Tailor of Inverness, The (18 page)

Read Tailor of Inverness, The Online

Authors: Matthew Zajac

We walk on down the hill and come upon a huge ruin next to a dilapidated metal sign which rustily proclaims that a market had once been held here. The ruin was the town’s main synagogue, its sheer size, along with that of the cemetery, a

testament to the size of Pidhaitsi’s exterminated Jewish

population

and the significance of Jewish culture to this region. Two decaying, monumental memorials to the death of a people, in the heart of a living town. I wonder whether the quiet, subdued atmosphere of the place is influenced by their presence, if the overwhelming brutality of the war years, coupled with decades of Soviet repression and the subsequent post-

communist

capitalist economic shock treatment, have left Pidhaitsi in a state of collective concussion.

Jewish Cemetery, Pidhaitsi 2003

Further down the hill, Bogdan leads me to a third such memorial, another mighty ruin, the former Polish Catholic church. I had seen it as the bus entered the town, a ghostly sentinel from the past greeting Pidhaitsi’s visitors from Ternopil. Like the synagogue, this is a crumbling shell, left alone to preach its silent commentary on the history of this place, testifying that once, Poles lived here.

Our walk is a sobering introduction to Pidhaitsi, something which Bogdan clearly felt compelled to give me. It firmly places my visit in its context: the war and its consequences, the effect

of the past upon the present. Without a common language, Bogdan has eloquently explained through this walk exactly where I am and the burden of history which the town’s

inhabitants

live with every day.

Polish Catholic Church, Pidhaitsi 2003

The old Polish woman Wlodzimierza is sitting on her porch when we return. I sit with her for a while. She is one of only five Poles who stayed in Pidhaitsi after the Polish population was deported west by the Soviets early in 1945, to Silesia and Pomerania, from the land the Poles forfeited to the Soviets to the land forfeited by the Germans to the Poles. Wlodzimierza and her mother couldn’t bear the prospect of leaving their home. They had always had good neighbours, and despite some intimidation during the immediate post-war years, her life in the town has been tolerable. She shows me an old book about the region and turns to pages about Pidhaitsi. It displays a statistical table from 1900: 600 houses, population 5,646 comprising 760 Poles, 1,007 Ukrainians and 3,879 Jews.

Wlodzimierza had a brother, now dead, who settled in South

Wales after the war, working in the pits. He had been in the Polish army. Like my uncle Kazik, he had escaped the German and Soviet armies in 1939 to make his way to Britain. She had visited him once, in the late ‘80s during the Gorbachev thaw, and shows me photographs of their happy reunion. I think he suggested that she stay with him in Wales, but she preferred to return home, where she endured.

Filled with anticipation at the prospect of tomorrow’s visit to Gnilowody, I can’t sleep as I lie in my bed at Bogdan and Hala’s. Dogs howl to each other across the village. They seem to give ghostly voice to the town’s pain, to the dead of Pidhaitsi, a chorus of wild heralds calling from the darkness.

Next morning, at around 11.00am, Tania's husband Taras turns up in his slightly battered Lada Niva. A slim, swarthy, handsome man, he is to be our driver for the day, which is overcast, but dry. We are going to Gnilowody, my father's birthplace. After all the years of thinking about this place, of creating pictures of it in my mind, of hesitation and

procrastination

over this visit and that great majority of my life when I hadn't thought about it at all, the hour has finally arrived. Will it be an anti-climax? Will we find anyone there who knew my father and his family, or will I simply meet a succession of blank, disinterested, or even resentful faces? Lesia assured me that I would be âsatisfied' by my visit, but neither she nor Bogdan had made any indication as to how.

By the time we drink coffee, smoke cigarettes and fetch Lesia from her house, its noon. Bogdan and Hala come too. It's a tight squeeze in the Niva. Throughout this day, I juggle with a stills camera, a video camera, a tape recorder and a microphone. We drive past the Polish church and turn right up a hill out of town, heading south east. Lesia prepares me.

