Tailor of Inverness, The (12 page)

Read Tailor of Inverness, The Online

Authors: Matthew Zajac

As we left Hungary, on June 29

th

, we knew that people had begun to take advantage of the newly-relaxed

Hungarian-Austrian

border, but we were unaware that up to 150,000 East Germans were beginning to flood into Hungary in order to escape to the West. The Hungarian authorities made no effort to stop them and actually set up refugee camps for them. Eventually, on September 11

th

, the Hungarians simply opened the remaining barriers and they were free to leave.

Our journey to Prague, via Bratislava, was uneventful. The Czech border was more akin to the ones I remembered from the ’70s, threatening and unfriendly. I was struck by the thickness of the forest on either side of the motorway to Prague. Knowing about the grim oppressiveness of the Czech regime, I wondered if this was intended to hide the country from us. We stayed for only one night in Prague, camping at Branik by the River Vltava. The campsite staff were cold and brusque. It took a long time to check our passports, including a call to the local police to register our arrival. There were a lot of holidaying East Germans at the campsite. We pitched our tent next to a young East German family and got talking to them, sharing a beer.

News of the Hungarian relaxation had spread, but these people were sceptical about the idea of a better life in the West. They had jobs, a decent house, security. They were happy to stay at home and see how things developed. As it turned out, the Czech leaders couldn’t tolerate the stream of East Germans moving through their country to Hungary. They eventually sealed their border with the treacherous Hungarians and Czechoslovakia became the only country that East Germans could travel to without a visa. By early September, over 4,000 were camping in the gardens of the West German Embassy in Prague and more were arriving every day. On the evening of September 30

th

, the West German Foreign Minister, Hans Dietrich Genscher, himself an escapee from the DDR in

1952, arrived at the Embassy after negotiating with his East German and Soviet counterparts Oskar Fischer and Eduard Shevardnadze. He announced to the muddy campers that their wait had come to an end and that they would all be taken in special trains to West Germany. On the following day, train after train carried around 17,000 East Germans to the West. This event marked the beginning of the end for the DDR. A clear demonstration of the will of ordinary people, it led directly to the collapse of the Wall.

Despite the brevity of our stay in Prague, it was easy to appreciate the city’s beauty. It’s a popular tourist and party destination today, but its atmosphere was very different then. We would have liked to have stayed longer, to have visited all its beautiful buildings and to have soaked up its history and culture, but its sobriety then and our awareness of its hardline, suffocating government made us happy to leave it behind.

Besides, I was eager for my home from home, for Adam and Aniela and the bucolic charms of Lesna.

The journey from Prague was a distance of only 183

kilometres

, driving north-east to the border in the Karkonosze Mountains at Jakuszyca and on via Szklarska Poreba and Swieradow Zdroj to Lesna. Having travelled the route from Szklarska Poreba several times in my childhood its familiarity returned to me as we approached Lesna. I recognised the wooden houses of Swieradow and the stretch of open road through farmland where we had encountered Soviet military vehicles in 1967. We slowed down for a few kilometres, keeping our distance from a drunken moped rider, who swayed and wobbled from one side of the road to the other. It looked like he’d been to a market in Szklarska Poreba, his handlebars were weighed down with plastic bags full of vegetables and cooking oil, which made him even more unstable. Maybe the same thing happened every week.

Lesna hadn’t changed much. The little pink-painted pub was still there, next to the driveway. We turned into it and trundled up to the house. A little boy saw us and ran in to call his grandparents. This was Wojtek, Ula’s five-year-old son, who was spending his summer holidays in Lesna while Ula worked at her new home in Gdansk. Adam and Aniela were

older and greyer, not quite so sprightly but full of warmth and happiness at our arrival. They hugged and kissed us and exclaimed that Virginia was very beautiful.

‘Shall I say wife?’ asked Adam, with a twinkle in his eye, knowing that we weren’t married. Adam hadn’t lost his sense of humour, but he had developed gout. He still put thick slabs of butter on his bread when Aniela wasn’t looking and she’d banned him from smoking in the house, but he still puffed away in the garden. We sat out there and drank some of the whisky we’d brought. Mr. and Mrs. Wraga, the vet and his wife, came over to greet us, delighted to see that I had grown into ‘a fine young man’. A man turned up to deliver a couple of huge cabbages and a woman appeared through the trees at the end of the garden carrying a shopping bag full of meat. Adam no longer received his meat from the abbatoir. The drink had taken over Jan the Butcher’s life. It had killed him a few years earlier.

