The 9/11 Wars (87 page)

Authors: Jason Burke

Tags: #Political Freedom & Security, #21st Century, #General, #United States, #Political Science, #Terrorism, #History

4. The ruins of the World Trade Center. Nearly 3,000 died in the September 11 attacks on New York and Washington. Rooted in a strategy of ‘propaganda by deed’, viewed by hundreds of millions of people, their significance would be defined as much by the reaction to the strategy as by the number of people it killed or the economic damage it caused.

5. The fighting at Tora Bora in eastern Afghanistan in December 2001 was less the last stand portrayed by Western media than a chaotic fighting retreat by international militants. With its lack of clear frontlines, blurring of civilians and soldiers and the conflicting agendas even of allies, it presaged much of the combat in the 9/11 Wars.

6. The aftermath of the Bali bombing. Through 2002, veterans of the al-Qaeda training camps in Afghanistan and existing militant networks around the Islamic world launched attacks from Morocco to Indonesia. Some strikes could be directly attributed to bin Laden or associates; others were the work of independent groups. The blasts in Bali killed more than 200 and were the bloodiest.

7. Anti-war march, London. The invasion of Iraq – at least without a specific United Nations resolution – was opposed by the vast majority of Europeans and many Americans too. It took the 9/11 Wars into new territory, bringing an extension and an intensification of the violence as well as sparking a wave of anger in the Muslim world not seen since the 1970s.

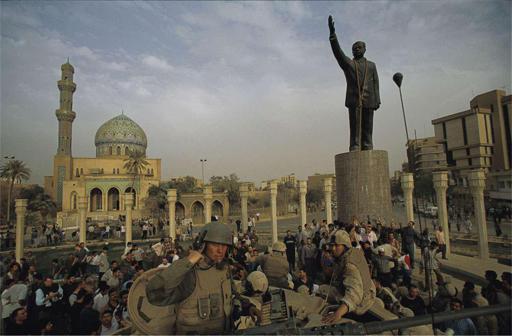

8. The Iraq War. The invasion campaign was supposed to last 100 days. In the end Saddam Hussein’s detested and brutal regime collapsed much more quickly. But errors made in the spring and summer of 2003 – most rooted in a grave lack of preparedness and huge overconfidence – soon saw the situation in the country deteriorating very quickly.

9. The Iraq War. Heavy-handed coalition tactics, indiscriminate raids such as this one in search of an elusive enemy and deep ignorance of Iraqi society all helped fuel an insurgency. Within months, it was the fast-adapting networks of irregular Iraqi fighters that had seized the initiative from the slow-moving American army.

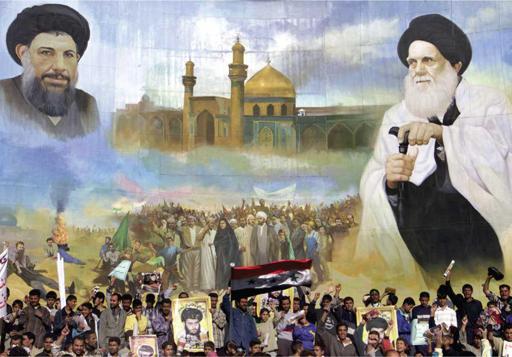

10. After the invasion, the Iraqi Shia population experienced a potent cultural revival. For young, unemployed, uneducated urban men, the attraction of populist revolutionary Islamism was strong. Here, followers of the young cleric Moqtada al-Sadr carry his picture and chant under a banner of his father-inlaw and father, both murdered by Saddam Hussein’s regime. Tens of thousands joined his al-Mahdi Army.

11. Murals on a Tehran street. The abuse of Iraqi prisoners by US soldiers at Abu Ghraib prison in western Baghdad revealed in March 2004 was cited by militants everywhere as a key in convincing them to participate in the ‘jihad’. Though there was much abuse elsewhere, the image of a hooded prisoner threatened with a mock electrocution became an icon of the 9/11 Wars.

12. Jordanian-born Abu Musab al-Zarqawi was a former petty criminal and veteran militant who only reluctantly joined al-Qaeda in late 2004. A believer in seizing territory as a base for ‘jihad’, his taste for extreme and indiscriminate violence as well as his lack of respect for local Iraqi tribal leaders eventually alienated local and international supporters.

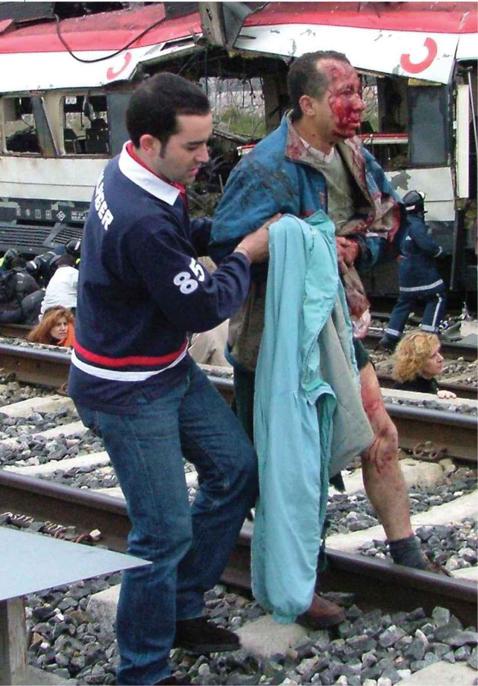

13. The aftermath of the Madrid train bombing. In March 2004 a series of bombs exploded on commuter trains in Madrid, Spain. Planted by a group of recent immigrants with no links to al-Qaeda who had been living in Spain for some time, it signalled the arrival of the 9/11 Wars in Europe and was a step towards ‘home-grown’ terrorism.