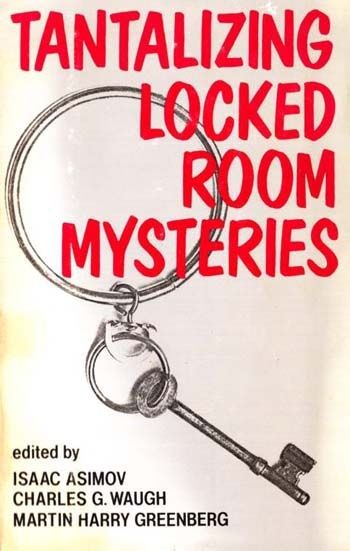

tantaliz

Table of Contents

THE ADVENTURE OF THE SPECKLED BAND

THE 51st SEALED ROOM; OR, THE MWA MURDER

Copyright © 1982 by Isaac Asimov, Charles G. Waugh, and Martin Harry Greenberg

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electric or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Publisher.

All the characters and events portrayed in these stories are fictitious.

First published in the United States of America by the Walker Publishing Company, Inc.

Published simultaneously in Canada by John Wiley & Sons Canada, Limited, Rexdale, Ontario.

Printed in the United States of America

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Kantor, MacKinlay. Copyright © 1930 by MacKinlay Kantor. Copyright renewed. Reprinted by permission of Paul R. Reynolds, Inc. Woolrich, Cornell. Copyright © 1937 by Cornell Woolrich. Copyright renewed 1965. First published in Dime Detective Magazine. Reprinted by permission of the agents for the author's estate, the Scott Meredith Literary Agency, Inc., 845 Third Avenue, New York, New York 10022.

Gardner, Erie Stanley. Copyright © 1941 by Red Star News Company. Copyright renewed © 1968 by Earl Stanley Gardner. First published in Detective Fiction Weekly Magazine. Used by permission of Jean Gardner for the estate of Earl Stanley Gardner.

Perowne, Barry. Copyright © 1945 by Barry Perowne. Reprinted by permission of A.P. Watt Ltd. Literary Agents.

Arthur, Robert Copyright © 1951 by Robert Arthur. Reprinted by permission of the agents for the author's estate, the Scott Meredith Literary Agency, Inc., 845 Third Avenue, New York, New York 10022.

March, William. Copyright © 1954 by Merchants National Bank of Mobile, Alabama. First published in Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine. Reprinted by permission of Harold Ober Associates, Inc.

Wodhams, Jack. Copyright © 1970 by Conde Nast Publications, Inc. Reprinted by permission of the author and his agents, Cory & Collins. Hoch, Edward D. Copyright © 1971 by Edward D. Hoch. First published in Ellery Queens Mystery Magazine. Reprinted by permission of the author and Larry Sternig Literary Agency.

Pronzini, Bill and Michael Kurland. Copyright © 1975 by H.D.S. Publications, Inc. First published in Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine. Reprinted by permission of the authors.

INTRODUCTION: NO ONE DONE IT

Everyone with a spark of mental agility loves a puzzle. I myself am deficient in puzzle-solving genes (or whatever it is that makes one see a solution) and can never see the ending in a mystery story unless I write the story myself and therefore know the answer to begin with—but I love puzzles all the more for that reason. I love being surprised. I love to get to the answer slowly—slowly—no peeking—not even trying to outguess the author—and then being ravished by the revelation.

No wonder Agatha Christie is by far my favorite mystery writer. Who else can manage to obscure the clues as she could? Who else could hide the solution as neatly? Who else could spring the solution as suddenly and unexpectedly? And whenever I haven't read a particular Agatha Christie for five years or so (there's no such thing as a new one for me, since I have them all and have read them all) I can read it again and be surprised again.

Naturally, the more puzzling a mystery is, the more pleased I am, and since I honestly think I am the most run-of-the-mill person ever invented, and the most nearly average (except, perhaps, for a bit of writing talent) I assume all this is characteristic of everyone.