We stayed in Lesna for a week. I revelled in the nostalgia of recognising childhood haunts. Ula made the long journey from Gdansk to see us. We swam in Lake Czocha, picked cherries in the garden and I met friends who had now grown up. Ella Wraga was a teacher at what she sternly called ‘The House of Correction’ in Szklarska Poreba, a residential school for young offenders. Wladek Limont was visiting his parents, the Argentinian Communist and his wife. Wladek was an electrician in the tank factory in Gliwice. With the end of the Cold War imminent, and the prospect of free-market reforms, Wladek feared for his job. His factory was out of date and overmanned.

We spent most of our time sitting in the garden, eating tomatoes and drinking vodka, sometimes Adam’s

bimber

, his home-made hooch. As in the past, friends and neighbours would turn up for a chat and a drink. Aniela and Mrs. Wraga sang us songs and showed us photographs of their youth.

Adam recounted his education in speaking English through Radio Free Europe and how amused he was to learn about the royal ‘we’. ‘We want a wee wee (a piss)’ had become one of his English catchphrases. I quizzed him about his visits to Gnilowody but he wasn’t very forthcoming, describing it as a backward place. It wasn’t the same, there was no one there he knew. It wasn’t worth seeing. He was reluctant to say any more. It seemed to me that there was a lot more to say about it all. I had made the recordings which form part two of this book during the previous year and they had stimulated my curiosity about Gnilowody and Podhajce, but Adam was wary and reticent, albeit with a smile on his face. For him, it was best to leave all that in the past. I didn’t press him. I reasoned that he was only sixteen or seventeen when he was taken away by the Germans and his memories might have been too painful. I refrained from probing him about his experiences as a forced labourer. I could see that, like so many war survivors, Adam was happier to enjoy the moment without looking back.

Our visit to Lesna enabled me to reconnect with my Polish family, to introduce Virginia to them and to revisit an important part of my childhood. For reasons which still aren’t clear to me, – immaturity? – naivety? – respect for the words and opinions of my father and Adam? – the still-existing blanket of oppression in Eastern Europe? – I hadn’t felt a pressing need to investigate my family’s past more deeply. I was simply happy to have returned. What was clear was that

fundamentally

important reforms had been taking place in Eastern Europe, even during the 18 days of our trip. We had been lucky enough to have spent time with Misha, whose analysis of the political situations in the Eastern Bloc countries would prove to be so thorough and perceptive, articulated brilliantly in his 1990 book

The Rebirth of History

. His enthusiasm for, and anticipation of what was unfolding were infectious. However, enthusiasm and anticipation weren’t reflected in the

moods and attitudes of Adam and Aniela and the other older Poles, Hungarians and Czechs we encountered. The tragedy and upheaval of the war, followed by over 40 years of Communist rule, had engendered scepticism and caution. Sure, they were happy to see the beginnings of liberalisation and freedom of movement, but they weren’t sure yet that it would last. The Communists were still in power, and who was to say that new, non-Communist politicians would be any better?

Leaving Adam and Aniela and Lesna had always been an emotional experience in my childhood and it was no different this time. In fact, it was even more moving. We all found it difficult to speak as we made our farewells. We just hugged and wished each other well. I promised to return soon, and had to take deep breaths as we drove along the tree-lined road out of town, reliving all the farewells of my past: my father gripping the steering wheel, wiping away tears as he used the mechanical necessities of driving to control himself.

As I left Lesna on that day in 1989, I knew that I had reconnected, but I was also painfully conscious of the

inadequacy

of my reconnection. So much of my life had nothing to do with Poland and yet here I was, weeping for my distant family and a home I had never seen, Gnilowody, that place from another time which had taken on a kind of mythical status. I wept for our parting from Adam and Aniela, but I wept even more for selfish reasons, for my own sense of incompleteness. I don’t think I understood this fully at the time. I simply felt it: a hole in the pit of my stomach, a longing, an ungraspable desire.

We stopped for a night in Berlin on our trek west. It was a relief to be with Tom, free from the stresses of communicating in my limited Polish, able to recount our journey to a

sympathetic

ear. We drank in a Bohemian bar. The barman wore nothing but a diaphanous black shirt, a pair of tackety boots and a jockstrap. We walked to the Brandenburg Gate and

stood on an observation platform which gave us a view over the Wall. Virginia had never seen it before and it upset her. We speculated about the changes that were taking place and wondered how many more years it would remain. We didn’t imagine that it would come down in a matter of months. We set off early the following morning and chugged all the way to Ostend. One of the car’s engine cylinders had given out, reducing its power so that instead of sailing past the little Trabants on the East German autobahn, we kept them company. We made it to the ferry and kept going all the way to Dalston, arriving home at midnight, elated and exhausted. I had finally made my return.

