Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh (9 page)

Read Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh Online

Authors: John Lahr

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Literary

BOOK: Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh

3.76Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Thanks to the dread of the physical that Edwina “imposed,” Tennessee, Rose, and Dakin were strangers to their own bodies. Dakin remained sexually inexperienced until his marriage at the age of thirty-seven; Rose, whose first signs of madness, according to a 1937 Farmington State Hospital report, were a “reaction to delusions of sexual immorality of family,” died a virgin; and, by his own admission, Williams didn’t masturbate until he was twenty-six, “and then not with my hands but by rubbing my groin against my bed-sheets while recalling the incredible grace and beauty of a boy-diver plunging naked from the high board in the swimming-pool of Washington U. in St. Louis.”

In

The Glass Menagerie

, Laura’s desire—for her gentleman caller, Jim O’Connor, on whom she had a secret high-school crush—paralyzes her; she literally can’t bring herself to stand and to answer the front door. In the Williams family, the fear of showing desire made the “highly sexed” Rose hunch her narrow shoulders in the presence of the opposite sex and “talk with an almost hysterical animation which few young men knew how to take.” “She made no positive motion toward the world but stood at the edge of the water, so to speak, with feet that anticipated too much cold to move,” Williams writes in “Portrait of a Girl in Glass,” his first portrayal of Laura, whose gimp leg stands in for Rose’s psychological disability. Williams had his own form of morbid shyness. Having begun early on “to associate the sensual with the impure, an error that tortured me during and after pubescence,” he found it “almost entirely impossible . . . to speak aloud in class.” Anything that promised exposure both excited and confounded him. “Almost without remission for the next four or five years, I would blush whenever a pair of human eyes, male or female (but mostly female since my life was spent mostly among members of that gender) would meet mine,” he wrote in his memoir. It was a shyness that persisted for years. “What taunts me worst is my inability to make contact with the people, the world,” Williams wrote in a 1942 diary entry. “I remain one and separate among them. My tongue is locked. I float among them in a private dream and shyness forbids speech and union.”

The Glass Menagerie

, Laura’s desire—for her gentleman caller, Jim O’Connor, on whom she had a secret high-school crush—paralyzes her; she literally can’t bring herself to stand and to answer the front door. In the Williams family, the fear of showing desire made the “highly sexed” Rose hunch her narrow shoulders in the presence of the opposite sex and “talk with an almost hysterical animation which few young men knew how to take.” “She made no positive motion toward the world but stood at the edge of the water, so to speak, with feet that anticipated too much cold to move,” Williams writes in “Portrait of a Girl in Glass,” his first portrayal of Laura, whose gimp leg stands in for Rose’s psychological disability. Williams had his own form of morbid shyness. Having begun early on “to associate the sensual with the impure, an error that tortured me during and after pubescence,” he found it “almost entirely impossible . . . to speak aloud in class.” Anything that promised exposure both excited and confounded him. “Almost without remission for the next four or five years, I would blush whenever a pair of human eyes, male or female (but mostly female since my life was spent mostly among members of that gender) would meet mine,” he wrote in his memoir. It was a shyness that persisted for years. “What taunts me worst is my inability to make contact with the people, the world,” Williams wrote in a 1942 diary entry. “I remain one and separate among them. My tongue is locked. I float among them in a private dream and shyness forbids speech and union.”