âOnce it was a very big village, a very progressive village. But now there are only old people and drunkards. All the rest

went to cities.' After a few kilometres, we turn left on to a dirt track. The going is slow and bumpy, through the fields, but we don't have far to go, just three kilometres. We lurch down a little valley between sloping fields and round a bend. The trees and houses of Gnilowody appear, spread out on either side of a stream and the stagnant ponds which give the village its name, Rotten Water. Geese and ducks hurry away as we approach. Cows and a few horses graze among the little haystacks. Some of the inhabitants watch as we pass, mainly scarved

babchas

and their husbands, lifting themselves from their tasks.

We stop outside a neat, whitewashed house. A dark-eyed old woman in a white scarf, thick skirt, cardigan and Wellington boots comes out to greet us, accompanied by a rosy-cheeked younger woman with short hair who wears black jeans and a sweater. Bogdan takes charge, having clearly arranged this meeting. The old woman is named Tekla. A few years after my aunt Emilia (Milanja) died, at the age of 55 in 1961, her husband Pavlo took Tekla as his second wife. The younger woman is their daughter Milanja, named after my aunt. She explains that she was given my aunt's name to honour her memory. She has travelled from Ternopil for the day and is to be our guide.

Tekla chats away, adding her own warm comments about Aunt Emilia as she and Milanja lead us into the house. They have prepared for our visit and get busy with carrying plates of delicious food into the living room where I'm urged to sit. I can't, the room is far too interesting. It's decorated in the classic Ukrainian rural style, whitewashed, with religious and family pictures adorned with patterned cloths. There is my aunt and her husband in a treated, black and white

photographic

portrait from around 1930, a strikingly handsome couple looking at the camera. My aunt's face and expression are particularly arresting. She is very serious, almost grim-faced,

with strong features: dark hair and eyes; dark, arched eyebrows; a square wide jawline and full Cupid's-bow lips. Pavlo is also serious, but more boyish, with a look in his eyes which doesn't seem to be quite so sure or steadfast.

