The Adventures and Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes (60 page)

Read The Adventures and Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes Online

Authors: Arthur Conan Doyle

âI trust you had no more of those nervous attacks.'

Sherlock Holmes laughed heartily. âWe will come to that in its turn,' said he. âI will lay an account of the case before you in its due order, showing you the various points which guided me in my decision. Pray interrupt me if there is any inference which is not perfectly clear to you.

âIt is of the highest importance in the art of detection to be able to recognize out of a number of facts which are incidental and which vital. Otherwise your energy and attention must be dissipated instead of being concentrated. Now, in this case there was not the slightest doubt in my mind from the first that the key of the whole matter must be looked for in the scrap of paper in the dead man's hand.

âBefore going into this I would draw your attention to the fact that if Alec Cunningham's narrative were correct, and if the assailant after shooting William Kirwan had

instantly

fled, then it obviously could not be he who tore the paper from the dead man's hand. But if it was not he, it must have been Alec Cunningham himself, for by the time the old man had descended several servants were upon the scene. The point is a simple one, but the Inspector had overlooked it because he had started with the supposition that these county magnates had had nothing to do with the matter. Now, I make a point of never having any prejudices and of following docilely wherever fact may lead me, and so in the very first stage of the investigation I found myself looking a little askance at the part which had been played by Mr Alec Cunningham.

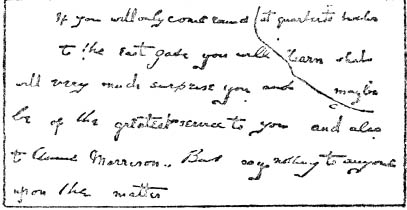

âAnd now I made a very careful examination of the corner of paper which the Inspector had submitted to us. It was at once clear to me that it formed part of a very remarkable document. Here it is. Do you not now observe something very suggestive about it?'

âIt has a very irregular look,' said the Colonel.

âMy dear sir,' cried Holmes, âthere cannot be the least doubt in the world that it has been written by two persons doing alternate words. When I draw your attention to the strong t's of “at” and “to” and ask you to compare them with the weak ones of “quarter” and “twelve,” you will instantly recognize the fact. A very brief analysis of those four

words would enable you to say with the utmost confidence that the “learn” and the “may be” are written in the stronger hand, and the “what” in the weaker.'

âBy Jove, it's as clear as day!' cried the Colonel. âWhy on earth should two men write a letter in such a fashion?'

âObviously the business was a bad one, and one of the men who distrusted the other was determined that, whatever was done, each should have an equal hand in it. Now, of the two men it is clear that the one who wrote the “at” and “to” was the ringleader.'

âHow do you get at that?'

âWe might deduce it from the mere character of the one hand as compared with the other. But we have more assured reasons than that for supposing it. If you examine this scrap with attention you will come to the conclusion that the man with the stronger hand wrote all his words first, leaving blanks for the other to fill up. These blanks were not always sufficient, and you can see that the second man had a squeeze to fit his “quarter” in between the “at” and the “to”, showing that the latter were already written. The man who wrote all his words first is undoubtedly the man who planned this affair.'

âExcellent!' cried Mr Acton.

âBut very superficial,' said Holmes. âWe come now, however, to a point which is of importance. You may not be aware that the deduction of a man's age from his writing

8

is one which has been brought to considerable accuracy by experts. In normal cases one can place a man in his true decade with tolerable confidence. I say normal cases, because ill-health and physical weakness reproduce the signs of old age, even when the invalid is a youth. In this case, looking at the bold, strong hand of the one, and the rather broken-backed appearance of the other, which still retains its legibility, although the

t

's have begun to lose their crossings, we can say that the one was a young man, and the other was advanced in years without being positively decrepit.'

âExcellent!' cried Mr Acton again.

âThere is a further point, however, which is subtler and of greater interest. There is something in common between these hands. They belong to men who are blood-relatives. It may be most obvious to you in the Greek

e

's, but to me there are many smaller points which

indicate the same thing. I have no doubt at all that a family mannerism can be traced in these two specimens of writing. I am only, of course, giving you the leading results now of my examination of the paper. There were twenty-three other deductions

9

which would be of more interest to experts than to you. They all tended to deepen the impression upon my mind that the Cunninghams, father and son, had written this letter.

âHaving got so far, my next step was, of course, to examine into the details of the crime and to see how far they would help us. I went up to the house with the Inspector, and saw all that was to be seen. The wound upon the dead man was, as I was able to determine with absolute confidence, caused by a shot from a revolver fired at a distance of something over four yards. There was no powder-blackening on the clothes. Evidently, therefore, Alec Cunningham had lied when he said that the two men were struggling when the shot was fired. Again, both father and son agreed as to the place where the man escaped into the road. At that point, however, as it happens, there is a broadish ditch, moist at the bottom. As there were no indications of boot-marks about this ditch, I was absolutely sure not only that the Cunninghams had again lied, but that there had never been any unknown man upon the scene at all.

âAnd now I had to consider the motive of this singular crime. To get at this I endeavoured first of all to solve the reason of the original burglary at Mr Acton's. I understood from something which the Colonel told us that a lawsuit had been going on between you, Mr Acton, and the Cunninghams. Of course, it instantly occurred to me that they had broken into your library with the intention of getting at some document which might be of importance in the case.'

âPrecisely so,' said Mr Acton; âthere can be no possible doubt as to their intentions. I have the clearest claim upon half their present estate, and if they could have found a single paper â which, fortunately, was in the strong-box of my solicitors â they would undoubtedly have crippled our case.'

