The 30 Day MBA (19 page)

Authors: Colin Barrow

It is also a continuous process that needs to be carried out periodically, for example when strategies are being reviewed.

Methods of segmentation

These are some of the ways by which markets can be segmented:

- Psychographic segmentation divides individual consumers into social groups such as âyuppies' (young, upwardly mobile professionals), âbumps' (borrowed-to-the-hilt, upwardly mobile, professional show-offs) and âjollies' (jet-setting oldies with lots of loot). These categories try to show how social behaviour influences buyer behaviour. Forrester Research, an internet research house, claims that when it comes to determining whether consumers will or will not go on the internet, how much they'll spend and what they'll buy, demographic factors such as age, race and gender don't matter anywhere near as much as the consumers' attitudes towards technology. Forrester uses this concept, together with its research, to produce Technographics® market segments as an aid to understanding people's behaviour as digital consumers. Forrester has used two categories: technology optimists and technology pessimists, and has used these alongside income and what it calls âprimary motivation' â career, family and entertainment â to divide up the whole market. Each segment is given a new name â âTechno-strivers', âDigital Hopefuls' and so forth â followed by a chapter explaining how to identify them, how to tell whether they are likely to be right for your product or service, and providing some pointers as to what marketing strategies might get favourable responses from each group.

- Benefit segmentation recognizes that different people can get different satisfaction from the same product or service. Lastminute.com claims two quite distinctive benefits for its users. First, it aims to offer people bargains that appeal because of price and value. Second, the company has recently been laying more emphasis on the benefit of immediacy. This idea is rather akin to the impulse-buy products placed at checkout tills, which you never thought of buying until you bumped into them on your way out. Whether 10 days on a beach in Goa or a trip to Istanbul are the type of things people âpop in their baskets' before turning off their computers, time will tell.

- Geographic segmentation arises when different locations have different needs. For example, an inner-city location may be a heavy user of motorcycle dispatch services, but a light user of gardening products. Internet companies have been slow to extend their reach beyond their own back yard, which is surprising considering the supposed global reach of the service. Microsoft exports only 20 per cent of its total sales beyond US borders, and fewer than 16 per cent of AOL's subscribers live outside the United States. However, the figure for AOL greatly overstates the company's true export performance. In reality, AOL does virtually no business with overseas subscribers, but instead serves them through affiliate relationships.

Few of the recent batch of internet IPOs have registered much overseas activity in their filing details. By way of contrast, the Japanese liquid crystal display industry exports more than 70 per cent of its entire output. - Industrial segmentation groups together commercial customers according to a combination of their geographic location, principal business activity, relative size, frequency of product use, buying policies and a range of other factors. Logical Holdings is an e-business solutions and service company that floated for over £1 ($1.6/â¬1.12) billion on the London Stock Exchange and TechMark index, making it one of the UK's biggest IT companies. It was formed from about 30 acquisitions of small (ish) businesses. The company was founded by Rikke Helms, formerly head of IBM's E-Commerce Solutions portfolio. Her company split the market into three segments: Small, Medium-Sized and Big, tailoring its services specifically for each.

- Multivariant segmentation is where more than one variable is used. This can give a more precise picture of a market than using just one factor.

Specifiers, users and customers

When analysing market segments it is important to keep in mind that there are at least three major categories of people who have a role to play in the buying decisions and whose needs have to be considered in any analysis of a market:

- The user, or end customer, will be the recipient of any final benefits associated with the product.

- The specifier will want to be sure that the end user's needs are met in terms of performance, delivery and any other important parameters. Their âcustomer' is both the end user and the budget holder of the cost centre concerned. There may even be conflict between the two (or more) âcustomer' groups. For example, in the case of, say, hotel toiletries, those responsible for marketing the rooms will want high-quality products to enhance their offer, while the hotel manager will have cost concerns close to the top of their concerns and the people responsible for actually putting the product in place will be interested only in any handling and packaging issues.

- The non-consuming buyer, who places the order, also has individual needs. Some of their needs are similar to those of a specifier, except that they will have price at or near the top of their needs. A particular category here is those buying gifts. Once again their needs and those of the recipient may be dissimilar. For example, those buying gifts are as concerned with packaging as with content. Watches, pens,

perfumes and fine wines are all gifts whose packaging is paramount at the point of purchase. Yet for the user they are often things to be immediately discarded.

The term âmarketing mix' has a pedigree going back to the late 1940s when marketing managers referred to mixing ingredients to create strategies. The concept was formalized by E Jerome McCarthy, a marketing professor at Michigan State University, in 1960. The mix of ingredients with which marketing strategy can be developed and implemented is price, product (or/and service), promotion and place. A fifth âP', people, is often added. Just as with cooking, taking the same or similar ingredients in different proportions can result in very different âproducts'. A change in the way these elements are put together can produce an offering tailored to meet the needs of a specific market segment.

The ingredients in the marketing mix represent only the elements that are largely, though not entirely, within a firm's control. Uncontrollable ingredients include the state of the economy, changes in legislation, new and powerful market entrants and rapid changes in technology. The effects of these external elements are covered in the chapter on strategy, though many of the concepts discussed there apply to marketing as well as to wider aspects of a firm's operations.