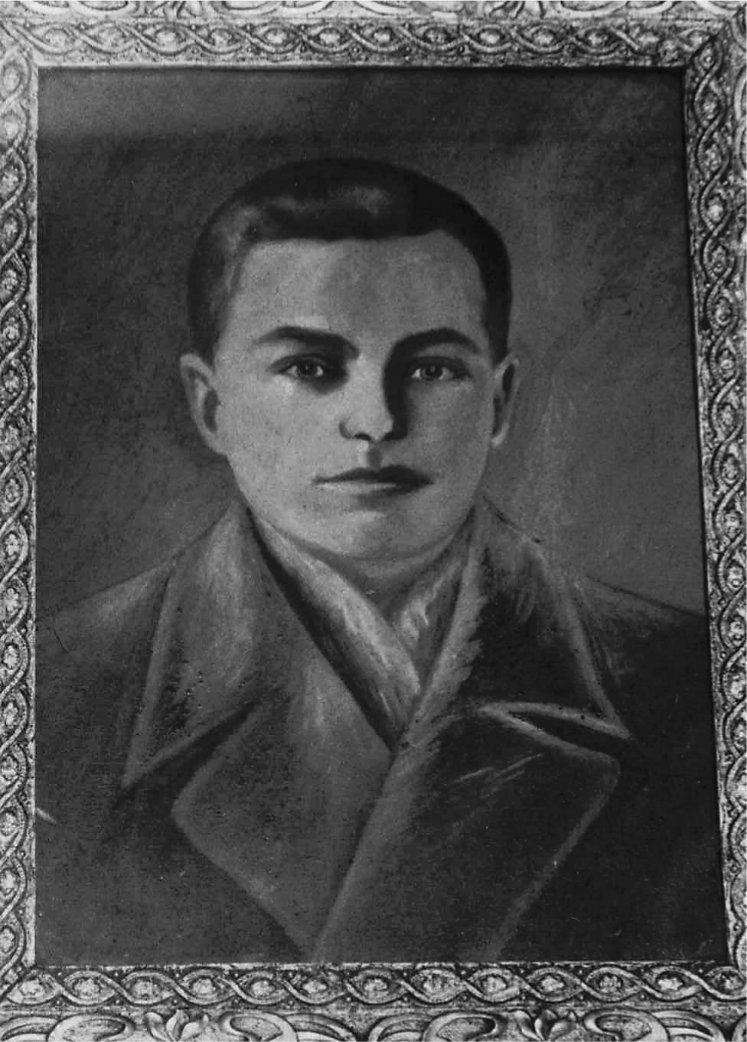

There is also a large portrait of my cousin, Teodosiy, which must have been made not long before his death in 1944. This one is in colour. His eyes and mouth are similar to Milanja's, though his face is rounder like his father's. He wears a dark blue coat and a green scarf. Tekla explains that when the Russians re-occupied the village in 1944, Teodosiy had been accused of helping the UPA and betraying Poles. She said that he had run away and hid in a bunker. A Russian soldier threw a grenade in after him.

Aunt Emilia and Uncle Pavlo c. 1930

Betraying Poles. As we eat and drink Tekla's vodka, and having listened to Mykola in Ternopil, I'm beginning to

understand

that there had been a war within a war in this region, between Poles and Ukrainians. You had to take sides, to declare yourself, or keep as quiet as you could to avoid the terror.

You needed the help of your friends and your community. Many communities were mixed, with villages of Ukrainians and Poles or Jews, while others were dominated by one ethnic group or sometimes exclusively Jewish, Ukrainian or Polish. It was similar to the situation in former Yugoslavia. Ukrainians, Poles and Jews had lived side by side in this region for centuries, while the inter-war Polish government, intent on asserting its rule here, had created new Polish settlements.

Teodosiy c. 1941

Gnilowody's Poles were in the former category. It had been a village of Poles and Ukrainians and according to my father there had been only one Jewish family. Mozolivka, my grandmother's birthplace was predominantly Ukrainian. Even though I had understood for some time now that Bogdan and Mykola

were Ukrainians, that all of their family was Ukrainian, I was only beginning to come to terms with the fact that (of course, you fool) my grandmother was Ukrainian. My father had never mentioned it. He did tell me that she followed the Orthodox church, so really I should have put two and two together, but he was so firmly Polish. I had lived all my life with my Polishness. He had barely mentioned Ukrainians. On the few occasions when Ukrainians were discussed in our house, it was usually to associate them with the role of some Ukrainians as brutal guards at Auschwitz, as Nazi collaborators. I was now only beginning to understand that my father's denial of his mother's nationality went deeper, that it must have been related to what had happened here in Galicia during the war, to the conflict between the Ukrainians and the Poles.

My grandfather was a Pole married to a Ukrainian. Galicia, and Volhynia to the north, were full of such mixed marriages. Lesia explained that then, in a mixed Polish-Ukrainian family like mine, the sons were registered as Poles, the daughters as Ukrainian. So Aunt Emilia was a Ukrainian.

Through Lesia, I relate Mykola's testimony to Tekla and Emilia. Can Tekla shed any light on it? She explains that she had never met my father and his brothers, though of course she had known my grandmother, Zofia, and Emilia. Yes, she knew about Mateusz being in the Soviet Army.

We finish our lunch and Milanja ushers us out. A few of the neighbours appear and explanations are made about who I am. This generates a degree of excitement and animated conversations ensue all around me as two of the old ladies recall the Zajac family and the first of many fond and respectful memories of my grandmother are described to me.

âAfter the war, she lived with Milanja and Pavlo. She was very sad because her husband had died and her sons were away to the west. But she was a very kind woman. She was very religious, she always carried her rosary. After her daughter

died, she lived alone and then she took in the local priest as a lodger. Everyone in the village respected her a great deal.'

Tekla and the other

babchas

study my features. One of them, rotund and laughing, puts her hand to my cheek and holds my shoulder, exclaiming her recognition, that she could see that I was a Zajac. âThey were all good-looking boys like you!'

