The Air-Raid Warden Was a Spy: And Other Tales From Home-Front America in World War II (26 page)

Read The Air-Raid Warden Was a Spy: And Other Tales From Home-Front America in World War II Online

Authors: William B. Breuer

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #aVe4EvA

In September 1943, Lehmitz, whose spying had no doubt resulted in the deaths of countless merchant seamen, was tried for wartime espionage in federal court in Brooklyn. He was sentenced to a term of thirty years in prison.

21

America’s Least-Known Boomtown

I

N MID-1943,

folks in eastern Tennessee knew that something big was taking place in and around what had been the sleepy little town of Oak Ridge. But as far as the rest of the United States was concerned, Oak Ridge didn’t exist. Only a tiny group of federal officials and scientists were aware that Oak Ridge would become one of the most important communities that history has known.

America’s Least-Known Boomtown

129

Back in June 1942, at the urging of a group of America’s foremost scientists, President Roosevelt secretly gave the green light to develop a revolutionary device of gargantuan destructive power that would be known as an atomic bomb. The colossal experiment was code-named Manhattan Project. (The Germans, too, were working to develop an atomic bomb.)

Soon a band of federal officials quietly descended upon the Oak Ridge region and purchased fifty-two thousand acres of land. On this site, a huge laboratory would be built in a crash program.

Oak Ridge had been selected for the atomic laboratories because of the abundance of water and electric power in that region. But mainly, its strategic location in hills and valleys, in a sparsely populated region, would help mask the true nature of the project. About a thousand families had to be moved to clear the area. They were told that a factory to build goods for the home front was going to be constructed.

Soon Oak Ridge became a boomtown as hundreds of engineers and construction workers moved in. Everything was supersecret. By 1943, Oak Ridge had about fifty thousand residents, becoming the fifth largest town in Tennessee.

The Manhattan Project had AAA priority—the highest. Brigadier General Leslie R. Groves, a forty-six-year-old West Pointer who had recently completed building the huge Pentagon outside Washington, took command of the operation. What followed was an only-in-America miracle. The nation was embarking on the most prodigious scientific-industrial-military enterprise ever conceived.

Groves’ task boggled the mind. Without known tools, blueprints, or materials, he would try to transform an invisible compound of equations, theory, and scientific faith into a practical military weapon.

The hulking Groves, who had longed for a combat command in Europe after the Pentagon job, was purposely chosen for the Manhattan Project because he was hard-nosed and, in pursuit of a goal, was not picky about whose toes he stepped on. He “drafted” industrial magnates and PhDs like so many army privates, lectured them, or shouted at them on occasion. He upstaged Congress, trusted absolutely no one, and coaxed incredible sums of money from the U.S. Treasury without being able to disclose for what he was using the funds.

Groves was especially strict on security. He would scold famous scientists for any real or perceived violation of secrecy. Mail was censored, telephone calls monitored, scientists shadowed after they left the laboratory.

Because a large number of funerals in the boomtown of Oak Ridge might tip off lurking spies that something big was going on, there were no new mortuaries in the city. In the research laboratory area, the garbage and trash-collection companies hired only illiterates so that if they found classified material, they would not be able to read it.

As far as most of the outside world was concerned, wartime, bustling Oak Ridge would be a noncity. Security was so tight that no German or Japanese agent would ever know about the crucial installation.

22

“Hello, America! Berlin Calling!”

H

OME-FRONT AMERICA WAS SHOCKED

on July 26, 1943, to hear stories on radio and read them in newspapers that six United States citizens were indicted in absentia by a grand jury in Washington, D.C., on charges of wartime treason, which called for the death penalty. The six Americans had been broadcasting German propaganda to America on shortwave radio.

Those charged by the U.S. Justice Department were Jane Anderson, Robert Best, Fred Kaltenbach, Constance Drexel, Douglas Chandler, and Edward Delaney. They had been living in the Third Reich or had arrived there shortly after war erupted in Europe in September 1939. They were accused of being commentators on the Die Deutschen Überseesender (German Overseas Stations), which was located in Berlin and had twenty-three powerful transmitters scattered around Germany.