Edwina, who once boasted that “the only psychiatrist in whom I believe is our Lord,” was, according to Williams, “essentially more psychotic than my sister Rose.” “Like a force of nature, she seemed to be directed blindly,” Williams said. Her paranoia and her terror lodged in her children, modifying their behavior and keeping them at once overly suggestible and under wraps. Like Amanda, she used her children as vessels into which she emptied the desires and the fears of her frustrated heart. “You’re my right-hand bower! Don’t fall down, don’t fail!” Amanda exhorts her idealized son. For a long time, Williams and Rose struggled to maintain their image as dutiful, well-mannered representations of their mother’s hopes. Rose, in Edwina’s romantic fantasy, was a Southern belle and wife-to-be. Likewise, in the first beats of

The Glass Menagerie

, Amanda orders the crippled dateless Laura to sit: “Resume your seat, little sister—I want you to stay fresh and pretty—for gentleman callers!” “I’m not expecting any gentleman callers,” Laura says, who knows her disability debars her from a normal life. “But Mother—,” she says. “I’m—crippled!” Amanda refuses to acknowledge even the most glaring fact of Laura’s damage. “Nonsense! Laura, I’ve told you never, never to use that word. Why, you’re not crippled, you just have a little defect—hardly noticeable, even!” she says. Before Laura’s eyes and ours, Amanda fictionalizes the world and insists that her children deny the truth of their very essence.

The Glass Menagerie

, Amanda orders the crippled dateless Laura to sit: “Resume your seat, little sister—I want you to stay fresh and pretty—for gentleman callers!” “I’m not expecting any gentleman callers,” Laura says, who knows her disability debars her from a normal life. “But Mother—,” she says. “I’m—crippled!” Amanda refuses to acknowledge even the most glaring fact of Laura’s damage. “Nonsense! Laura, I’ve told you never, never to use that word. Why, you’re not crippled, you just have a little defect—hardly noticeable, even!” she says. Before Laura’s eyes and ours, Amanda fictionalizes the world and insists that her children deny the truth of their very essence.

AMANDA: It’s almost time for our gentleman callers to start arriving. (

She flounces girlishly toward the kitchenette

.) How many do you suppose we’re going to entertain this afternoon? . . .

LAURA: (

alone in the dining room

) I don’t believe we’re going to receive any, Mother.

AMANDA: (

reappearing, airily

) What? No one—not one? You must be joking!

(

LAURA nervously echoes her laugh.

. . .)

For her first-born son, Edwina’s desires were especially strong. “My mother was extremely, overly I would say, affectionate toward my brother,” Dakin Williams said. With CC permanently struck from her emotional map, Edwina formed a marriage of sorts with young Tom. “Her husband had deserted her shortly after S. was born,” Williams wrote in the short story that preceded the 1945 play

Stairs to the Roof

. “She was determined the boy should not escape from her too.” From the day she bought her chronically shy twelve-year-old son a ten-dollar typewriter, Williams was, in her mind, “mah writin’ son,” joined to her apron strings by a shared fantasy of self, a sort of grandiose co-production that became his destiny. “Within a few months,” Williams wrote to Elia Kazan, writing “became the center of my life . . . then all of a sudden one day when I sat down at the second-hand (maroon-colored) Underwood portable that I had received for Xmas . . . it suddenly occurred to me: this is my life, this is my love! What will I do if I LOSE it?—And the thought struck such terror in my heart, that for—I forget the exact intervals of time—days, weeks!—I was not able to write. I was a blocked artist!”

Stairs to the Roof

. “She was determined the boy should not escape from her too.” From the day she bought her chronically shy twelve-year-old son a ten-dollar typewriter, Williams was, in her mind, “mah writin’ son,” joined to her apron strings by a shared fantasy of self, a sort of grandiose co-production that became his destiny. “Within a few months,” Williams wrote to Elia Kazan, writing “became the center of my life . . . then all of a sudden one day when I sat down at the second-hand (maroon-colored) Underwood portable that I had received for Xmas . . . it suddenly occurred to me: this is my life, this is my love! What will I do if I LOSE it?—And the thought struck such terror in my heart, that for—I forget the exact intervals of time—days, weeks!—I was not able to write. I was a blocked artist!”