In that case, since we are all agreed thus far, let us ask ourselves what kind of mystery is the most puzzling and, therefore, the most satisfying. The answer is clear: the one to which there is patently no solution at all.

Let me give you an example from that somewhat complicated and unending variety of mystery tale called scientific research.

There are three ways, and precisely three ways in which the Moon could have come to inhabit our sky as it does; circling the Earth and accompanying our planet in its endless journey about the Sun.

1) The Moon could once have been part of the Earth itself. For some reason, a portion of the Earth broke loose, but that portion, still held by Earth's gravity, won only partial freedom and became the Moon. It has circled Earth ever since and the Earth/Moon relationship is that of mother and daughter.

2) The Moon was never actually part of the Earth itself, but when the original cloud of dust and gas condensed to form Earth, a portion of it condensed about a smaller nucleus and formed the Moon. The two worlds have been associated ever since and the Earth/Moon association is that of brother and sister.

3) The Moon was formed elsewhere in the solar system and was an independent planet to begin with. At some past epoch in Earth's history, however, it was captured. Since then, the two worlds have been associated and the Earth/Moon association is at best, that of cousin and cousin.

Unfortunately, as it happens, strong arguments can be advanced against each of these three theories; so strong that each theory can be ruled out as wrong. Yet there is no natural alternative.

One astronomer, after having considered each hypothesis carefully, pro and con, announced dolefully that the only solution is to suppose that the Moon is simply not there.

Well, of course there is a fourth possibility beyond nature. Astronomers can simply shrug their shoulders and say: "That's how God arranged it."

That, however, is giving up the game, and scientists are not allowed to do that. Somewhere there is an answer that involves only the laws of nature and it will someday be found. That is the scientists' faith. The delight will be in the finding and in the justification of that faith. The fact that it seems an impossible puzzle now will make the eventual delight in the eventual finding all the more intense.

Back, then, to the mystery story proper, the kind with an invented universe that is more orderly and more controllable than the real one; where we will never have to leave the delight of finding to a future generation, but where we need wait only 250 suspense-filled pages at most—and perhaps only 25.

The best puzzle in that case is not merely a mysterious crime but, like the Moon's existence, an impossible one—the kind where the murder takes place in a locked room, or in an unapproachable place, or at a non-existent time, or under conditions when there are no possible suspects.

Here, too, there is always the forbidden possibility: that somehow the solution lies beyond nature.

The true mystery writer is not allowed that solution any more than the scientist is. The universe of the mystery story must be logical. Somewhere, however impossible the crime seems to be, there must be an answer that involves only logic and the natural world. That is the faith of the mystery aficionado. And, again, the delight is in finding the solution and in the justification of that faith.

The closer the mystery writer can come to suggesting the supernatural without falling into the pit, the better. The more forcefully he pushes the reader into despair, the greater the reader's delight at finding the universe of logic intact and unharmed.

The history of impossible crimes is just about coeval with the history of the mystery story.

The very first of the modern mystery stories, complete with talented amateur detective, and untalented bosom buddy, was The Murders in the Rue Morgue by Edgar Allan Poe, published in 1841, and, behold, it was an impossible crime!

The Sherlock Holmes story which most aficionados would agree was the best (and Conan Doyle himself agreed) is The Adventure of the Speckled Band and, behold, it, too, was an impossible crime!

One of Agatha Christie's closest rivals for my undying love is John Dickson Carr, and, indeed, impossible crime novels were his specialty. (What a pity we don't have room in the book for one of his novelsl)

Well, confining ourselves to shorter pieces, we still have a long collection of impossible crimes for your delectation and delight. Read on!

Edgar Allan Poe

Soldier, literary critic, editor, poet, and short story writer, Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849) accomplished a great deal during his relatively brief life, even though he was an essentially tragic and self-destructive figure who drank himself to death. He popularized science fiction and psychological terror and invented the detective story in 1841 with "The Murders in the Rue Morgue." This brilliant story also introduced the first locked room detective story and the first series detective, Auguste Dupin. Ironically, however, it has never appeared in a locked room anthology until now.