The Air-Raid Warden Was a Spy: And Other Tales From Home-Front America in World War II (18 page)

Read The Air-Raid Warden Was a Spy: And Other Tales From Home-Front America in World War II Online

Authors: William B. Breuer

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #aVe4EvA

Yet another new resident of Lake Geneva was Seward Bishop Collins, a rich New Yorker, who settled in a large estate and began collecting tens of thousands of dollars worth of shortwave radio equipment in his spacious four garages. Collins continued to maintain a bookstore at 231 West 58th Street, New York City, which served as a regular meeting place for Nazi agents.

In August 1941, Douglas M. Stewart and George Eggleston gave birth at Lake Geneva to a newspaper called The Herald. Later investigation by federal authorities would disclose that the propaganda sheet was being financed by Charles S. Payson, a New York City multimillionaire.

Psychological Saboteurs at Work

87

arm that number of young American men to overthrow the government in Washington and to “bring Franklin Roosevelt to trial.”

Senator Robert R. Reynolds of North Carolina, chairman of the Senate Military Affairs Committee, wrote a letter to Smith: “Let me congratulate you with my full heart upon your [magazine]. It hits the bull’s eye with every paragraph; it should have its appeal; it speaks the truth.”

Naturally, Smith used this glowing letter from one of the most powerful men in Congress to promote subscriptions to The Cross and the Flag.

When questioned by Washington journalists about his endorsement of Gerald L. K. Smith’s propaganda sheet, Senator Reynolds declared: “I have no apologies to offer for endorsing the program of any individual or group standing for the same things I have stood for many years.”

Indeed Reynolds had made no effort to conceal his pro-Nazi views. Three years earlier, on February 5, 1939, the Voelkischer Beobachter, Adolf Hitler’s official newspaper, had carried an article with the by-line “Senator Robert R. Reynolds of North Carolina.”

Reynolds’s article was headlined: “Advice to Roosevelt; Stick to Your Knitting.” The senator was quoted as saying: “I can see no reason why the youth of [America] should be uniformed to save the so-called democracies of Europe— imperialistic Great Britain and Communist France.”

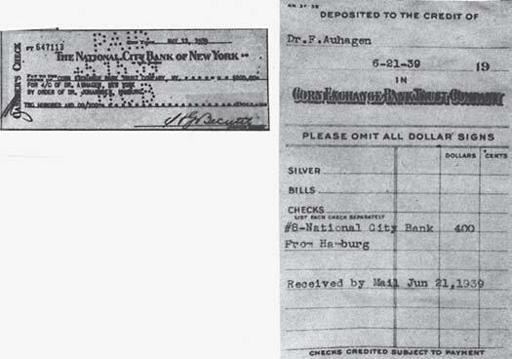

Undoubtedly, the King of Psychological Saboteurs in America was George Sylvester Viereck, editor of Today’s Challenge, the propaganda newspaper put out by Friedrich Auhagen’s American Fellowship Forum. Viereck was born in Munich and came to the United States in the early 1900s. Glib, shrewd, and energetic, a gifted and crafty writer of propaganda pieces, he may have been history’s highest-paid psychological saboteur.

Prior to America’s entry into the war, Viereck admitted to a congressional committee that he had been pocketing some $3,250 (equivalent to $40,000 in 2002) per month from several different German organizations in the United States. Nearly all of the money had been sent by Berlin.

Viereck’s “front” was a correspondent for the Münchner Nauests Nachrichten, whose editor was Giselher Wirsing, a confidant of Hitler’s Minister of Enlightment (propaganda), Josef Goebbels.

Viereck, who maintained plush apartments in New York City and in Washington, had insinuated his way into the good graces of two like-minded members of Congress, Senator Ernest Lundeen of Minnesota and Representative Hamilton Fish of New York.

Using Fish’s room 1424 in the House Office Building for bulk mailing, Viereck launched an enormous propaganda operation. With the congressman’s frank (free mailing privileges), Viereck flooded the nation with reprints of anti-Roosevelt editorials, transcripts of radio broadcasts, newspaper and magazine clippings, and anything else that might serve Adolf Hitler’s cause.

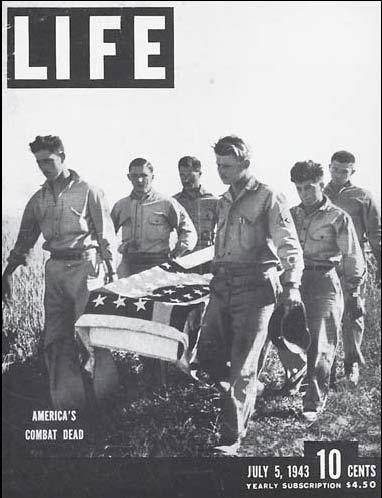

This clever imitation of a highly popular American magazine was created by propaganda artists in Berlin and gained limited distribution on home-front America. The phony picture shows Germans in GI uniforms. This issue featured race riots. (National Archives)

After Pearl Harbor, the Nazi psychological sabotage campaign hardly missed a beat. Only the strategy was changed. The keep-America-out-of-the-war theme was scuttled. In its place was an all-out effort to undermine the people’s confidence in the Washington leadership, stir up prejudices against America’s allies, foment racial strife and violence, and create artificial antagonisms between business and labor.

Finally, President Roosevelt ordered a crackdown on the raft of psychological saboteurs, who, in peacetime and through the first months of Uncle Sam’s going to war, enjoyed impunity.