In a real sense, Williams the writer was dreamed up by the disappointed Edwina. Writing strengthened his bond with his mother at the same time that it provided Edwina with yet another soldier in her battle against the disdained and disdainful CC, who, as Dakin said, “thought writers were complete zeroes who would never amount to anything, i.e. make money.” “I feel uncomfortable in the house with Dad, when I know he thinks I’m a hopeless loafer,” Williams wrote. As Cornelius spurned Tom’s efforts, Edwina “doubled her support,” Lyle Leverich writes in

Tom

. “Whether intentionally or not, she had fashioned a vengeful weapon that served as a permanent wedge between father and son.” For Williams, storytelling became a kind of collusion, an attempt to live up to his mother’s vivacity, her way of imagining, and her sense of him. The burden of the roles the children inhabited finally became insupportable.

Tom

. “Whether intentionally or not, she had fashioned a vengeful weapon that served as a permanent wedge between father and son.” For Williams, storytelling became a kind of collusion, an attempt to live up to his mother’s vivacity, her way of imagining, and her sense of him. The burden of the roles the children inhabited finally became insupportable.

Unacknowledged by CC and reconstituted by Edwina—the unspoken family message was “you cannot have the feelings you have”—the children struggled to make a place in their lives for their own emotional reality. The combination of CC’s violence and Edwina’s repression was at the root of Williams’s various physical complaints, and of his breakdown at the International Shoe Company in 1935. “I was a sweet child. Child murdered,” he wrote in his journals. The horrible family atmosphere was also a recipe for madness. According to Williams, Rose had “the same precarious balance of nerves that I have to live with” but no outlet for them; gradually, and inexorably, she descended into her own unreachable world. One of her reported “delusions,” she told one of her doctors, was that “all of the family were mentally deranged.” After Rose’s first breakdown, Williams recalled her walking into his tiny room “like a somnambulist” and announcing “we must all die together.” A psychiatrist told CC, “Rose is liable to go down and get a butcher knife one night and cut your throat.” “Tragedy. I write that word knowing the full meaning of it,” Williams wrote in his journal on January 25, 1937. “We have had no deaths in our family but slowly by degrees something was happening much uglier and more terrible than death.”

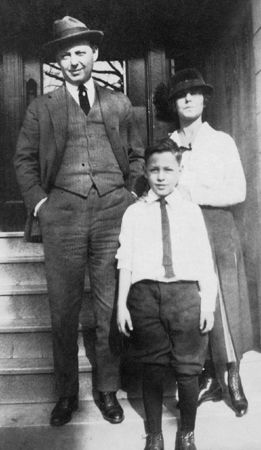

With father and mother

When the disoriented and delusional Rose was first admitted to the Farmington State Hospital, at the age of twenty-eight, the psychiatrist who debriefed her observed, “Insight was entirely absent although she at times states that she is mentally ill as a result of her family’s troubles.” In Williams’s eyes, Rose’s lobotomy was, to some degree, a result of Edwina’s sexual hysteria, an enforcement of radical innocence through the surgical removal of the part of the brain that remembers. “Mother chose to have Rose’s lobotomy done. My father didn’t want it. In fact he cried. It’s the only time I saw him cry,” Williams said. “Why was the operation performed? Well, Miss Rose expressed herself with great eloquence, but she said things that shocked Mother. Rose loved to shock Mother.” He went on, “Rose said, ‘Mother, you know we girls at All Saints College, we used to abuse ourselves with altar candles we stole from the Chapel.’ And Mother screamed like a peacock! She rushed to the head doctor, and she said, ‘Do anything,

anything

to shut her up.’ ” The lobotomy was a family tragedy; it finally and forever fit Rose into Edwina’s version of life. Rose, as Edwina wrote, “now lived in a world where she remembers only the good things.”

anything

to shut her up.’ ” The lobotomy was a family tragedy; it finally and forever fit Rose into Edwina’s version of life. Rose, as Edwina wrote, “now lived in a world where she remembers only the good things.”

