The Annals of Unsolved Crime (26 page)

Read The Annals of Unsolved Crime Online

Authors: Edward Jay Epstein

My own assessment, after considering the evidence made available to me in London, Washington, D.C., and Moscow, is that Litvinenko was likely contaminated by accidental leakage of polonium-210. If so, his death would be consistent with all the known previous cases of polonium poisoning in France, Israel, and Russia. Such a leak would be even more likely if a vial was handled outside a lab because polonium-210, which can turn into a gas because of the heat produced as it decays, has a propensity to leak from containers. To be sure, polonium-210 is not readily available, other than to people in rarified professions, such as nuclear scientists, smugglers, and intelligence operatives. As for the latter category, Litvinenko was involved with a number of intelligence services, including British intelligence, Russia’s FSB, America’s CIA (which rejected his offer to defect in 2000), and Italy’s SISMI (which was monitoring his phone conversations). One way that an intelligence service might use polonium-210 is in a battery for a miniature transmitter used to track a person of interest. Another way would be to use it in an intelligence game as a sample in an exchange to entrap someone suspected of buying nuclear components.

The British government has gone to considerable lengths to conceal Litvinenko’s relationship with its intelligence services (even delaying the coroner’s report for, as of this writing, six years). Other intelligence services have no doubt also made sure that their dealings with Litvinenko will not surface. But we know Litvinenko and a number of his associates, whether wittingly or not, were in contact with a container of polonium-210. My conclusion is that it leaked.

We will never know how or why Litvinenko came into contact with this substance, because all the evidence that might answer our questions, such as the autopsy report, is locked

away in the realm of national-security secrecy. A British inquest may reveal further details of the crime, but in the cases of such sensitive political crimes, evidence that vanishes seldom reappears in a creditable form. As a result, the radioactive death of Litvinenko likely will remain an unsolved crime.

CHAPTER 28

THE GODFATHER CONTRACT

On March 20, 1979, Carmine “Mino” Pecorelli, a fifty-year-old journalist who was paid not to publish unsavory news in his scandal sheet, was assassinated in his office on the Via Orazio in Rome. When the gunman entered, Pecorelli was editing the next week’s issue of his

Osservatorio Politico

. The assassin killed him with four well-placed bullets, and, Mafia-style, left the shell casings next to the body. The casings established that the bullets were of the Gevelot brand, which is not commonly used. The Gevelot brand was used, however, by an organized group of killers called the Magliana gang. The police assumed that this was a professional contract killing, and learned from their informers in the Rome underworld that the contract to kill Pecorelli had come from the Sicilian Mafia. At the time, there was no shortage of people with a motive. Any of the well-connected politicians and power brokers that Pecorelli was either blackmailing or threatening to expose could have put a contract out on him. In view of this surfeit of motives, and the lack of witnesses to the murder itself, the police did not pursue the case.

After fourteen years, however, a sensational lead emerged that would strike at the heart of the Italian political establishment. It came from a Mafia “pentito,” or former Mafia member who was now cooperating with the police in return for leniency. This turncoat was Tomasso Buscetta, and on April 6, 1993, Italian investigating magistrates announced that

Pecorelli’s murder contract had been arranged by the Mafia on behalf of one of Italy’s most important political leaders, Giulio Andreotti. Buscetta said that Andreotti wanted to eliminate Pecorelli because Pecorelli was planning to publish documents that would implicate Andreotti in the death of former Prime Minister Aldo Moro, who was kidnapped by the Red Brigade in 1978, held in captivity for sixty-four days, and then executed. The request came to the Mafia via two Sicilian politicians, according to Buscetta.

If there was a political Godfather of postwar Italy, it was Andreotti. He had served as Prime Minister three times between 1972 and 1992. He also had been minister of the interior in 1954 and 1978, defense minister from 1959 to 1966 and again in 1974, and foreign minister from 1983 to 1989. He had made the Christian Democratic party into America’s key ally in Italy. Even though many of his colleagues had been indicted in the infamous Tangentopoli, or “bribe city,” in the early 1990s, Andreotti was not himself implicated and was elected a senator for life.