During the previous year, my father had been admitted to hospital for tests due to low blood pressure. The doctors identified a thickening of his blood and high cholesterol levels and prescribed a regime of anti-coagulant drugs. Unfortunately, he left the hospital more ill than he was when he was admitted having contracted a streptococcal infection of his blood there, the result of inadequate hygiene, and it knocked him for six. He was in and out of hospital for the following year, receiving heavy intravenous doses of antibiotics to fight the infection. He was considerably weakened and lost a lot of weight. By the summer of 1990, he had made a reasonable recovery, though he was diminished. Always a big, hearty fellow he was thinner now, and weaker. He wanted to return to Poland, and Virginia and I were happy to drive him and my mother for our second visit in a year.

The Wall had collapsed in November ’89, the Velvet Revolution had taken place in Czechoslovakia, the Ceausescu regime had been violently overthrown in Romania and Bulgaria and East Germany had held their first free elections. Eastern Europe was seething with new energy which we wanted to witness for ourselves. I drove Mum and Dad to London from

Inverness and we set off for Poland the following day. We stopped for the night at Herleshausen.

Even though we knew what had happened in Germany, we could hardly believe the new reality of the border between East and West when we saw it the next morning. It was deserted. The gun turrets had been dismantled, the barriers removed. The buildings where we’d sweated and fretted with our forms and passports were empty and boarded up. We had to slow down, to see that this had really happened, to mark the occasion and savour the freedom of the border which had disappeared. For those euphoric, surreal moments, I felt as if we were floating in a happy dream, that a dead weight was being lifted from our shoulders. It all happened so quickly. All we did was drive past a few empty buildings, but it really felt like we were entering the Promised Land, a new world.

Money was already being pumped from West to East and we passed large-scale road works and drove on newly-surfaced stretches of the old autobahn, alternating with the

clunka-clunka

stretches of old concrete blocks which we were so familiar with. Without the strictures of the old transit visa, we took the wonderful liberty of turning off the autobahn and spending a few hours in the centre of Dresden. It was dominated by the ruins of its magnificent old Baroque cathedral, a monument to the city’s near-total destruction during the

firestorms

caused by Allied carpet-bombing in 1945. (It was restored to its former glory and reopened in 1995.) As we strolled around the ruins, I could never have imagined that 21 years later I’d be performing my play about my father in this city. We bought ice cream and set off for the final 100 kilometres of our journey and the open arms of Adam and Aniela.

That August, Western Poland seemed like one big car boot sale. Thousands of Poles were scurrying back and forth across the German border to buy goods, any goods: chocolate,

disinfectant, power tools, cuddly toys, Coca Cola. They would return to Poland with overloaded cars to their chosen town and set up shop. Sometimes, the Poles would trade in Germany, carrying honey and vodka for the Germans. Suddenly, the free market was everywhere. State-run industries were being dismantled and sold off. Factories were closing or being

streamlined

, shedding thousands of workers in the process. The car boot sale had become a vital necessity for many Poles.

We enjoyed another happy reunion with Adam and Aniela. Being there with my parents for the first time since 1974 gave the occasion an added poignancy, especially after my father’s illness. As in the past, friends and neighbours visited and the vodka glasses were filled round the garden table, but the celebrations of the ageing generation were more sedate and measured.

