The 30 Day MBA (9 page)

Authors: Colin Barrow

The market price of an ordinary share divided by the earnings per share. The PE ratio expresses the market value placed on the expectation of future earnings, ie the number of years required to earn the price paid for the shares out of profits at the current rate.

The percentage return a shareholder gets on the âopportunity' or current value of their investment.

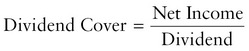

The number of times the profit exceeds the dividend; the higher the ratio, the more retained profit to finance future growth.

Other ratios

There are a very large number of other ratios that businesses use for measuring aspects of their performance such as:

- sales per £ invested in fixed assets â a measure of the use of those fixed assets;

- sales per employee â showing if your headcount is exceeding your sales growth;

- sales per manager, per support staff etc â showing the effectiveness of overhead spending.

Failure prediction

Unsurprisingly the financial crisis has inspired an interest in whether or not financial ratios can be used as indicators of business failure.

A study in 2012 by a research analyst from the FT Group, which was published in the

International Research Journal of Finance and Economics

, set out to identify appropriate analytical tools to predict factors that could lead to failure in good time for preventative measures to be taken. The study employed financial information for a group of 50 distressed and 50 non-distressed UK listed companies during the period 2000â2010.

The study looked at the three most popular failure prediction models and concluded that although the multiple discriminant analysis (MDA) model as used in Altman's Z-Score achieved a lower percentage of overall correct failure prediction (an average of 68.9 per cent all three years and 80 per cent for cumulative three years), it resulted in slightly higher overall percentage in the first year prior to failure.

The Altman Z-Score (

www.creditguru.com/CalcAltZ.shtml

) uses a combined set of five financial ratios derived from eight variables from a company's financial statements linked to some statistical techniques to predict a company's probability of failure. Entering the figures into the on-screen template at this website produces a score and an explanatory narrative giving a view on the business's financial strengths and weaknesses.

You can read up on the alternative ways to predict business failure in the article âPredicting Corporate Failure of UK's Listed Companies: Comparing Multiple Discriminant Analysis and Logistic Regression' (

http://connection.ebscohost.com/c/articles/78308524/predicting-corporate-failure-UKS-listed-companies-comparing-multiple-discriminant-analysis-logistic-regression

).

Some problems in using ratios

Finding the information to calculate business ratios is often not the major problem. Being sure of what the ratios are really telling you almost always is. The most common problems lie in the four following areas.

Which way is right?

There is natural feeling with financial ratios to think that high figures are good ones, and an upward trend represents the right direction. This theory is, to some extent, encouraged by the personal feeling of wealth that having a lot of cash engenders.

Unfortunately, there is no general rule on which way is right for financial ratios. In some cases a high figure is good, in others a low figure is best. Indeed, there are even circumstances in which ratios of the same value are not as good as each other. Look at the two working capital statements in

Table 1.12

.

TABLE 1.12

Â

Difficult comparisons

1 | 2 | |||

Current assets | $/£/⬠| $/£/⬠| $/£/⬠| $/£/⬠|

Stock | 10,000 | 22,990 | ||

Debtors | 13,000 | 100 | ||

Cash | 100 | 23,100 | 10 | 23,100 |

Less current liabilities | ||||

Overdraft | 5,000 | 90 | ||

Creditors | 1,690 | 6,690 | 6,600 | 6,690 |

Working capital | 16,410 | 16,410 | ||

Current ratio | 3.4 : 1 | 3.4 : 1 |

The amount of working capital in each example is the same, $/£/â¬16,410, as are the current assets and current liabilities, at $/£/â¬23,100 and $/£/â¬6,690 respectively. It follows that any ratio using these factors would also be the same. For example, the current ratios in these two examples are both identical, 3.4 : 1, but in the first case there is a reasonable chance that some cash will come in from debtors, certainly enough to meet the modest creditor position. In the second example there is no possibility of useful amounts of cash coming in from trading, with debtors at only $/£/â¬100, while creditors at the relatively substantial figure of $/£/â¬6,600 will pose a real threat to financial stability.

So in this case the current ratios are identical, but the situations being compared are not. In fact, as a general rule, a higher working capital ratio

is regarded as a move in the wrong direction. The more money a business has tied up in working capital, the more difficult it is to make a satisfactory return on capital employed, simply because the larger the denominator the lower the return on capital employed.

In some cases the right direction is more obvious. A high return on capital employed is usually better than a low one, but even this situation can be a danger signal, warning that higher risks are being taken. And not all high profit ratios are good: sometimes a higher profit margin can lead to reduced sales volume and so lead to a lower ROCE (return on capital employed).

In general, business performance as measured by ratios is best thought of as lying within a range, liquidity (current ratio), for example, staying between 1.2 : 1 and 1.8 : 1. A change in either direction represents a cause for concern.