Where Rose was forced to comply, Williams escaped, mostly into his writing, in which he was able to turn himself and the torture of his family into an event of a different kind. In playwriting, he found a strategy both to hide himself away and to vent his murderous feelings. On the stage, he could exorcise his anger. Writing, he said, was an act of “outer oblivion and inner violence.” He likened his lyrical impulses—what he called his “sidewalk histrionics”—to the performance of a little Southern girl he once saw, decked out in “cast-off finery,” who screamed to her indifferent friends, “Look at me, look at me, look at me!” until she fell over in “a great howling tangle of soiled white satin and torn pink net. And still nobody looked at her.” (Williams’s first story, “Isolated”—published in

Junior Life

at five cents a copy—was a three-paragraph fantasy about a flood that leaves him marooned and invisible until he is saved by a search party that is “reclaiming dead bodies.”) Rose, who had no symbolic release for her rage, took it out on herself and her family. The lobotomy was the reverse of her brother’s solution: outer violence and inner oblivion. According to her psychiatric report prior to the lobotomy, Rose suffered from “somatic delusions: felt her heart was as big as her chest; thought that her body had disappeared from her bed.” The lobotomy transformed her literally into a ghost of her former self.

Junior Life

at five cents a copy—was a three-paragraph fantasy about a flood that leaves him marooned and invisible until he is saved by a search party that is “reclaiming dead bodies.”) Rose, who had no symbolic release for her rage, took it out on herself and her family. The lobotomy was the reverse of her brother’s solution: outer violence and inner oblivion. According to her psychiatric report prior to the lobotomy, Rose suffered from “somatic delusions: felt her heart was as big as her chest; thought that her body had disappeared from her bed.” The lobotomy transformed her literally into a ghost of her former self.

That ghostliness is built into

The Glass Menagerie

, in which shards of memory play out the Narrator’s internal drama. By standing outside the scene, the Narrator suggests both his and Williams’s detachment, which verges on the spectral. Absence dominates the play. A specially lit photograph of the Wingfields’ missing father in his First World War uniform stands on the Wingfield mantelpiece, serving as a reminder—as if one were needed—of the omnipresent weight of CC’s abandonment: the grief that punished and unhinged the Williams family. Tom Wingfield—like the young Williams, whose depressions he described as “interior storms that show remarkably little from the outside” and which created “a deep chasm between myself and all other people”—feels himself to be, if not a ghost, then not exactly alive. “You know it don’t take much intelligence to get yourself into a nailed-up coffin,” he says. Tom’s habitual moviegoing, which so mystifies Amanda, is no mystery to him. “People go to the movies instead of moving!” he explains. Psychic survival is linked to make-believe.

The Glass Menagerie

, in which shards of memory play out the Narrator’s internal drama. By standing outside the scene, the Narrator suggests both his and Williams’s detachment, which verges on the spectral. Absence dominates the play. A specially lit photograph of the Wingfields’ missing father in his First World War uniform stands on the Wingfield mantelpiece, serving as a reminder—as if one were needed—of the omnipresent weight of CC’s abandonment: the grief that punished and unhinged the Williams family. Tom Wingfield—like the young Williams, whose depressions he described as “interior storms that show remarkably little from the outside” and which created “a deep chasm between myself and all other people”—feels himself to be, if not a ghost, then not exactly alive. “You know it don’t take much intelligence to get yourself into a nailed-up coffin,” he says. Tom’s habitual moviegoing, which so mystifies Amanda, is no mystery to him. “People go to the movies instead of moving!” he explains. Psychic survival is linked to make-believe.

At the finale, the Narrator stands before the audience as a haunted man, hounded by figments of his internal world. “I traveled around a great deal,” he says. “The cities swept about me like dead leaves, leaves that were brightly colored but torn away from the branches. I would have stopped, but I was pursued by something[. . . .] Then all at once my sister touches my shoulder. I turn around and look into her eyes . . . Oh, Laura, Laura, I tried to leave you behind me, but I am more faithful than I intended to be!” The Narrator stands in a spotlight, bathed in white light—the light of the imagination.

