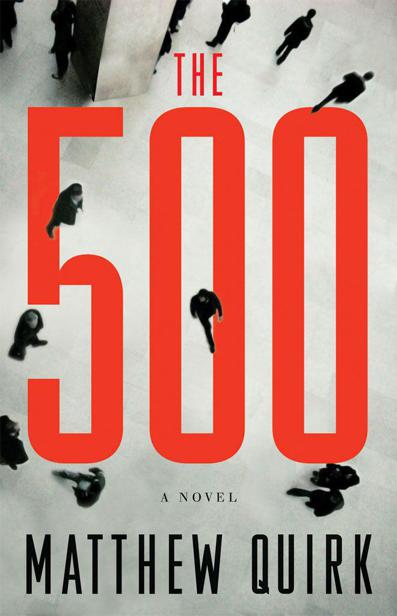

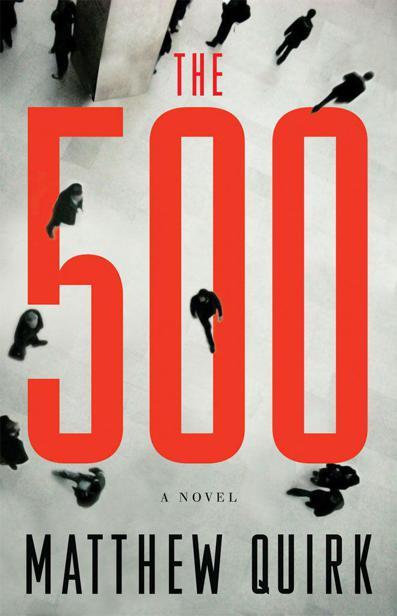

The 500: A Novel

Authors: Matthew Quirk

For Heather

MIROSLAV AND ALEKSANDAR

filled the front seats of the Range Rover across the street. They wore their customary diplomatic uniforms—dark Brionis tailored close—but the two Serbs looked angrier than usual. Aleksandar lifted his right hand high enough to flash me a glint of his Sig Sauer. A master of subtlety, that Alex. I wasn’t particularly worried about the two bruisers sitting up front, however. The worst thing they could do was kill me, and right now that looked like one of my better options.

The rear window rolled down and there was Rado, glaring. He preferred to make his threats with a dinner napkin. He lifted one up and dabbed gently at the corners of his mouth. They called him the King of Hearts because, well, he ate people’s hearts. The way I heard it was that he’d read an article in the

Economist

about some nineteen-year-old Liberian warlord with a taste for human flesh. Rado decided that sort of flagrant evil would give his criminal brand the edge it needed in a crowded global marketplace, so he picked up the habit.

I wasn’t even all that worried about him tucking into my heart. That’s usually fatal and, like I said, would greatly simplify my dilemma. The problem was that he knew about Annie. And my getting another loved one killed because of my mistakes was one of the things that made Rado’s fork look like the easy out.

I nodded to Rado and started up the street. It was a beautiful May morning in the nation’s capital, with a sky like blue porcelain. The blood that had soaked through my shirt was drying, stiff and scratchy. My left foot dragged on the asphalt. My knee had swollen to the size of a rugby ball. I tried to concentrate on the knee to keep my mind off the injury to my chest, because if I thought about that—not the pain so much as the sheer creepiness of it—I was sure I would pass out.

As I approached, the office looked as classy as ever: a three-story Federal mansion set back in the woods of Kalorama, among the embassies and chanceries. It was home to the Davies Group, Washington, DC’s most respected strategic consulting and government affairs firm, where I guess technically I may have still been employed. I fished my keys from my pocket and waved them in front of a gray pad beside the door lock. No go.

But Davies was expecting me. I looked up at the closed-circuit camera. The lock buzzed.

Inside the foyer, I greeted the head of security and noted the baby Glock he’d pulled from its holster and was holding tight near his thigh. Then I turned to Marcus, my boss, and nodded by way of hello. He stood on the other side of the metal detector, waved me through, then frisked me neck to ankle. He was checking for weapons, and for wires. Marcus had made a nice long career with those hands, killing.

“Strip,” Marcus said. I obliged, shirt and pants. Even Marcus winced when he saw the skin of my chest, puckering around the staples. He took a quick look inside my drawers, then seemed satisfied I wasn’t bugged. I suited back up.

“Envelope,” he said, and gestured to the manila one I was carrying.

“Not until we have a deal,” I said. The envelope was the only thing keeping me alive, so I was a little reluctant to let it go. “This will go wide if I disappear.”

Marcus nodded. That kind of insurance was standard industry practice. He’d taught me so himself. He led me upstairs to Davies’s office and stood guard by the door as I stepped inside.

There, standing by the windows, looking out over downtown DC, was the one thing I was worried about, the option that seemed much worse than getting carved up by Rado: it was Davies, who turned to me with a grandfather’s smile.

“It’s good to see you, Mike. I’m glad you decided to come back to us.”

He wanted a deal. He wanted to feel like he owned me again. And that’s what I was afraid of more than anything else, that I would say yes.

“I don’t know how things got this bad,” he said. “Your father…I’m sorry.”

Dead, as of last night. Marcus’s handiwork.

“I want you to know we didn’t have anything to do with that.”

I said nothing.

“You might want to ask your Serbian friends about it. We can protect you, Mike; we can protect the people you love.” He told me to sit down at the far end of the conference table, and he moved a little closer. “Just say it and all this is over. Come back to us, Mike. It only takes one word: yes.”