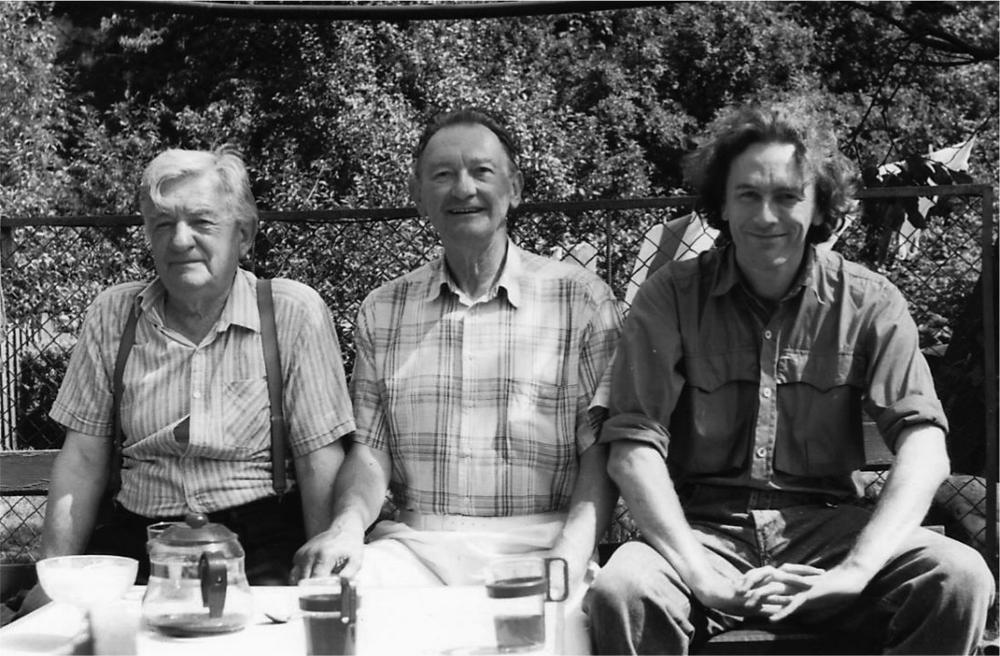

Adam, Mateusz and me, Lesna 1990

During our stay in Lesna, we were surprised to discover a street theatre performance in the town square by the

Krakow-based

Teatr KTO. It was part of a festival whose centre was the small city of Jelenia Gora, some 60 kilometres away. We

introduced ourselves to members of KTO, including its artistic director, Jerzy Zon. Jerzy invited us to visit them in Krakow. A couple of days later, we went to Jelenia Gora for more of the festival and watched a spectacular, sculptural street

performance

by a visiting French company. The performers were completely white, white clothes, white painted faces, legs and hands. They performed individually and in twos and threes like moving statues, operating a series of strange mechanical contraptions of wheels, cogs, poles and metal cages which moved slowly and gracefully, imprisoning them, liberating them and elevating them. This was accompanied by industrial rock music, played by the company’s musicians sitting on a black metal truck which had been fitted out with pipes, horns and drums.

We were in Poland for seventeen days. In the middle of our stay, Virginia and I left my parents for a few days and took the car to Krakow, stopping at Gliwice on the way to visit Wladek Limont and his young family. They were living in a flat in a standard post-war suburban housing scheme, an ordinary Polish working family. In true Polish style, they greeted us with generous hospitality and gifts of vodka and a crystal butter dish. The tank factory was still going, but the outlook for Wladek’s job remained uncertain. He wanted to come to England to work he told me. He hoped I could help him. I was pessimistic about this proposition, having no connections whatsoever with his trade back in Britain, and knowing that he would have to work illegally, but I said I’d see what I could do. As it turned out, I didn’t succeed in finding Wladek work and we eventually lost touch.

In Krakow we hooked up with our new friends at Teatr KTO, seeing a couple of performances and talking with them about possible co-productions. We pursued this idea for over a year and fixed on the suggestion of the company’s dramaturg and writer, Bogdan Pobiedzinski for an adaptation of William

Golding’s novel

The Spire

. This tells the story of an ambitious medieval bishop and his relationship with a group of

stonemasons

who have been commissioned by him to build the tallest spire in England. Bogdan proposed this story as a starting point for an allegorical play about the reconstruction of Poland and Eastern Europe and the fundamental influence western free-market capitalism would have on it. It was a good idea, which sadly never came to fruition. Our company at the time, Plain Clothes Productions, was new and though we had several notable successes during the ‘90s, we never gained sufficient stability or capital to exploit all our opportunities. Teatr KTO still exists, retaining several of its original members. The principle of ensemble theatre has been central to the

development

of Polish theatre, unlike the UK where theatre has depended far more on the initiative of individuals.

I was old enough to be admitted into Auschwitz this time. We spent most of a day there, walking through the exhibitions. Each country which had citizens who were victims had its own exhibition and I was struck by the contrast between the Dutch and Polish exhibitions. The Dutch explained the history of the Jewish community in Holland, describing its many impressive achievements and telling the story of the Nazi persecution of Dutch Jews. The Polish exhibition did not mention Jews. It referred to its victims only as Poles. Of course, there were many thousands of non-Jewish Polish victims, but the great majority was Jewish. The Polish authorities had chosen to ignore this fact. In one room of the Polish

exhibition

, there were lists of victims in alphabetical order. I found a group of Zajacs, about ten of them. Perhaps one or two were distant relatives.