âThere you are!' said Holmes, smiling. âIt was a dangerous, reckless attempt, in which I seem to trace the influence of young Alec. Having found nothing, they tried to divert suspicion by making it appear to

be an ordinary burglary, to which end they carried off whatever they could lay their hands upon. That is all clear enough, but there was much that was still obscure. What I wanted above all was to get the missing part of that note. I was certain that Alec had torn it out of the dead man's hand, and almost certain that he must have thrust it into the pocket of his dressing-gown. Where else could he have put it? The only question was whether it was still there. It was worth an effort to find out, and for that object we all went up to the house.

âThe Cunninghams joined us, as you doubtless remember, outside the kitchen door. It was, of course, of the very first importance that they should not be reminded of the existence of this paper, otherwise they would naturally destroy it without delay. The Inspector was about to tell them the importance which was attached to it when, by the luckiest chance in the world, I tumbled down in a sort of fit and so changed the conversation.'

âGood heavens!' cried the Colonel, laughing. âDo you mean to say all our sympathy was wasted and your fit an imposture?'

âSpeaking professionally, it was admirably done,' cried I, looking in amazement at this man who was forever confounding me with some new phase of his astuteness.

âIt is an art which is often useful,' said he. âWhen I recovered I managed by a device, which had, perhaps, some little merit of ingenuity, to get old Cunningham to write the word “twelve” so that I might compare it with the “twelve” upon the paper.'

âOh, what an ass I have been!' I exclaimed.

âI could see that you were commiserating with me over my weakness,' said Holmes, laughing. âI was sorry to cause you the sympathetic pain which I know that you felt. We then went upstairs together, and having entered the room and seen the dressing-gown hanging up behind the door, I contrived by upsetting a table to engage their attention for the moment and slipped back to examine the pockets. I had hardly got the paper, however, which was as I had expected, in one of them, when the two Cunninghams were on me, and would, I verily believe, have murdered me then and there but for your prompt and friendly aid. As it is, I feel that young man's grip on my throat now, and the father has twisted my wrist round in the effort to get the

paper out of my hand. They saw that I must know all about it, you see, and the sudden change from absolute security to complete despair made them perfectly desperate.

âI had a little talk with old Cunningham afterwards as to the motive of the crime. He was tractable enough, though his son was a perfect demon, ready to blow out his own or anybody else's brains if he could have got to his revolver. When Cunningham saw that the case against him was so strong he lost all heart, and made a clean breast of everything. It seems that William had secretly followed his two masters on the night when they made their raid upon Mr Acton's, and, having thus got them into his power, proceeded under threats of exposure to levy blackmail upon them. Mister Alec, however, was a dangerous man to play games of that sort with. It was a stroke of positive genius on his part to see in the burglary scare, which was convulsing the country-side, an opportunity of plausibly getting rid of the man whom he feared. William was decoyed up and shot and, had they only got the whole of the note, and paid a little more attention to detail in their accessories, it is very possible that suspicion might never have been aroused.'

âAnd the note?' I asked.

Sherlock Holmes placed the subjoined paper before us.

âIt is very much the sort of thing that I expected,' said he. âOf course, we do not yet know what the relations may have been between Alec Cunningham, William Kirwan, and Annie Morrison. The result

shows that the trap was skilfully baited. I am sure that you cannot fail to be delighted with the traces of heredity shown in the

p

's and in the tails of the

g

's. The absence of the

i

-dots in the old man's writing is also most characteristic. Watson, I think our quiet rest in the country has been a distinct success, and I shall certainly return, much invigorated, to Baker Street tomorrow.'

One summer night, a few months after my marriage, I was seated by my own hearth smoking a last pipe and nodding over a novel, for my day's work had been an exhausting one. My wife had already gone upstairs, and the sound of the locking of the door some time before told me that the servants had also retired. I had risen from my seat and was knocking out the ashes of my pipe, when I suddenly heard the clang of the bell.

I looked at the clock. It was a quarter to twelve. This could not be a visitor at so late an hour. A patient, evidently, and possibly an all-night sitting. With a wry face I went out into the hall and opened the door. To my astonishment, it was Sherlock Holmes who stood upon my step.

âAh, Watson,' said he, âI hoped that I might not be too late to catch you.'

âMy dear fellow, pray come in.'

âYou look surprised, and no wonder! Relieved, too, I fancy! Hum! you still smoke the Arcadia mixture of your bachelor days, then! There's no mistaking that fluffy ash upon your coat. It's easy to tell that you've been accustomed to wear a uniform, Watson; you'll never pass as a pure-bred civilian as long as you keep that habit of carrying your handkerchief in your sleeve. Could you put me up tonight?'

âWith pleasure.'

âYou told me that you had bachelor quarters for one, and I see that you have no gentleman visitor at present. Your hat-stand proclaims as much.'

âI shall be delighted if you will stay.'

âThank you. I'll find a vacant peg, then. Sorry to see that you've had the British workman in the house. He's a token of evil. Not the drains, I hope?'

âNo, the gas.'

âAh! He has left two nail marks from his boot upon your linoleum just where the light strikes it. No, thank you, I had some supper at Waterloo, but I'll smoke a pipe with you with pleasure.'

I handed him my pouch, and he seated himself opposite to me, and smoked for some time in silence. I was well aware that nothing but business of importance could have brought him to me at such an hour, so I waited patiently until he should come round to it.