And that was the weird thing about all his games, all the torture. At the end of the day he really thought he was doing me a favor. He wanted me back, thought of me as a son, a younger version of himself. He had to corrupt me, to own me, or else everything he believed, his whole sordid world, was a lie.

My dad chose to die instead of playing ball with Davies. Die proud rather than live corrupted. He got out. It was so neat and clean. But I didn’t have that luxury. My death would be only the beginning of the pain. I had no good options. That’s why I was here, about to shake hands with the devil.

I placed the envelope on the table. Inside it was the only thing Henry was afraid of: evidence of a mostly forgotten murder. His only mistake. The one bit of carelessness in Davies’s long career. It was a piece of himself he’d lost fifty years before, and he wanted it back.

“This is the only real trust, Mike. When two people know each other’s secrets. When they have each other cornered. Mutually assured destruction. Anything else is bullshit sentimentality. I’m proud of you. It’s the same play I made when I was starting out.”

Henry always told me that every man has his price. He’d found mine. If I said yes, I’d have my life back—the house, the money, the friends, the respectable facade I’d always wanted. If I said no, it was all over, for me, for Annie.

“Name your price, Mike. You can have it. Anyone who’s anyone has made a deal like this on the way up. It’s how the game is played. What do you say?”

It was an old bargain. Swap your soul for all the kingdoms of the world and their glory. There would be haggling over details, of course. I wasn’t going to sell myself on the cheap, but that was quickly squared away.

“I will give you this evidence,” I said, tapping my finger on the envelope, “and guarantee that you will never have to worry about it again. In exchange, Rado goes away. The police leave me alone. I get my life back. And I become a full partner.”

“And from now on, you’re mine,” Henry said. “A full partner in the wet work too. When we find Rado, you’ll slit his throat.”

I nodded.

“Then we’re agreed,” Henry said. The devil held his hand out.

I shook it, and handed over my soul with the envelope.

But that was bullshit, another gamble. Die in infamy, honor intact, or live in glory, corrupted. I chose neither. There was nothing in the envelope. I was trying to barter empty-handed with the devil, so I really had only one choice: to beat him at his own game.

I WAS LATE.

I checked myself out in one of the giant gilt mirrors they had hanging everywhere. There were dark circles under my eyes from lack of sleep and a fresh patch of carpet burn on my forehead. Otherwise I looked like every other upwardly mobile grade-grubber streaming through Langdell Hall.

The seminar was called Politics and Strategy. I ducked inside. It was application only—sixteen spots—and had the reputation of being a launching pad for future leaders in finance, diplomacy, military, and government. Every year Harvard tapped a few mid- to late-career heavies from DC and New York and brought them up to lead the seminar. The class was essentially a chance for the wannabe big-deal professional students—and there was no shortage of them around campus—to show off their “big think” skills, hoping establishment dons would tap them and start them off on glittering careers. I looked around the table: hotshots from the law school, econ, philosophy, even a couple MD/PhDs. Ego poured through the room like central air.

It was my third year at the law school—I was doing a joint law and politics degree—and I had no idea how I’d managed to finagle my way into HLS or the seminar. That’d been pretty typical of the past ten years of my life, though, so I shrugged it off. Maybe it was all just a long series of clerical errors. My usual attitude was the fewer questions asked, the better.

Jacket, button-down, khakis: I mostly managed to look the part, if a little worn and frayed. We were in the thick of the conversation. The subject was World War I. And Professor Davies stared at us expectantly, sweating the answer out of us like an inquisitor.

“So,” Davies said. “Gavrilo Princip steps forward and pistol-whips a bystander with his little Browning 1910. He shoots the archduke in the jugular and then shoots his wife through the stomach as she shields the archduke with her body. He just so happens to trigger the Great War in the process. The question is: Why?”

He glowered around the table. “Don’t regurgitate what you read. Think.”

I watched the others squirm. Davies definitely qualified as a heavy. The other students in class had studied his career with jealous obsession. I knew less, but enough. He was an old Washington hand. Going back forty years, he knew everyone who mattered, the two layers of people below those who mattered, and, most important, where all the bodies were buried. He’d worked for Lyndon Johnson, jumped ship to Nixon, then put out his own shingle as a fixer. He now ran a high-end strategic consulting firm called the Davies Group, which always made me think of the Kinks (that should tell you a bit about how fit I am for cutthroat DC career climbing). Davies had influence and could trade on that for anything he wanted, including, as one of the guys in class pointed out, a mansion in McLean, a place in Tuscany, and a ten-thousand-acre ranch on the central California coast. He’d been guest-teaching the seminar for a few weeks now. My classmates were practically vibrating with anxiety; I’d never seen them so eager to impress. That led me to believe that in the various orbits of official Washington, Davies had pull like the sun.

Davies’s usual teaching method was to sit placidly and put a good face on his boredom, like he was listening to a bunch of second-graders spout dinosaur trivia. He wasn’t an especially large man, maybe five ten, five eleven, but he sort of…loomed. His pull, it was almost like you could see it spread out through a room. People stopped talking, all eyes turned to him, and soon enough he had everyone lined up around him like filings around a magnet.

But his voice: that was the odd thing. You’d expect it to boom out, but he always spoke softly. There was a scar on his neck, right between where his jawline met his ear. It was the source of some speculation, whether an old injury had something to do with his quiet tone, but no one knew what had happened. It didn’t matter much, since most rooms went silent when he opened his mouth. In class, though, his students were desperate to be heard, to be noticed by the master. Everyone had his answers to Davies’s questions marshaled. There’s an art to seminar: when to let others blabber, when to cut in. It’s like boxing or…I guess fencing or squash or one of those other Ivy League pastimes.