I smile, gulp and catch my breath. She has a tear in her eye and seems delighted at the same time. So many years ago. That family. I hear mention of Kazik and Adam and

explanations

of where they had migrated to. They ask me if any of the brothers are still alive. Tekla and another old lady discuss Adam's visits to Gnilowody over 30 years previously as if they had been last week. A horse and cart trundle past. I understand that I am standing in a rare place in Europe, a place where peasants still exist, where many basic aspects of life on the land have remained unchanged for centuries and where the concept of time and place is quite different. And I am being welcomed as one of theirs. It doesn't matter that I have never set foot in the place, that I have only set foot in Ukraine a week earlier, I am one of theirs. My Polishness seems to be an irrelevance, or perhaps that is ameliorated by my Ukrainianness, my Ukrainian grandmother. As these thoughts are racing through my mind, I let them go. It doesn't matter. What matters is what is happening here and now, in front of me. I can reflect on it later.

Milanja leads us away from this little crowd. One or two of the neighbours decide to accompany us. Our visit is clearly something of an event. Lesia sticks by my side, assiduously translating as we walk through the village. Taras remains a little apart from us, watching and listening. I'm eagerly trying to absorb every moment: the images and sounds of the village, the new people, the words which are pouring from them. I am also trying to exploit my technical aids, switching from

the video camera to the tape recorder to the stills camera as I converse in my rudimentary Ukrainian/Polish and in English. My head is spinning.

We turn up a sloping track which leads to an avenue of silver birch trees at the back of the village. The cemetery lies at the end of the avenue and we follow Milanja through the gate. Most of the graves are lying to the right. Other, older ones are scattered haphazardly to the left. We arrive at a grave with a rectangular stone border. At its head lies a rough stone plinth topped with a cross. It is about 2 metres in height and has been freshly painted silver by Milanja, before Easter. Sprucing up graves at Easter is a tradition here. There is no inscription. âThis is your grandmother's grave.'

I stand for a few quiet moments, thinking of Zofia, alone in her final years. The absence of an inscription seems to emphasise this for me, though it puzzles me. A wave of sadness heaves through me. My visit suddenly feels futile, 40 years too late. I should have known her when I was a child. And I feel anger, anger at being denied that knowledge by a cold ideology, by the triumph of fear. I don't cry, though I come close. This anonymous grave is all that's left of her here. Zofia Zajac, my fairytale granny, who once really did exist.

I photograph Zofia's grave and resolve to pay for an

inscription

on the stone. Milanja leads us to Emilia's grave. This one has an inscription carved into an inlaid blue heart, in Ukrainian, with a blue painted angel at its head. Emilia had died of heart disease. I recalled my parents had told me of a letter they had received from Emilia, around the time of my birth, 1959. In it, she explained her illness and requested that they send drugs for her which they couldn't get in the Soviet Union. Of course, they sent them. About three months later, they were returned by the Soviet authorities with the explanation that the Soviet medical services had no need of drugs from the west, that theirs were more than a match for anything to be found in Britain.

âWhere's Andrzej's grave, my grandfather's grave?

Gdzie jest dzadzki grob?

'

Lesia repeats the question in Ukrainian. Milanja looks at Bogdan. She doesn't know. Neither does anyone else. They discuss the issue.

âIsn't it here?' Lesia points vaguely towards the area at the other end of the cemetery where there are only a few graves and patches of clear grass. âNo one is sure, but they say it might be over there. Your grandfather died just after the war when people had very little, so maybe his grave is not marked. It could be somewhere else.' âWhere?' âThey don't know.' I frown. This doesn't seem to make sense.

I was told by my father that my grandfather had died in 1947 or 1948, though I didn't know the cause. There certainly would have been a great deal of hardship at that time. Collectivisation had been imposed on the community. The farmers had been dispossessed of their land. Our farm had been the largest in Gnilowody. Andrzej had been an influential man in the village. I couldn't understand why no one knew where he was buried, or why some kind of headstone or cross hadn't been erected after his death when times were better. By the end of the day, I began to understand a little more. I take a photograph of the vacant patch of the cemetery where Andrzej's remains possibly lie and we walk on.