Eight newscasts were beamed each day, at hourly intervals, to the United States, where hundreds of thousands of citizens had shortwave radio receivers. Paul Josef Goebbels, the diminutive, brainy, Nazi propaganda chief, had recruited the six Americans to replace the German commentators. Goebbels thought the propaganda would be more believable if spoken in “American English” by genuine Americans.

Most of the broadcasts began with an upbeat voice calling out: “Hello, America! Berlin calling!”

In charge of the North American zone of the German radio network was Kurt von Boeckmann, who held a law degree from Heidelberg and had served as a captain in the German Army during World War I. He began his radio career as an advisor for a Bavarian radio station and became its Intendant (chief executive) a few years later. In 1933, he was appointed to his current post.

Von Boeckmann was a mysterious figure. When Adolf Hitler sent his legions plunging into neighboring Poland to ignite what would become a global conflict, the broadcaster requested prompt retirement. Later reports would surface that he was a key figure in the Schwarze Kapelle (Black Orchestra), a secret movement headed by prominent German military, government, and civic officials, whose goal was to get rid of the führer. The request was denied.

Knowing that the Geheime Staatzpolizei (Gestapo) would be watching his every move and gesture, von Boeckmann went about his work with vigor. Perhaps the best of his American recruits was Frederick W. Kaltenbach, who was born in Dubuque, Iowa, the son of an immigrant German butcher.

In 1920 Kaltenbach received a BA degree from Iowa State Teacher’s College, then took an MA at the University of Chicago before accepting a job as a school principal in his hometown of Dubuque. Soon after Adolf Hitler had seized total power in Germany in 1932, Kaltenbach visited the Third Reich and was greatly impressed with the promise of National Socialism (Nazism).

“Hello, America! Berlin Calling!”

131

Only a few weeks after his return to Dubuque, the school board fired him for organizing a Hitler Youth kind of club on the high school campus. That event resulted in his going to Germany to obtain his doctorate. There he married a young German woman, and in 1939, he began making his first shortwave broadcasts to the United States, using the name Fred W. Kauffenbach.

The cultured Kaltenbach loaded his propaganda broadcasts with potshots at Allied leaders, referring to the American president as “Emperor Roosevelt I, who aspires to be the Lord of the Universe.” Compared with Roosevelt, “Benedict Arnold was a mere piker. All he did was to betray a fort to the Red Coats [British]. Roosevelt has betrayed the whole country,” Kaltenbach exclaimed.

Jane Anderson, who had been born in Atlanta, Georgia, came to Berlin in early 1941 with a journalistic background. During World War I, she had made a name for herself as a daring reporter covering the Western Front for the London Daily Mail.

In the early 1930s, Jane married a wealthy Spanish aristocrat, the Marquis Alvarez de Cienfuegos, an act that gave her the royal title of marquesa. With the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936, she again served as a correspondent for the Daily Mail. She was captured by Spanish government forces, charged with spying for the Nationalists of General Francisco Franco, and was held in a dirty Madrid prison for six weeks.

Anderson managed to slip a message to the U.S. embassy, which intervened and secured her release, with the provision that she promptly leave Spain.

Anderson hurried to Paris to be reunited with her husband, then she left for the United States to launch a lecture tour that focused against Communism. She described in detail the horrors of her jail time under the Communists. Americans adored her. She was proclaimed by the Catholic Digest as the “world’s greatest orator against Godless Communism.” Time quoted the noted Monsignor (later Bishop) Fulton Sheen as describing her as a “living martyr.”

After her lecture tour in 1939, Anderson returned to Europe, where she was recruited by Josef Goebbels, who had noted in his diary that she had been a “big sensation in New York.” In her first broadcast to the United States, she compared Adolf Hitler to Moses: “He has reached to the stars, and the Lord’s will would prevail.”

Not all listeners on home-front America were enthralled with Anderson’s propaganda broadcasts. One New York City newspaper declared: “If her microphone hysteria is a clue to her personality, she is probably mentally unhinged.”

