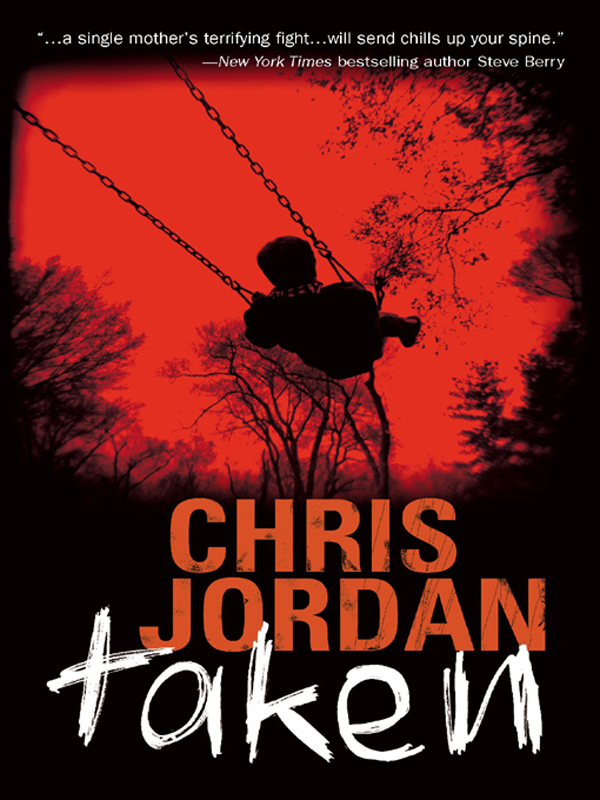

Taken

Authors: Chris Jordan

CHRIS JORDAN

For Lynn Harnett, forever and always.

The author wishes to thank Diane Shaw and all the good folks at Piscataqua Savings Bank for sharing details of financial intrigue.

FIELD OF GREEN

Fairfax, Connecticut

O

n a perfect day in the month of June, in a lovely field of green, my life starts falling apart. At five minutes after four in the afternoon, to be exact.

At ten of four things are still fine and dandy. I’m watching eagerly as the handsome boy with the aluminum bat steps out of the batter’s box and readjusts his gloves, just like A-Rod, his big-league hero. I lean forward in the dugout, but resist the impulse to shout encouragement. My son, tall and lanky for his eleven years, doesn’t mind the fact that his mom is an assistant Little League manager, but he has asked me not to shout from the sidelines like so many of the other parents. Parents who are, like, hideously uncool. His phrase. Tomas “Tommy” Bickford. My perfect, precious, truly gifted son. My amazing, maddening child. Amazing because he seems to be changing every day, sometimes from minute to minute. Maddening for the same reason, because I never know if he’s going to be my sweet little boy, goofy and affectionate, or if he’ll dis me with his soon-to-be-teen-stud coolness. Tommy can toggle between the two identities in the space of a heartbeat, and every time it happens it hits me like a soft blow to the belly.

At eleven he’s such a guy. And somehow I never imagined my son would be, well, a

guy

guy. What did I expect him to be? Did I think he’d stay my baby boy forever? Clinging to my apron strings? And I do wear aprons. Aprons inscribed with the logo for my catering company. I also make cookies. A thousand or so a day, for the upscale delis and restaurants in my neck of the Connecticut woods.

I like to think of myself as a warmer version of Martha Stewart. Warmer and a lot less wealthy. But doing okay in my own small way. Katherine Bickford Catering books over two hundred events a year. Peanuts compared to the really huge commercial catering firms, but more than enough to keep my twelve employees very busy indeed. Average event, eighty-five plates. Average charge per plate, sixty-two dollars. Do the math and you’ll discover that adds up to more than a million dollars gross. A million bucks! Of course, we showed a whole lot less than a million in profit, but still. And I really did start the business in my own kitchen. With a small, frightened four-year-old boy “helping” me sift the flour.

We’ve both come so far in the last seven years that it sometimes takes my breath away. Especially when I admit to myself that when we started out I was even more terrified than the four-year-old. Terrified of suddenly having to raise a child on my own. Terrified I would never get over the grief of losing Ted, the love of my life, my sweet husband. Terrified that I would simply vanish into the black hole of despair if I stopped moving or stopped mothering for even a minute.

Even now, seven years later, just thinking his name gives me a Ted-size pang of melancholy. Like a low, mournful note on a cello, quietly sounding in the deepest part of me. But the anxious fear is gone. Over time the grief has become regret, for all the things poor Ted has missed. Tommy on his first bicycle—

Don’t touch me, Mom, I can do it all by myself!

