonstrators, who gave him an ovation as he passed by.

The demonstrators were carrying a small forest of placards and banners. The most eye-catchingly prominent among these signs read: "Freedom of Speech, Freedom of Medical Choice, Freedom in Canada!"; "Long Live Real Medicine, Down With Medical Power!"; "Cancer and AIDS Research in Shackles While a True Discoverer is Jailed!"; "Thank you, Gaston, for having saved my life!"; and, simplest of all: "Justice for Naessens!"

Late one afternoon, almost a month earlier, as he arrived home at his house and basement laboratory just outside the tiny hamlet of Rock Forest, Quebec, Gaston Naessens had been disturbed to see a swarm of newsmen in his front yard. They had been alerted beforehand—possibly illegally—by officers of the Surete, Quebec's provincial police force, who promptly arrived to fulfill their mission.

As television cameras whirred and cameras flashed, Naessens was hustled into a police car and driven to a Sherbrooke jail where, pending a preliminary court hearing, he was held for twenty-four hours in a tiny cell under conditions he would later describe as the "filthiest imaginable." Provided only with a cot begrimed with human excrement, the always elegantly dressed scientist told how his clothes were so foul smelling after his release on ten thousand dollars bail that, when he returned home, his wife, Francoise, burned them to ashes.

It was to that same house that I had first come in 1978, on the recommendation of Eva Reich, M.D., daughter of the controversial psychiatristturned-biophysicist Wilhelm Reich, M.D. A couple of years prior to my visit with Eva, I had researched the amazing case of Royal Raymond Rife, an autodidact and genius living in San Diego, California, who had developed a "Universal Microscope" in the 1920s with which he was able to see, at magnifications surpassing 30,000 fold, never-before-seen microorganisms in living blood and tissue.*

Eva Reich, who had heard Naessens Toronto, told me I had another "Rife" through Vermont to a region just north of the Canadian-American border that is known, in French, as "L'Estrie," and, in English, "The Eastern Townships." And, there, in the unlikeliest of outbacks, Gaston Naessens and his Quebec-born wife, Francoise (a hospital laboratory technician and, for more than twenty-five years, her husband's only assistant), began opening my eyes to a world of research that bids fair to revolutionize the fields of microscopy, microbiology, immunology, clinical diagnosis, and medical treatment.

Let us have a brief look at Naessens's discoveries in these usually separated fields to see, step by step, the research trail over which, for the last forty years—half of them in France, the other half in Canada—he has travelled to interconnect them. In the 1950s, while still in the land of his birth, Naessens, who had never heard of Rife, invented a microscope, one of a kind, and the first one since the Californian's, capable of viewing living entities far smaller than can be seen in existing light microscopes.

In a letter of 6 September 1989, Rolf Wieland, senior microscopy expert for the world-known German optics firm Carl Zeiss, wrote from his company's Toronto office: "What I have seen is a remarkable advancement in light microscopy ... It seems to be an avenue that should be pursued for the betterment of October 1989, Dr. Thomas Applied Biology at the Georgia Institute of Technology (Georgia Tech), who made a special trip to Naessens's laboratory, where he inspected the microscope, wrote:

give a fascinating lecture in

to investigate. So I drove up

science." And in another letter, dated 12 G. Tornabene, director of the School for

Naessens's ability to directly view fresh biological samples was indeed impressive . . . Most exciting were the differences one could immediately observe between blood samples drawn from infected and noninfected patients, particularly AIDS patients. Naessens's microscope and expertise should be immensely valuable to many researchers.

It would seem that this feat alone should be worthy of an international prize in science to a man who can easily be called a twentieth-century "Galileo of the microscope."

With his exceptional instrument, Naessens next went on to discover in

*

"What Has Become of the Rife Microscope?," New Age Journal (Boston, Massachusetts), 1976. This article has, ever since, been one of the Journal's most requested reprints.

Developments in microscopic techniques have only recently begun to match those elaborated

by Naessens more than forty years ago.

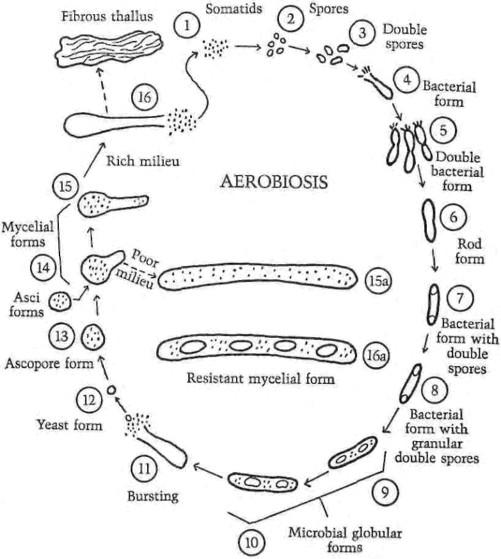

the blood of animals and humans—as well as in the saps of plants—a hitherto unknown, ultramicroscopic, subcellular, living and reproducing microscopic form, which he christened a somatid (tiny body). This new particle, he found, could be cultured, that is, grown, outside the bodies of its hosts (in vitro, "under glass," as the technical term has it). And, strangely enough, this particle was seen by Naessens to develop in a pleomorphic (form-changing) cycle, the first three stages of which—somatid, spore, and double spore—are perfectly normal in healthy organisms, in fact crucial to their existence. (See Figure 1.)

Even stranger, over the years the somatids were revealed to be virtually indestructible! They have resisted exposure to carbonization temperatures of 200°C and more. They have survived exposure to 50,000 rems of nuclear radiation, far more than enough to kill any living thing. They have been totally unaffected by any acid. Taken from centrifuge residues, they have been found impossible to cut with a diamond knife, so unbelievably impervious to any such attempts is their hardness.