Even the cagey George Viereck’s luck ran out. On March 14, 1942, he was sentenced to a term of two to four years in federal prison. A jury had found that operating a Nazi propaganda mill in the U.S. Capitol was not a legitimate pursuit for a “journalist.”

Frail, nervous introverted George Hill, secretary to Congressmen Hamilton Fish, had been duped into doing the actual propaganda mailings for Viereck. He was given a term of two to four years. Fish, who denied any knowledge of the machinations that had taken place under his nose, was never charged.

Among others who heard prison doors slam shut behind them was Ralph Townsend, the suspected spy for Japan and editor of The Herald and Scribner’s

Hollywood Superstars Sign Up to Fight

89

Commentator in Lake Geneva, who was sentenced to eight months to two years for failing to register as an enemy agent.

Even after the conviction of these psychological saboteurs, many propaganda publications continued in business. Then, on July 23, 1942, a federal grand jury in Washington indicted twenty-seven men and one woman on charges of conspiracy to provoke mutiny and disloyalty among members of the armed forces. Listed were thirty publications as vehicles through which the defendants had tried to sabotage morale.

Nearly all of those indicted were found guilty and received varied sentences. Their propaganda sheets went out of business.

14

Hollywood Superstars Sign Up to Fight

W

ITHOUT FANFARE OR MEDIA HYPE,

Hollywood superstar Clark Gable quietly slipped into an Army recruiting station in Los Angeles and was sworn in as a private. It was August 12, 1942.

Newspapers got word, and they played up the story. A $7,500-a-week (equivalent of $100,000 in the year 2002) movie idol giving up that salary and going into the service as a $21-a-month private made big headlines.

Hollywood actor Jimmy Stewart is decorated for flying twenty-five combat missions over Europe as a bomber pilot. (U.S. Air Corps)

Soon the overage-in-grade private was enrolled at the Officer Candidate School at Miami Beach, Florida. Twelve weeks later, he donned the bars of a second lieutenant in the Air Corps.

In the months ahead, Gable was in Flying Fortress bombers on missions over Germany to film footage for training gunners. Reichsmarschall Hermann Goering, the rotund leader of the Luftwaffe, reportedly put a large bounty on Gable’s head, a reward to any German pilot who would shoot him down.

Also serving in combat with the Air Corps in Europe was another Hollywood superstar, lanky, drawling Jimmy Stewart, who had received an Oscar in 1940.

He had been deferred from the draft because he was underweight (one hundred and forty pounds on a six-foot-two-inch frame). However, Stewart gorged himself with food, put on ten pounds, and barely qualified for acceptance in the Air Corps.

In Europe, Major Stewart would fly twenty-five combat missions as a pilot of a four-engine bomber named Four Yanks and a Jerk.

15

War Hero Meets Joe Kennedy

A

FTER HIS RETURN FROM THE PACIFIC

in the spring of 1942, newly promoted Lieutenant Commander John Bulkeley, called America’s Number-One Hero by the media, had been assigned by the Navy to recruit skippers for PT boats that would be heading for the war zone in greatly increased numbers. In his search, Bulkeley concentrated on Ivy League universities, because a basic requirement for a candidate was that he had had experience in handling small boats. Because most Ivy Leaguers were from wealthy families, they had owned their own craft and had grown up around yacht clubs.

In mid-September 1942, Bulkeley had a brief respite from his cross-county jaunts when he received a telegram signed Joseph P. Kennedy Sr. at his wife’s apartment in New York City. Bulkeley and Alice were invited to be Kennedy’s guest for lunch the next day at the posh Plaza Hotel.

Joe Kennedy, Bulkeley knew, had been the son of a Boston saloonkeeper and Democratic ward heeler, and he became a self-made multimillionaire in an era where that financial breed was rare.

Although away from home much of the time tending to his extensive business interests around the country and abroad, Kennedy Senior took an intensive interest in his five daughters and four sons, setting up a $1 million trust fund for each when he or she reached the age of twenty-one. The father encouraged—even demanded—that his offspring excel, planned their educations, and closely monitored their romances, of which there would be no shortage among the sons.

War Hero Meets Joe Kennedy

91

Kennedy Senior’s oldest son, Joseph P. Jr., and next oldest, John F., were both handsome, poised, energetic, and articulate. They had been ticketed by their father to become world-famous political figures—even president of the United States at an early age, one or the other.

Daddy Joe may have been a little disappointed over John F.’s political potential, for the personable youth had failed to survive even the primaries in an effort to become freshman class president at Harvard.

Now, at the appointed hour—1:00

P

.

M

.—Bulkeley and his wife arrived at Joe Kennedy’s large and ornate suite in the Plaza Hotel. To Bulkeley, Kennedy immediately conveyed the impression of a sharp businessman bent on completing a deal. But the host did open a conversation by asking about Bulkeley’s trip to the White House a few weeks earlier when President Roosevelt presented the Congressional Medal of Honor to the war hero.

The very mention of Franklin Roosevelt seemed to make Kennedy angry. Because of Kennedy’s outspoken remarks that seemed to many to have had a pro-German cast to them while ambassador to England, Roosevelt had fired his old pal. So when lunch was being served, the patriarch of the Kennedy clan launched a long diatribe against Roosevelt.

Then the host got down to the business at hand. He said his son Jack (John F.) was a midshipman (one in training for an officer’s commission) at Northwestern University in suburban Chicago. Jack had the potential to be president of the United States, the father declared. So he wanted Jack to get into the “glamorous” PT boat service for the publicity, to get the veterans’ vote after the war.