Tommy on his way to first grade, fiercely insisting that he not be accompanied into the school—the bravest kid in all the world that day.

Amazing boy. For the first month or so after Ted died, he came to our bed—my suddenly lonesome bed—and slept at my side in a fetal position, reaching out in his sleep as if he thought I, too, might vanish from his life. And then one day at breakfast he quietly announced that he was “too big” to sleep in his mommy’s bed. Hit me two ways, that one. Fierce pride that at four he had such a strong sense of self. And regret that he didn’t seem to need me quite as much as I needed him. At least while he slept.

How many hours did I stand in Tommy’s bedroom door that first year after Ted passed, watching him sleep? More than I care to admit. And yet just watching him helped me. As watching him now helps remind me of who I am. My first and most important identity: Tommy Bickford’s mom. Proud to be, even if he doesn’t want me shouting his name from the dugout.

What the hell, let him deal with it.

“Come on, Tommy! Clean stroke! Good at bat!”

Stepping back into the batter’s box, he shoots me a glare. Also a grin, like he knows Mom can’t help herself.

The pitcher, a husky kid who looks as if he’s been taking steroids—hasn’t, I’m sure, but he has that beefy look—peers in for the sign, flings back his arm and delivers the ball. Not exactly a fastball—I’m guessing 70 mph or so on his dad’s radar gun—but straight and true and heading right for the catcher’s mitt.

Tommy steps into the pitch with his bat level, swinging slightly up, and

bonk!

He’s made contact. The ball carries over the short-stop’s outstretched glove and rolls all the way out to where the left fielder waits, then scoops it up. Drops the ball, gets it again, makes a wobbly throw to the cutoff. Cutoff drops the ball but keeps it in front of him, very good. By which time Tommy is sliding into second—an unnecessary act of daring, but the boy loves to get his uniform dirty—and the winning run has crossed the plate.

Pandemonium. Our players throw their gloves in the air, letting out war whoops and girlish cheers, and Fred Corso, our bullnecked manager—he’s also the Fairfax County sheriff—punches his fist in the air and then strides out of our cinderblock dugout.

“Yes! Way to go, Tomas! Good hit, son!”

I keep forgetting, Tommy wants to be called Tomas now. Probably hasn’t reminded me more than a million times in the last two weeks, but good old Fred has remembered. Feeling a little chastened, and resisting the impulse to run out on the field and give my boy a hug, I remind his excited teammates that it’s time to line up and shake hands. Congratulate the opposing team, the Fairfax Red Sox, on a game well played.

We’re trying to instill sportsmanship and doing a pretty fair job of it, if I do say so myself. The losers look sheepish, slapping five without much enthusiasm, but everyone is polite and they get the job done.

I catch Tommy from behind and lift the hat off his head. Give his raven-black hair a scoodge—his word—and face him, grinning. “Nice going, Tommy! You really smacked it!”

“Thanks, Mom.” But he’s already backing away, afraid I’ll spoil his moment of manly triumph with a kiss. Then he stops, sidles up next to me, looking deeply serious. “You know what, Mom?”

“What?”

“I think I deserve an ice-cream sundae.”

I fork out the necessary money and he runs off to the snack trailer, which is parked next to the field for the games. Runs by Karen Gavner and her husband, Jake, who have twin girls on the team. Not especially gifted athletes, but good kids. Connecticut blondes, both of ’em, and studying to be heartbreakers. I’ve seen the way they look at Tommy, but if he’s discovered girls he hasn’t let me know about it. Which he might not, come to think of it.

“Meet me at the van!” I shout at his back.

He acknowledges with a bob of his head and then vanishes into the milling crowd of parents and players, high-fiving as he goes.

And that’s the last I see of him.

in my chair

T

he hated minivan. My poor Dodge Caravan has recently become the object of Tommy’s scorn. Am I not ashamed to be seen in the pathetic “Mini-Vee,” as Tommy calls it? What does it tell the world about me, to drive such a totally boring car? Actually, his phrase is “hideously boring,” not totally boring.

Totally

was last year’s favorite modifier. Everything is hideous now. Just the other day he ticked off all the reasons I should trade in the hideous Mini-Vee for a really cool Mini-Cee. Of course I bite. “Mini-Cee,” it turns out, is Tommy-talk for Mini Cooper.