The exhibitions were situated at Auschwitz I, the original concentration camp. They provided more detail to facts which I was familiar with: transports, routes, dates, camp conditions, methods of extermination, ‘medical experiments.’ There were

many photographs and the well-known heaps of personal possessions, spectacles, suitcases and shoes.

Most of Auschwitz I had been given the form of a

conventional

museum which mediated the experience, enabling the visitor to receive its horrific evidence with a degree of

objectivity

. This didn’t prevent the obvious distress of some young visitors on the day we were there and there were many visitors who ventured no further. But it was at Auschwitz II, Birkenau, where I found myself more deeply moved.

There are no exhibitions here, just the desolate wide expanse of the huge barracks with the stone chimneys of each barrack standing alone in rows like gravestones and the infamous archway with its railway line running the length of the camp to end close to the ruined gas chambers and crematoria. There’s a stone memorial here. The whole place was silent. The absence of birdsong at Birkenau has become something of a cliché, but we heard none, and saw only one bird, a hawk, drifting in the still air. In the woods behind the memorial, where improvised cremation pits had been used when the volume of corpses exceeded capacity, we tried to absorb the scale of this industrial factory of murder and wrestled with the reality of it, that human beings had planned and constructed it. We knew all this objectively, of course, but there was something visceral about standing in this place where it had actually happened. We felt compelled to see everything and by the end of the day, I was in a state of outrage.

Members of my own species had done this and because of this stark fact, I was tainted, responsible. Every living, mature human being is responsible. Perhaps this is the real meaning of what I have always considered to be the most evil,

objectionable

Christian concept, that of original sin. Maybe this really refers simply to the fact that we humans are capable of terrible acts and this has been distorted into the idea that we are guilty from birth.

We returned to Lesna and our anxious relatives, a few hours late. Ula had already arrived with Wojtek. She was in the process of building a large new house with her husband Janusz in Gdansk, not an easy task at the time as materials were often expensive and hard to come by. They needed to finish their roof. Adopting the new spirit of enterprise and freedom of movement, Ula reckoned she could buy what she needed more cheaply in Ukraine. She wasn’t allowed to exchange zloty or any other currency for Soviet roubles in Poland or Ukraine, so she purchased a sack of American chewing gum with the equivalent of two days wages. She then travelled the 900 kilometres to Netishyn in Western Ukraine, where her Polish mother-in-law was working as a cook with a group of Polish building workers who were assisting the Ukrainians in the construction of a new nuclear power plant. I guess chewing gum was a luxury item in the Ukrainian market at the time. She sold her sackful and purchased enough tinplate roofing for the entire house, including delivery. The tinplate arrived in Gdansk with the building workers. The workers travelled in a bus and they were followed by two trucks, full of the Ukrainian goods they had bought, including the tinplate.

The remainder of our holiday was spent quietly in Lesna, socialising in the garden, taking my parents to Czocha and Swieradow, walking in the forests and hills around Szklarska Poreba and visiting Ella Wraga at her apartment there. As always, our parting from Adam and Aniala was tearful. My Dad hugged his younger brother and kissed him on the cheek, telling him to take care of himself and to heed Aniela’s

exhortations

about his diet, his smoking, his heart. As we drove away from the house, we didn’t know that this was their final parting.

Dad died at around 7.15am on March 11

th

1992. He’d just cleared the car windows of snow, ready to take mum to the railway station. She was going to Leeds to see my sister Angela.

Just before they set off, Dad remembered a sample of material he wanted Angela to look at. He was planning to make her a coat from the material. He was often a man in a hurry and he rushed upstairs to fetch the sample. In his workroom, he suffered a massive heart attack. Mum heard the crash as he fell and found him lying there. She hurried to the phone and called the doctor. She received an answerphone message. In a panic, she fetched Flora, our next door neighbour and she called 999. The paramedics were quick to arrive. They tried to restart Dad’s heart for over an hour, but it was no use. Myocardial infarction. Rheumatic heart disease.

I got the call from my sister Casia. It felled me.

Casia and I took the plane from London that afternoon and arrived home in time to see Dad before the undertakers took him away. He looked at peace on his bed, the big man, pale and cold. Left alone with him for a few minutes, I stroked his face. I was full of grief and so proud to be his son. He was such a kind, generous man, unassuming and open. I told him he would always be with me. I told him I was sorry that he wouldn’t meet my children, but promised that they would know of him.