Teutonic Knights (9 page)

Authors: William Urban

Tags: #History, #Non-Fiction, #Medieval, #Germany, #Baltic States

At this time a papal legate, Bishop William of Modena, was in Prussia. This Italian prelate was well acquainted with Baltic affairs, having previously served in Livonia and Estonia. He had just come from Denmark, where he had been discussing the disordered affairs of the Livonian Crusade with King Waldemar II. Thence he had sailed to Prussia, and was present from the late autumn of 1228 (or early spring of 1229) until shortly before January 1230, when he seems to have been in Italy, conferring with Hermann von Salza.

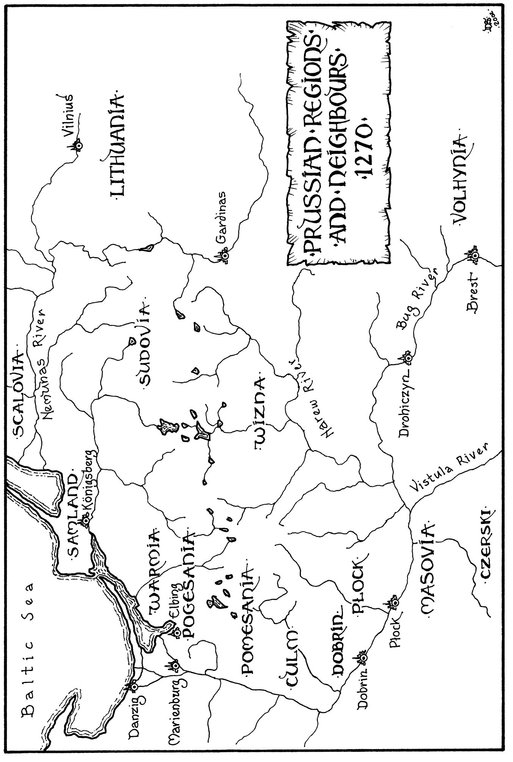

Information about the legate’s activity is scanty. He translated a grammar book into the Prussian language so that the natives could learn to read, and he made a few converts, apparently among the Pomesanians and Pogesanians north of Culm. It is very likely that the new converts mentioned in papal documents of 1231 and 1232, whom the Teutonic Knights were warned against disturbing, refer to those Prussian Christians, and not to the crusaders in Livonia as some modern historians have assumed. William of Modena was always very concerned about the well-being of converts. He feared that ill-treatment would cause them to believe that all Christians were hypocrites and tyrants, whereas Christianity should bring a greater amount of peace, justice, and fairness than existed before, in addition to the benefits of spiritual consolation and eternal life.

William of Modena was also determined to co-ordinate the crusading efforts of regional powers which might otherwise spend more time and effort frustrating one another than in prosecuting the holy war. It is at this time, in January 1230, that documents from Count Conrad and Bishop Christian were obtained (or recreated, or falsified), an action that complicated immensely subsequent efforts to understand what had been promised to the Teutonic Order and when the promises were made. Later generations, unable to call up the dead for personal testimony, relied on their instincts, basing their judgements more upon their current political interests than any determination to find the truth.

Whatever success William of Modena had, it fell short of discouraging the Teutonic Knights from continuing their attacks on settlements in Culm. Until this time the Teutonic Knights had raided across the great river but had not tried to establish themselves there. This was the era of reconnaissance. Quite literally, that meant getting to know the land and the people. The handful of knights and sergeants were learning the language, the customs, and the military tactics of their opponents, preparing for the day when reinforcements would arrive.

In 1230 reinforcements under the command of Master Hermann Balk rode into Vogelsang. A capable warrior who was to lead the crusade in Prussia and Livonia for many years, Balk was a reasonable, conciliatory man in every respect except one – when dealing with pagans or infidels, he had no tolerance, patience, or mercy. Among Christians of any kind – German, Polish, Prussian – he seems to have been respected and trusted. The traditions he established were upheld in their essentials for the rest of the century, right down to the master’s seal depicting the flight of the Holy Family into Egypt. Perhaps symbolising Balk’s pre-eminence, his was the only master’s seal to bear his name. All others were anonymous.