“You mean that funny little car?” I asked him. “The one at the circus where all the clowns get out?”

“It’s made by BMW, Mom,” he informed me. “It’s not funny looking. It’s way cool. It would look good on us, trust me.”

It would look good on us.

Where did that come from, the idea of a car as a fashion accessory? Of course I know exactly where it comes from. TV, Internet, magazines, the neighborhood, in roughly that order. Beemers and Audis and Mercs are the vehicles of choice in our part of the world, but I’m aware of the Mini Coopers that Tommy so admires, because there are two of them just down the street, prominently displayed in the Parker-Foyles’ driveway. His and hers, color coordinated.

“No chance,” I told him. “Put it out of your mind. I’m a Caravan kind of girl.”

At which point his eyes rolled so high I thought they might get stuck in the back of his head. And that makes me laugh in recollection. Hey, I remember being embarrassed about the car my mother drove, too. My mother’s stodgy old Ford Fairlane station wagon, how embarrassing. And shame on me for thinking so at the time.

So I lean against the van on a perfect summer evening, waiting for my son. Scanning the field and parking lot for Tommy. Not seeing him.

Waiting.

For the first few minutes I’m not terribly concerned. There’ll be a line at the snack trailer. Friends to talk to. More hands to slap, kudos to receive. But then traffic clears enough for me to see the snack trailer, and there’s Jake Gavner closing the window, shutting down—sold out, no doubt—and my mom radar is drawing an empty screen. Can’t seem to pick up Tommy. Did he run back into the school to use the boys’ room? Unlikely. We’re ten minutes or so from home and I happen to know Tommy prefers to use his own bathroom whenever possible.

So I’m trying not to act overly concerned as I walk over to the closed-up snack trailer and rap my fist on the back door.

“Yo!” from inside.

“Jake! It’s Kate Bickford.”

The door swings open and Jake is there, flashing a quizzical smile. Nice-looking man with slight rosacea on his cheeks and a comfortable paunch he never tries to hide. Great with kids—somehow he remembers all the names, and who belongs to who.

“Hey, Kate! Dogs are gone.”

“Excuse me?”

“Hot dogs. We’re out. No slumming for you today.”

He winks. For the life of me I can’t think why Jake Gavner would be winking at me, and then I get it. The hot-dog conversation. Couple of weeks ago I was starving and ordered a dog with extra kraut. As I chowed down, we chatted about comfort food. Joking around that if any of my customers saw me eating hot dogs I’d lose business. Either that or they’d be expecting cheap tinned sausages as appetizers at the gala banquets. Wasn’t exactly a scintillating conversation, come to think, but apparently something about it stuck with Jake.

“No, no, I’m fine,” I tell him. “By any chance, did you notice where Tommy went?”

“Tommy? Nope. You lose him?” He looks around sharply, eyeing the empty field, the near-empty parking lot.

“He came over to get an ice cream,” I tell him. “Chocolate with chocolate sauce, hold the nuts. Thought you might have noticed if he wandered off with some other kids.”

“Tommy, huh? Nope. No ice cream for Tommy, that I recall.”

“He never showed?”

“I’d remember, Kate. The kid won the game. I’d have comped him a sundae. Always do that for game winners, if they try to pay.”

“Really? That’s nice of you. Um, maybe Karen served him?”

He shakes his head. “I had the counter and the coolers. Karen was on the grill.”

“Is she around?”

“She took the extra coolers home. Got to get the stuff back in the freezer, you know?” Jake studies me, senses my anxiety. “Call her. Maybe she saw him. But he probably went home with somebody else, is my guess.”

“Yeah,” I say. “Thanks.”

And turn away thinking, he wouldn’t dare. Not my son. Take off without telling me? Not Tommy. At the same time, the comment about game winners getting free ice cream bothers me. Did Tommy know? And if so, why hit me up for three bucks? Did he have other plans? Plans that included a little pocket change?

Now I’m more than uneasy. Call it anxious. Anxious but not quite ready to call 911. Or more directly, Sheriff Corso, our team coach. Because I can already hear Fred telling me not to worry. The boy was excited, okay? Getting that big hit went to his head. Enough so he forgot to tell Mom he was getting a ride home with somebody else. Some group of rambunctious teammates who wanted to praise him.

I hit Home on my cell and hear it chirping. My own voice comes on the line, suggesting I leave a message. “Tommy, are you there, honey? Pick up, please.”