Be that as it may, Anderson’s broadcasts became even shriller after Adolf Hitler declared war on the United States in early December 1941. “So the American people have gone to war to save [Josef] Stalin and the Jewish international bankers,” she exclaimed. She charged that Roosevelt was in constant contact with the “Red Antichrist” [Stalin], who “is beating children black and blue for their religion.”

In March 1942, Anderson was setting her American audience straight on the reported German food shortage by describing her visit to a posh Berlin restaurant: “On silver platters were sweets and cookies, a delicacy I am very fond of. My friend ordered great goblets filled with champagne, into which he put shots of cognac to make it more lively. Sweets, cookies, and champagne! Not bad!”

British propaganda experts rubbed their hands in glee. Anderson’s bacchanalian bombast was translated from “American English” into German and radioed back to the Third Reich, where the Herrenvolk (people) were feeling food pinches and most knew champagne as only a hazy memory.

The impact of the turnaround broadcast was considerable, Allied agents in Germany reported. People were furious that some privileged persons, such as Anderson and Nazi leaders, were gorging themselves while the plain people were scrounging.

Jane Anderson disappeared from the airwaves.

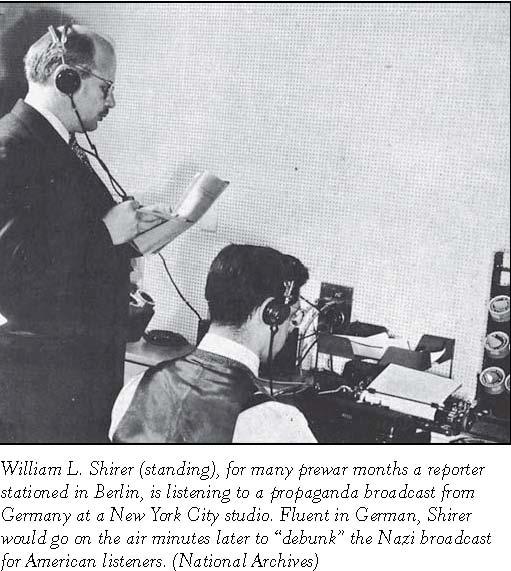

William L. Shirer, a prominent American journalist who covered the Berlin beat in the years before the United States got involved in the global conflict, described Edward Delaney, another of the broadcasters, as being a “very mild fellow” but one consumed with a “diseased hatred for Jews.”

“Hello, America! Berlin Calling!”

133

Delaney was born in Olney, Illinois, to Irish immigrants; he spent most of his youth in Glenview, a suburb of Chicago, and launched a career on the stage, traveling the world with a road company.

After the stock market crash of 1929, Delaney was jobless. When he was invited to Berlin in August 1939, after his anti-Jewish views were noted by the German embassy in Washington, he was offered a job countering anti-Nazi propaganda overseas. He began broadcasting to the United States using the name E. D. Ward.

In one broadcast Delaney told Americans that there was a plan afoot to install the Duke of Windsor [the abdicated king of England] as first viceroy in Washington, “a sort of assistant to President Roosevelt—or would Roosevelt be subordinated to him?”

No doubt the most inept of the indicted six was Constance Drexel. William Shirer said of her: “The Nazis hired her principally because she was the only woman in [Berlin] willing to sell her American accent to them.”

Born in Darmstadt, Germany, Drexel’s parents brought her to Roslindale, Massachusetts, when she was an infant. After attending several schools in the United States, she eventually obtained her degree from the prestigious Sorbonne in Paris. Constance returned to America in 1920 and, for the next two decades, she worked for several newspapers.

In May 1939, Constance quit her job and left for Germany, telling friends she wanted to visit relatives. A year later, she began broadcasting to America on German radio, which introduced her as “the famous American journalist” and as a “Philadelphia socialite and heiress.”

It was not long before Drexel fell from grace, and top Nazis began avoiding her. She had pulled a monumental faux pas while attending a reception for Party leaders. On being introduced to a beautiful young German woman, Constance blurted: “Oh, you are the girlfriend of Adolf Hitler!”