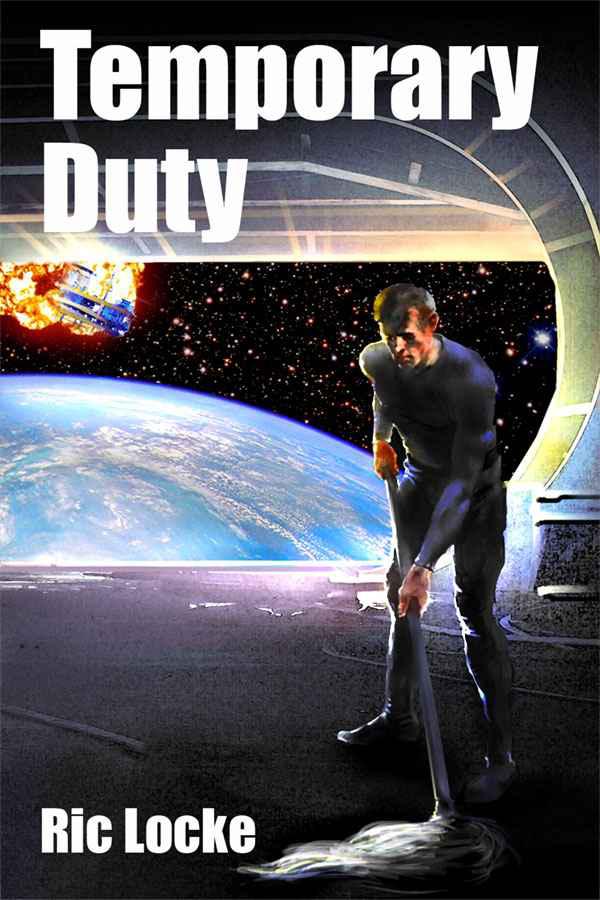

Temporary Duty

Authors: Ric Locke

by

Ric Locke

Copyright © 2010, 2011 by Warrick M. Locke. All rights reserved.

"Thar ’tis, I reckon," John Peters said, his West Virginia accent thicker and further back in the woods than normal. A point of light, brighter than the sliver of waning moon, moved slowly across the sky. It was big enough for a person of normal eyesight to see that it was an object longer than it was wide.

Kevin Todd followed Peters’s gaze. "I still can’t quite believe it," he breathed. "TDY to outer space. Peters, you’ve got a gift for timing."

The spaceship–a real alien spaceship with real live aliens aboard, right out of the vids–had appeared in the sky last February, and a delegation from it had dropped in on USS

Barack H. Obama, Jr.

on station in the eastern Med.

Barry-O

had been at flight ops at the time, and according to scuttlebutt a fine, exciting, and memorable time had been had by all. The net had been full of it–first contact with nonhuman intelligence, opportunity for the human race, all of that–but lately the coverage had tapered off, talking heads mentioning briefly that negotiations weren’t going well, in mournful tones between the disaster clips.

"TAD, more like," Peters commented. "Our orders say report to–hang on, somethin’s happening."

A smaller spark had detached itself from the big one and was moving faster, preceding its mothership across the sky. It had to be the aliens’ landing craft. The amazing thing wasn’t that it made a McDonnel-Mikoyan F37 look like a dugout canoe; the amazing thing was that a couple of enlisted sailors–Peters was an E5 or Second Class, Todd an E4 or Third Class–would be riding it into the sky in a couple of hours.

"We need to be getting our shit together," Todd commented. Peters grunted assent, and the two of them turned to walk across the flight deck. A cold front had come through on Saturday, bringing sapphire-clear skies and a sharp drop in temperature, not usual for mid-November in North Florida, and the sailors puffed a little, their breath condensing in the chill air.

"Meet you at the brow in half an hour," Peters suggested.

"You say it," Todd half-agreed, and the two separated to fetch their seabags. USS

William J. Clinton

was a near-permanent fixture at Mayport Naval Station, running on shore power and a minimum of that, and at 0400 on a Monday morning most lights were out and few were stirring. They followed a path marked in yellow glowtape through the gloom of the empty hangar deck, showed their ID and orders to a First Class who didn’t give a damn, and stopped at the head of the brow to render honors. Then they humped their seabags down the gangway, each looking back in glances that turned furtive when the other caught him at it.

"Just another transfer," Peters advised with determined heartiness.

"You say it," Todd acknowledged.