Product/service

When the term âmarketing mix' was first coined, the bulk of valuable trade was concerned with physical goods. Certainly services existed, but these were mostly supplied by professions such as law, accountancy, insurance and finance where the concept of marketing was in any event taboo; today, a product is generally accepted as the whole bundle of âsatisfactions', either tangible such as a physical product, or intangible such as warranties, guarantees or customer support that support that product. Generally the terms product and service will be used synonymously in this part of this chapter.

The bundle that makes up a successful product includes:

- design;

- specification and functionality;

- brand name/image;

- performance and reliability;

- quality;

- safety;

- packaging;

- presentation and appearance;

- after-sales service;

- availability;

- delivery;

- colour/flavour/odour/touch;

- payment terms.

The principal tools that marketing managers use to manage product issues are as follows.

Product/service life cycle

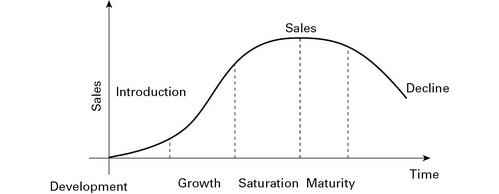

The idea that business products and services have a life cycle much as any being was first seen in management literature as far back as 1922, when researchers looking back at the growth of the US automobile industry observed a bell-shaped pattern for the sales of individual cars. Over the following four decades various practitioners and researchers, adding, substituting and renaming the stages in the life cycle to arrive at the five steps in

Figure 3.4

, carried out further work. The length of a product's lifetime can be weeks or months in the case of fads such as the hula-hoop or the Rubik's cube:

- Product development: This stage is typified by cash outlays only, and can last from decades in the case of medical products down to a few months or even weeks to launch a simple consumer product.

- Introduction: Here the product is brought to market, perhaps just to one initial segment, and it may comprise little more than a test marketing activity. Once again costs are high; advertising and selling costs have to be borne up front and sales revenues will be minimal.

- Growth: This stage sees the product sold across the whole range of a company's market segments, gaining market acceptance and becoming profitable.

- Maturity and saturation: Sales peak as the limit of customers' capacity to consume is reached and competitors or substitute products enter the market. Profits start to tail off as prices drop and advertising is stepped up to beat off competitors.

- Decline: Sales and profits fall away as competition becomes heavy and better and more competitive or technologically advanced products come into the market.

FIGURE 3.4

Â

The product life cycle

The usefulness of the product life cycle as a marketing tool is as an aid to deciding on the appropriate strategy to adopt. For example, at the introduction stage the goal for advertising and promotion may be to inform and educate, during the growth stage differences need to be stressed to keep competitors at bay, and during maturity customers need to be reminded that you are still around and it's time to buy again. During decline it's probable that advertising budgets could be cut and prices lowered. As all major costs associated with the product will have been covered at this stage, this should still be a profitable stage.

These, of course, are only examples of possible strategies rather than rules to be followed. For example, many products are successfully relaunched during the decline stage by changing an element of the marketing mix or by repositioning into a different marketplace. Cigarette manufacturers are responding to declining markets in the developed economies by targeting markets such as Africa and China, even setting up production there and buying up local brands to extend their range of products.

Unique positioning proposition

This used to be known as the unique selling proposition (USP) and still is in the sales field. For marketers the term is synonymous with the idea of a slogan or strap line that captures the value of the product in the mind of the user. It should position your product against competitors in a manner that is hard to emulate or dislodge. John Lewis, for example, has ânever knowingly undersold' as its powerful message to consumers that they can safely set price considerations to one side when they come to making their choice.

Another strategy is to set out to own the word and turn it into an adjective. Hoover with vacuum cleaners and FedEx with overnight delivery are examples of this approach.

Product range

Being a single-product business is generally considered too dangerous a position except for very small or start-up businesses. The two options to consider are:

- Depth of line: This is the situation when a company has many products within a particular category. Washing powders and breakfast cereals are classic examples of businesses that offer scores of products into the same marketplace. The benefit to the company is

that the same channels of distribution and buyers are being used. The weakness is that all these products are subject to similar threats and dangers. However âdeep' your beers and spirits range, for example, you will always face the threat of higher taxes or the opprobrium of those who think you are damaging people's health. - Breadth of line: This is where a company has a variety of products of different types such as Marlboro with cigarettes and fashion clothing, or 3M with its extensive variety of adhesives extending out to the Post-It Note.

Branding

Since the first edition of this book the world of brands has been transformed in ways not seen since the term itself, derived from the Old Norse brandr, meaning âto burn', entered the business lexicon. For a start, 2010 saw 13 brands from so called developing countries, including those from the BRIC countries â Brazil, Russia, India and China â enter the ranks of the world's top 100 most valuable brands. Brand refers to the custom of owners burning their mark (or brand) onto their goods, but burning of a different kind has swept over brands and their owners for reasons linked more or less to the recent global economic catastrophes. Whilst long-established companies such as Lehman Brothers, respected and feared in equal measure on Wall Street since before 1929, have been swept away, a host of new names have sprung up to take their place. Bank of China, first listed on the Hong Kong stock market in 2002, became the world's 24th most valuable brand in 2010, just behind HSBC, but well ahead of Citibank. That same year ICICI, India's largest bank by market capitalization, entered the listings as the 45th most valuable brand. So for the first time since its inception in 2006, the BrandZ Top 100, who provide an objective annual study of brand value and positioning, include brands from all four of the BRIC countries.