In the first moment of the play, the Narrator announces the “tricks up his sleeve”; in the last beats, he shows how, through the act of storytelling and artifice, he has taken command of himself. The stage becomes “almost dancelike,” a hallucinatory tableau vivant in which Williams transforms what he called “my doomed family” into a form of glory. The panoply of his recollected misery becomes a dumb show—an “interior pantomime,” the stage directions call it: “The interior scene is played as though viewed through soundproof glass. Amanda appears to be making a comforting speech to Laura who is huddled upon the sofa. Now that we cannot hear the mother’s speech, her silliness is gone and she has dignity and tragic beauty. Laura’s dark hair hides her face until at the end of the speech she lifts it to smile at her mother. . . . Amanda’s gestures are slow and graceful . . . as she comforts the daughter.” Instead of being overwhelmed by the memories of family madness, the Narrator is now in control of his own internal turmoil. “Blow out your candles, Laura—and so good-bye,” he says, in the last line of the play. Laura does as she’s told. The silent final gesture demonstrates the Narrator’s dramatic prowess; it also broadcasts Williams’s dramatic goal—to redeem life, through beauty, from the humiliation of grief.

When the final curtain came down on the Broadway opening of

The Glass Menagerie

, the audience knew that some kind of theater history had been made. “Never before in my experience or never since and perhaps never again in my life will there be anything like it,” Eddie Dowling said. “It was really a thunderous, thunderous thing.” The cast took twenty-four curtain calls. Laurette Taylor, “holding out the ruffles of the ancient blue taffeta as though she might break again into the waltz of her girlhood,” was crying. “All the people backstage were crying,” recalled the actress Betsy Blair, who was Julie Haydon’s understudy. For the first time that year, a Broadway audience rose to its feet shouting, “Author, Author!” The calls persisted until Williams was coaxed out of his seat. With a helping hand from Dowling, he climbed up onto the stage. The audience experienced Williams’s childhood just as he had—startled, bewildered, terrified, and excited. Now, as he stood before the boisterous crowd, he even seemed jejune. Slight, his hair closely cropped, his jacket button missing, the blushing author bowed awkwardly to the actors; in so doing, he showed his backside to the audience.

The Glass Menagerie

, the audience knew that some kind of theater history had been made. “Never before in my experience or never since and perhaps never again in my life will there be anything like it,” Eddie Dowling said. “It was really a thunderous, thunderous thing.” The cast took twenty-four curtain calls. Laurette Taylor, “holding out the ruffles of the ancient blue taffeta as though she might break again into the waltz of her girlhood,” was crying. “All the people backstage were crying,” recalled the actress Betsy Blair, who was Julie Haydon’s understudy. For the first time that year, a Broadway audience rose to its feet shouting, “Author, Author!” The calls persisted until Williams was coaxed out of his seat. With a helping hand from Dowling, he climbed up onto the stage. The audience experienced Williams’s childhood just as he had—startled, bewildered, terrified, and excited. Now, as he stood before the boisterous crowd, he even seemed jejune. Slight, his hair closely cropped, his jacket button missing, the blushing author bowed awkwardly to the actors; in so doing, he showed his backside to the audience.

Other books

Mad Worlds Collide by Tony Teora

Promises (Book One of The Syrenka Series) by Amber Garr

WrappedAroundYourFinger by Fallon Blake

And To Hold: Vampire Assassin League #20 by Jackie Ivie

Sliver of Silver (Blushing Death) by Sabol, Suzanne M.

I'm Your Man by Timothy James Beck

Under Witch Curse (Moon Shadow Series) by Maria Schneider

A Tale of Two Pretties by Lisi Harrison

Based: A Stepbrother Romance (Extreme Sports Alphas) by Hamel, B. B.

Stuart Little by E. B. White, Garth Williams