Hermann von Salza had been able to send this party of knights because he was at last free from his extraordinary commitments in the Holy Land. Although he now had greater responsibilities there than before the imperial crusade, a truce was in effect and the usual number of troops was not required. If enlistments remained at the present high level, he could expect to send more troops to Prussia every year without diminishing the garrisons around Acre. Moreover, there was still some small hope that the Teutonic Order would be able to return to Hungary, a move that would limit the involvement in Prussia. Pope Gregory IX was writing to King Bela, asking him to return the confiscated lands. But Hermann von Salza was a realist. While he did not expect to get the Transylvanian lands back, he knew that God had strange ways – kings changed their minds, they got into unexpected troubles, and they died. Hermann von Salza was ready to go back to Hungary if God should put the opportunity before him again.

Prussia was a different matter, exciting in its possibilities and challenging in its difficulties, but much preparation and hard work would be necessary and time would pass before results could be expected. The grand master could not send in more than a handful of knights until supplies were built up to feed more troops, and until castles were constructed to protect and house them. It was a matter of careful administration to send just the right number of men at the right time and thereby make the best use of the slender resources that Hermann von Salza had available for his operations everywhere – in the Holy Land and Armenia, in Italy, and in Germany. Prussia came last in his estimation.

Hermann Balk went first to the problem that had so bothered the leaders of the order for two years – the grant by which Duke Conrad had given them lands for their maintenance. Culm was occupied by the enemy, so the Prussian master would somehow have to find his own means of financing the campaigns to subdue the pagans. This was understandable. What he could not agree to was that after Culm was occupied it would still belong to Bishop Christian and Duke Conrad. In short, what was in it for the Teutonic Knights, who would presumably have to remain in Culm to defend it from the other Prussians? Balk, therefore, went to the duke and bishop and apparently confronted them with the story of the order’s Hungarian debacle. He had brought an army and was ready to use it to protect them, their lands, and their subjects, but the duke and his bishop had to be ready to pay the price. He requested (politely surely, but certainly firmly) a grant of sovereignty more similar to that granted by the emperor in the Golden Bull of Rimini in 1226 than that which they had proposed. What he got has been the subject of dispute between German and Polish historians ever since, but whatever the exact terms, the grant was sufficient to satisfy him, the grand master, and the grand chapter meetings that discussed it.

Relatively quickly crusader armies composed of Germans, Poles, Pomerellians and native militias overran the western Prussian tribes. As many as 10,000 men took the cross in the summer of 1233, perhaps inspired by the opportunity to see a piece of the true cross, and built the fortress at Marienwerder in the middle of Pomesania, on a tributary of the Vistula, about half-way between Thorn and the sea; that winter those crusaders who had stayed were joined by Dukes Sventopełk and Sambor of Pomerellia for an invasion of Pogesania. When the pagans came out in a phalanx to meet the crusaders on the frozen surface of the Sirgune River, they were quickly panicked by the appearance of the Pomerellian cavalry in their rear; the effort to flee became a massacre.

The count of Meissen was important in the great offensive of 1236 – 7. First he built large sailing ships, then sank the small pagan vessels that came out to challenge him, and finally he transported his men downstream to strike in the enemy’s rear. The Pogesanian militia came out to fight, but fled after hearing the count’s men blowing horns (presumably in their rear). Clearly, the Prussians were in no mood to stand up to heavy cavalry, flights of crossbow quarrels, and disciplined infantry. Western methods of making war swept the Prussians from level battlefields. It was harder to find the pagans in the woods and swamps, especially in the summer, but in winter – a season of war in which the crusaders came to specialise – they could be easily traced back to their lairs.

Each year small crusader armies came to Prussia, and each year the result was the same – an expansion of the order’s conquests. Many of these volunteers were Polish, and everyone involved in this crusade understood that without the steadfast support of the Piast and Pomerellian dukes the volunteers who came from Germany could have done little besides provide garrisons for the castles already constructed. Why, then, if the Poles were doing so much of the fighting, were the Teutonic Knights so important?

The answer is that Polish and Pomerellian crusaders went home or stayed home. At first they were only gone from the onset of bad weather in the fall until the long days of the short summer began, but within a few years their active contributions went permanently missing – Duke Conrad had troubles on his other frontiers, Duke Sventopełk was quarrelling with his brothers, and eventually all the Piasts of Poland were feuding. None of these feudal lords, nor their bishops, had the resources to provide an occupation force – that became the role of the Teutonic Knights here just as it had been in the Holy Land. Celibate knights, pledged to poverty and obedience, were willing to serve through the wet seasons and the long cold winter nights. Secular knights who preferred a hot drink and a warm woman (or the other way around) were not eager to patrol dark paths in the forest or endure the freezing winds atop a lookout tower above lonely ramparts.