But I’m keenly aware that Tommy hates letting the answering machine cut in. He’ll kill himself racing for the phone, even if there’s no prospect that the call is for him. Bruises on his shins to prove it.

Where’s my boy? And what is he thinking, scaring me like this?

I march to the gymnasium entrance, convinced he’s inside using the boys’ room, or more probably raising some kind of hell with his buddies. The entrance is locked, but I can see into the gymnasium. It’s dim and empty. And silent. No laughing boys. No lockers slamming. Nobody home. Just silence.

I hurry to the Caravan. I’ll just quick check at our house before calling Fred Corso.

I have to force myself not to stomp on the accelerator leaving the empty parking lot. Thinking, Tommy, how could you do this to me? Make me worry like this? Is this the way it’s going to be for the next five years? Scamming Mom for money, not coming home until the crack of dawn?

Get a grip,

I urge myself. One of the other mothers offered him a ride. He felt it would be impolite to say no, and they took off before he could tell me. Some variation on that. But still, no excuse. He knows I worry.

Already I’ve covered six blocks. Must have passed through two lights but have no recollection of it. Driving on autopilot while my frazzled mind cranks out scenarios. All of which conclude with me giving Tommy a big hug and telling him never do that again. Never make your mother think the worst might happen.

I’m held up on the last light on Porter Road. Elderly couple can’t get it together to actually go when the light turns green. “Q-tips,” Tommy calls them. Meaning elderly drivers with that soft white, cotton-ball hair peeking up over the seat backs. Can’t recall the last time I really blasted the horn, but this time I punch it hard and the driver jerks in his seat like he’s been shot and then lurches his Lincoln Town Car through the intersection. More horns, some of them directed at me.

Weaving through the confusion I’ve created, I cut into the intersection, get my lane and remember to use the turn signal for our street, good old Linden Terrace, coming up quickly on the left. Actually a cul-de-sac with a turnaround at the end, which cuts down on the through traffic and probably adds ten grand to the evaluation of all the homes there. Well worth it, we all agree. Not that I care about property taxes right now. Not with Tommy filling my head.

Almost there. Almost home. Third from the end. The big, cedar-shingled Cape-style beauty behind the two massive maples that have taken over the front lawn. One full acre, with commonly held woodlands behind. There’s a separate three-car garage, also shingled, which came in handy when I was starting up the catering business. It was the big garage that first sold Ted on the place.

You never know when it might come in handy,

he’d said. He was thinking “boat,” but for a while it held stacks of folding tables and chairs, crates of crockery. Totally against the local zoning laws, of course—no business activity allowed, not even storage—but my neighbors took pity on the young widow and looked the other way until I could afford to rent a proper warehouse. Much appreciated, that quiet act of kindness. Sometimes looking the other way is just what the doctor ordered. Better than casseroles left on the step or offers to babysit.

Give her time,

they must have urged each other, and now the garage was just a garage again and Tommy is eleven years old and giving his mother fits.

Leaving the van in the driveway, I bound up the breezeway steps, kick the screen door open and approach the inner door with key in hand. Because we always lock up and activate the alarm. Nice neighborhood, but still. Bridgeport is a mere three miles down the road, and in Bridgeport they have gangs and drugs and crime that sometimes manages to seep into suburban Fairfax. So we lock.

But the door is unlocked and the alarm isn’t sounding. And that can mean only one thing. I’m already heaving a sigh of relief as I enter the kitchen area.

“Tommy?” I call out. “Tommy! I was worried sick! What were you thinking?”

No response. Pretending he can’t hear me. Pretending he didn’t do anything wrong. Ready with a facile fib about how he did so tell me he was getting a ride home and it must have slipped my mind. Early-’zeimers, Mom. You’re losing it.

“Tommy?”

The TV is on in the family room. Low but audible. A Sony PlayStation game. It will be

Tenchu: Wrath of Heaven,

his current favorite, or maybe the new

Tomb Raider

. But game or not, the little scamp can hear me fine. And now he’s starting to piss me off. He should be here in the kitchen, ready with an apology, however lame.

“Tommy! Turn off the TV!”

I march into the family room, expecting to see my son perched in front of the big-screen TV, manipulating the controls of his precious PlayStation.

But Tommy isn’t there.

“Hello, Mrs. Bickford. Take a seat, would you, please?”

There’s a man in my brown leather chair. He has Tommy’s video-game control box on his knee, working the joystick with his left hand. His face is obscured by a black ski mask.

In his right hand is a pistol, and he’s aiming it at me.