In the first flush of optimism an enterprising squadron commander aboard the

Obama

had made a deal: a couple of squadrons of Navy planes were to go on the aliens’ next voyage, showing what Earth and humans could do. No other agreement of any type had been reached, and the prospects seemed remote, but for some reason the aliens considered their deal with Commander Harlan Bolton, CO VF22, done; the Government had reluctantly allowed the Navy to go along with the gag, hoping to salvage something.

The planes would have to be refitted–jet engines need air, which is in short supply in space–and the Navy wasn’t willing to sacrifice modern equipment to drastic modification. A small crew of the aliens were out in Arizona, picking equipment to use and installing spaceship engines in it when they weren’t tripping over diplomats and FedSec goons. The aircraft would also need support, as would the officers flying them, and here the aliens had balked, citing space restrictions. The compromise eventually reached was that two hundred sailors, a ridiculously skeletonized crew, would go; volunteers had been asked for, and the resulting stampede cherrypicked.

Then the aliens, who called themselves Grallt, had asked for one more thing. The Navy had reluctantly agreed, and John Peters had been in the right place at the right time.

* * *

A sentry stopped them, M27 at the ready, and they dumped their seabags on the grass and reached for ID blocks as he grounded arms. The Marine gave the blocks a cursory inspection. "All right, you can wait here," he said, indicating a patch of grass no different from any other in the vicinity. "How do you swabbies rate this?"

"Advance detail," Peters explained shortly. "Menial labor, it says here. The main detachment’ll be comin’ up after Thanksgiving."

The Marine’s face was invisible behind his faceplate, but his voice was amused. "Mops and dusting. You volunteered?"

"Wouldn’t you’ve?" Peters gestured, a thumbs-up toward the sky.

"Ass up, and bare if necessary. I’m good at toilets, by the way."

"I’ll put in a word."

There was still no gray in the eastern sky when a light-colored shape ghosted overhead, coasting impossibly to a stop over the field and dropping with no sound but a faint thump. Its nose was toward them, pointing slightly to their left, and light shone from cockpit windows and a row of ports down the side. It looked a bit like the old Space Shuttle, except for the windows and not having black on the belly. Peters shared a look with Todd, thinking foolishly,

It ain’t all that big!

Todd’s eyes were wide.

"Looks like your ride’s here," said the sentry. "Good trip."

"Thanks," Peters said, and they shouldered their seabags and trudged that way.

As they got closer to the machine it looked less and less familiar, like its owners, who could easily pass for human until you could see their faces. It sat impossibly low, its landing gear invisible below wings that curved more than the human version’s did. There was no door or hatch on this side; they walked around the port wing toward the tail, finding that the wingtip came just about to eye level on Peters. On the wingtip was a transparent bubble, maybe a running light but who the Hell knew, mounted on a flange with cross-slotted screws.

Hell. Not cross-slotted screws.

Trefoil

-slotted screws.

A welcoming delegation was hurrying up from the Admin buildings, headed by Captain Van Truong, the base commander, and a glittering officer who had to be Commander, Surface Fleet Atlantic. A small group of other officers and a loose gaggle of civilians in the bright-colored anoraks issued to visitors followed. Peters slung his seabag and approached the group with a snappy salute. "Good mornin’, sir," he said to the admiral, and Todd followed suit a few beats later.

The return salute was crisp, not the negligent wave usual in somebody with so exalted a rank. "At ease," the admiral said. "You must be the men they requested for help in setting up."

"Yes, sir," said Peters.

"Enlisted people," said Captain Van Truong. "Junior enlisted people." He sounded disgusted and angry, which was more what Peters and Todd had expected.

"That’s what they asked for," the admiral said mildly. "Insisted on, in fact. Sailor, how did you end up with this assignment?"

"Dumb luck, sir," Peters told him. "I happened to be on the phone to my detailer when the request come up on the computer."

The admiral suppressed a grin, shook his head, and started to say something else, but was interrupted by the appearance of a Grallt. It–he?–stepped lightly down off the wing and came over. "Pleasant greetings," he said, raising his left arm in an open-palmed salute, probably not aware that he was continuing a long tradition begun by Michael Rennie.

The admiral responded with another crisp salute. "Good morning, Ambassador Dreelig," he said. "Welcome to Mayport Naval Station. May I introduce my colleagues?"

"In a moment," said the Ambassador. "First, which of you are John Peters and Kevin Todd?" The two sailors stepped forward. "Ah. Pleasant greetings. You have your belongings? Yes, I see that you do. Please go aboard and, ah, report to Pilot Gell. He will show you what to do."

"Aye, aye, sir," said Peters, and saluted. The Ambassador seemed a bit confused, but raised his left arm again.