To assist in occupying the newly conquered territories, the Teutonic Knights settled secular knights on vacant lands in Culm, recruiting most of them from Poland; and in these early years they attracted burghers from Germany to found one new town a year, guaranteeing their rights in the Charter of Culm (1233). These immigrants were not numerous, though they would become so by the end of the thirteenth century, and were even more plentiful in the fourteenth. A large part of the fighting force, however, was composed of Prussian militiamen and nobles, the former serving as infantry, the latter as cavalry (often referred to – though slightly inaccurately – as ‘native knights’).

13

Whenever crusading forces were available, the Teutonic Knights, who were now experts on local topography and native customs, led the German and Polish knights, together with the allied Prussian cavalry and militiamen, down the Vistula River and along the coastline, capturing one fortress after another. There were distractions – in 1237 the Teutonic Knights incorporated a local military order, the Swordbrothers (see next chapter), and thereby took on additional responsibilities in Livonia that required diverting men and material to the north; then Pope Gregory IX excommunicated Emperor Friedrich II, precipitating a long and costly struggle that tore Germany apart; the Mongol onslaught of 1241 – 2 devastated Galicia-Volhynia, Hungary, and Poland, temporarily making it impossible for those powerful states to provide military assistance in the crusades; and in the 1240s Sventopełk of Pomerellia joined rebellious Prussians in an effort to drive the Teutonic Knights out of lands he wanted to make his own. This last conflict, the First Prussian Insurrection, was a close-run affair, but at last Sventopełk was forced to make peace, then forced again to surrender. Afterward the Prussian tribes negotiated a surrender that guaranteed them considerable autonomy in the conduct of their daily lives.

Meanwhile the Livonian branch of the order was also making headway in its offensives south from Riga. It seemed on the verge of a significant victory in 1250 when Mindaugas of Lithuania accepted Roman Christianity, thus removing the justification for attacking his lands. Although some critics of the Teutonic Order see the knights as nothing more than land-hungry robbers, in this instance they gave up an opportunity to seize territories in order to make one of Christendom’s greatest foes into a strong ally.

14

Shortly thereafter Prussian resistance began to collapse, too – in 1256 King Ottokar II of Bohemia, the most powerful single ruler in the Holy Roman Empire, led to Samland an army so powerful that the local natives realised resistance was futile. Shortly afterward, in 1257, the Samogitians asked for a two-year truce to consider their options. The crusaders granted this request, confident that self-interest would induce their foes to make a formal acceptance of the true faith. For a moment it appeared that Christendom had triumphed totally in the Baltic region.

The crusaders’ enthusiasm for peaceful conversions should give pause to those who cannot manage to disassociate the medieval mind from modern ideologies such as nationalism and racism, or who prefer to believe that the Germans were out to depopulate the entire region and resettle it. But it is unlikely that the Teutonic Knights will be judged by the most consistent of their statements and actions, for they, like most human organisations, exhibited over time a wide range of behaviours; if one always assumes the worst of them and the best from their foes, one can see them as evil, indeed; and that is the way that many historians, particularly those who judge the past as essentially part of the twentieth century, have written about these German warriors.

The crusading position began to come apart in 1259, when the Samogitians chose to fight for their pagan faith and traditional customs (which included raiding Christian settlements). They inflicted annihilating defeats upon Prussian and Livonian armies, forced Mindaugas to recant his conversion, and persuaded native peoples to the north and west to rise in revolt against their German masters. Soon Lithuanian armies were penetrating into Livonia, Prussia, Volhynia and Poland. Pagan victories seemed to confirm the rightness of the pagan religion. Holy War was now truly a contest of faiths, not merely a struggle between rulers as to who would rule.

This time the Teutonic Knights were more or less on their own. Neither German nor Polish crusaders came in great numbers, much less Bohemian monarchs and prelates. Moreover, the Holy Land became once again the centre of crusading energies, and the Teutonic Knights, like other military-religious orders, gave that region priority. The war in Prussia became a contest of border raids, sieges and surprises, and patrolling the wilderness to prevent the eastern Prussians and Lithuanians from coming through the depopulated Galindian forests and swamps to attack isolated settlements. Poles and Germans worked together to close the gap and eventually they were joined by Volhynians in carrying the war to the common enemy.