Accounting for inflation

Financial ratios all use pounds as the basis for comparison: historical pounds at that. That would not be so bad if all these pounds were from the same date in the past, but that is not so. Comparing one year with one from three or four years ago may not be very meaningful unless we account for the change in value of the pound.

One way of overcoming this problem is to adjust for inflation, perhaps using an index, such as that for consumer prices. Such indices usually take 100 as their base at some time in the past, for example 2000. Then an index value for each subsequent year is produced showing the relative movement in the item being indexed.

Apples and pears

There are particular problems in trying to compare one business's ratios with another. A small new business can achieve quite startling sales growth ratios in the early months and years. Expanding from £10,000 sales in the first six months to £50,000 in the second would not be unusual. To expect a mature business to achieve the same growth would be unrealistic. For Tesco to grow from sales of £10 billion to £50 billion would imply wiping out every other supermarket chain. So some care must be taken to make sure that like is being compared with like, and allowances made for differing circumstances in the businesses being compared (or if the same business, the trading/economic environment of the years being compared).

It is also important to check that one business's idea of an account category, say current assets, is the same as the one you want to compare it with. The concepts and principles used to prepare accounts leave some scope for differences.

Seasonal factors

Many of the ratios that we have looked at make use of information in the balance sheet. Balance sheets are prepared at one moment in time, and

reflect the position at that moment; they may not represent the average situation. For example, seasonal factors can cause a business's sales to be particularly high once or twice a year, as with fashion retailers, for example. A balance sheet prepared just before one of these seasonal upturns might show very high stocks, bought in specially to meet this demand. Conversely, a look at the balance sheet just after the upturn might show very high cash and low stocks. If either of those stock figures were to be treated as an average it would give a false picture.

It will be very useful to look at other comparable businesses to see their ratios as a yardstick against which to compare your own business's performance. For publicly quoted and larger businesses whose accounts are audited this should not be too difficult. However, for smaller private companies the position is not quite so simple. In the first place, small companies need only file an abbreviated balance sheet. Even medium-sized businesses can omit turnover from the information filed on their financial performance. Only public companies listed on a stock market and larger companies have to provide full financial statements, though in many cases even the smallest companies choose to provide comfort to suppliers and potential employees.

Despite the limitation, it is still possible to glean some valuable information on financial performance using these sources:

- Companies House (

www.companieshouse.gov.uk

) is the official repository of all company information in the UK. Their WebCHeck service offers a free-of-charge searchable Company Names and Address Index, covering 2 million companies, searchable by either the company's name or its unique company registration number. You can use WebCHeck to purchase a company's latest accounts giving details of sales, profits, margins, directors, shareholders and bank borrowings at a cost of £1 per company. - Credit reports such as those provided by

www.ukdata.com

,

www.checksure.biz

and

www.business-inc.co.uk

cost around £8, are available online and provide basic business performance ratios. - FAME (Financial Analysis Made Easy) is a powerful database that contains information on 3.4 million companies in the UK and Ireland. Typically the following information is included: contact information including phone, e-mail and web addresses plus main and other trading addresses, activity details, 29 profit and loss account and 63 balance sheet items, cash flow and ratios, credit score and rating, security and price information (listed companies only), names of bankers, auditors, previous auditors and advisers, details

of holdings and subsidiaries (including foreign holdings and subsidiaries), names of current and previous directors with home addresses and shareholder indicator, heads of department, and shareholders. You can compare each company with detailed financials with its peer group based on its activity codes, and the software lets you search for companies that comply with your own criteria, combining as many conditions as you like. FAME is available in business libraries and on CD from the publishers, who also offer a free trial (

www.bvdinfo.com/Products/Company-Information/National/Fame

). - Key Note (

www.keynote.co.uk

) operates in 18 countries, providing business ratios and trends for 140 industry sectors and sufficient information to assess accurately the financial health of each industry sector. Using this service you can find out how profitable a business sector is and how successful the main companies operating in each sector are. Executive summaries are free, but expect to pay between £250/$392/â¬282 and £500/$784/â¬564 for most reports. - London Stock Exchange's website (

www.londonstockexchange.com

). - Proshare (

www.proshareclubs.co.uk

> Research Centre > Performance Tables) is an Investment Club website, which, once you have registered, which you can do for free, has a number of tools that crunch public company ratios for you. Select the companies you want to look at, then the ratios you are most interested in: EPS, P/E, ROI, Dividend Yield and so forth. Press the button and in a couple of seconds all is revealed. You can then rank the companies by performance in more or less any way you want. - Precision IR (

www.precisionir.com

) has direct links to several thousand public companies' âReport and Accounts' online, so you can save yourself the time and trouble of hunting down company websites.