"By your leave, sir," Peters said to the admiral, maintaining protocol.

"Carry on," the admiral granted, and the sailors slung their seabags up on the wing and climbed the step, using the straps to drag them the few meters to the hatch.

Their first and continuing impression of the Grallt shuttle was that it could have been built in Seattle or Moscow–or Grenoble for that matter; it certainly looked old enough. A section covered with ordinary-looking black nonskid had separated from the–flaps? ailerons?–to form steps up to the waist-high upper surface, and more of the black stuff made a walkway to the entry, which was a curved hatch four meters or so forward of the trailing edge. Inside, seating was two and two across, a little bulkier than Boeing usually supplied, covered in blue plush worn shiny in places, with pale tan padding showing through occasional tears. Two parallel strips of bluish lights extended forward over the aisle, ending at a bulkhead with a closed door. There was nobody visible.

"So where’s this Pilot Gell?" Todd asked.

Peters shrugged. "I reckon he’s up front, where a pilot belongs. My question is, what do we do with the seabags? I’m a little tired of carryin’ the damn thing."

Another door led aft. Todd tried it: locked. "I guess we hump ‘em a little further."

"Reckon so."

Beyond the forward door was a smaller compartment with only eight seats, larger, one on each side. "Officers’ country," Peters guessed. Another door led to a short corridor, then to four chairs set two and two, upholstered in black, as big as the "officers’" but somehow more businesslike. In front of the first pair was the instrument panel, with the windshield above and big rectangular ports by each of the seats. The panel sloped rather than being vertical like an airplane’s, and was bare of screens and flashing lights, almost bare period. Both were familiar with aircraft instruments, and both found it a bit puzzling that a spaceship–a

spaceship

, for God’s sake–should have controls that looked not much more complex than those on a ten-meter liberty launch.

An individual, probably "Pilot Gell," sat in the right front seat, and turned his head at their entry. He had two eyes arranged frontally, sandy-brown head hair parted on the left, and a pair of ears in more or less the regulation position, but that was where the similarities ended. Instead of anything like a nose he had a long cleft, beginning between the eyes and spreading at the bottom into an inverted Y that formed his upper lip, and his jaw was slightly wider and less pointed than the norm for human beings. The ambassador had worn their version of a mustache, two bands of silky hair beginning just below the inside corners of the eyes and extending vertically down to the upper lip; Gell was clean-shaven, which made the two of them easy to distinguish, even by the uninitiated. He was wearing a one-piece garment like a jumpsuit, off-white with splashes of bright reds and yellows in no discernible pattern.

The pilot said something incomprehensible; when the sailors didn’t respond he stood, pushed by them, opened one of the portside doors, and made a choppy gesture, indicating the cabinet. They slung their seabags inside and Gell closed the door, tested the latch by yanking on it, nodded, and pushed by them again. Up close, he had a slight odor, musty and unfamiliar but not unpleasant. He took his seat and indicated the other chairs with a wave.

Peters got the front seat, partly by being senior and partly by pushing. From there the sparseness of the instrument panel was even more remarkable: a couple of dials with white-on-black crosses in the middle and squiggles around the periphery, a couple more that were old-fashioned meters with needles, and half a dozen things an inch in diameter with engraved squiggles above and below, probably push buttons. A rod protruded from a complicated set of concentric fittings below the left-hand dial, ending in an arrowhead fifteen centimeters across and half that thick, with its point embedded in another complex joint. The arrowhead was convenient to Peters’s left hand, but when he started to touch it Gell said something short and definite, and shook his head.

They sat and waited. Outside the front transparency the sky got brighter, an utterly atypical perfectly clear day. There was nothing to do, and it was warm; first Peters, then Todd, peeled off their peacoats and stuffed them in the locker. They took care not to get too close to anything that looked like a control, and Gell busied himself reading meters and making left-handed notes on a pad of paper, occasionally pushing something or grunting.

Todd tapped Peters on the shoulder. "Look here," he said. "This tab on the arm. Betcha it makes the seat recline, see?"

Peters found a similar control on his own chair-arm. "Gell," he said softly. When the pilot looked up he said, "OK?" and fingered the tab. Gell nodded vigorously and went back to his business, and Peters pushed the tab, finding that it indeed reclined the chair with a soft electric-motor whine. Further manipulation changed the shape of the seat in other ways, some of them nonsensical until he remembered that it wasn’t built for humans. He twiddled until he found a comfortable position and leaned back. Despite the strangeness of the situation, warmth, idleness, and a long sleepless night did their work.