Now he was accused of complicity in murder. His accuser, Buscetta, had had a bloody criminal career in the Mafia. He was a major heroin trafficker in South America and implicated in two murders in the United States. After being extradited to the United States from Brazil in 1984, he agreed to provide information to U.S. authorities about Mafia activities in return for his freedom, and was subsequently given a new identity and put into the U.S. Witness Protection Program. According to Buscetta, Andreotti had been the Mafia’s “man in Rome” for decades, using his immense power to “adjust,” or reduce, Mafia prison sentences. In return, the Mafia, according to Buscetta, did his dirty work, which included murder. Buscetta himself did not claim to have ever met or even seen Andreotti. His allegations proceeded from stories relayed to him by other Mafia members, all of whom were either dead or silent.

Two separate magistrates, one in Rome, the other in Palermo, were unable to even establish that Andreotti, or any of his associates, had ever adjusted any Mafia sentences, so the magistrates developing the case relied on the accounts of two other imprisoned pentiti. Both of these men had been convicted of murder, and by testifying against Andreotti, they both literally got away with murder.

The first witness was Baldassare Di Maggio, who had admitted murdering fifteen people before he was arrested in 1993. He alleged that in September 1987 he had witnessed Andreotti receive a “kiss of honor” from the top Mafia leader in Sicily, Toto Riina, in the Palermo apartment of Sicilian politician Ignazio Salvo. There were two immediate problems with his story. For one, the entrance to Salvo’s apartment was guarded by police because Salvo was under house arrest in September 1987, so it seemed highly unlikely that Riina, who was then the most wanted fugitive in Sicily, would choose a venue under police surveillance for a Mafia gathering. Second, Andreotti was foreign minister in 1987 and had a twenty-four-hour security detail that kept detailed records, which do not show that Andreotti was in Palermo at the time of the meeting. To attend, he would have had to elude his security detail. As the inquiry proceeded, Di Maggio’s credibility was further damaged when investigators discovered that he had committed a murder after he had been admitted to the Italian witness protection program and then falsely claimed that he had been given permission to commit the homicide by Italian authorities. The investigating judges concluded that Di Maggio’s “kiss of honor” story was a total fiction. The other witness in 1993 was Marino Mannoia, who claimed that in 1980 he had personally witnessed Andreotti arrive in a bulletproof Alfa Romeo sedan at a villa in Sicily in the company of several Mafia leaders. Since none of these leaders was alive, there were no witnesses who could confirm or disprove the putative meeting. In addition, Mannoia was

unable to recall the exact place or date of this alleged meeting, so his story could not be checked against the records of Andreotti’s security detail. Aside from these two witnesses, the magistrates heard a number of secondhand stories recounted in prison. While such hearsay testimony is ordinarily not admissible in court because it denies the accused the ability to confront the accuser, the magistrates made an exception here on the grounds that “one of the inflexible rules of the Mafia is that men of honor must tell the truth when speaking of facts relating to other men of honor.” This rule turned out to be flawed, because one of the hearsay stories told by Buscetta about a Mafia heroin trafficker proved to be untrue.

For his part, Andreotti denied all the charges and pointed out that the Mafia had reason to discredit him. He had been personally responsible for initiatives against the Mafia, such as the international bilateral agreements that allowed the United States to extradite mafiosi (including Buscetta); the Decree-laws that prevented the release of Mafia suspects before trial; and the dissolution of twenty-nine Mafia-penetrated municipal councils in Sicily. His party had also passed laws allowing the internal exile of Mafia suspects without trial, which led the Mafia to engage in a full-scale attack on civil authorities in the early 1990s and blowing up anti-Mafia investigators.

In 1996, Andreotti was formally charged, on the basis of the pentiti evidence, with complicity in Pecorelli’s murder, and, after a long trial, fully acquitted. In Italy, the prosecution can appeal jury verdicts, and in an appeal the verdict was overturned, and Andreotti was convicted of complicity of murder in 2002. But then that verdict was quickly overturned by the superior appeals court, and Andreotti was again declared innocent. As a result of these trials, the murder of Pecorelli remains an unsolved crime.

Almost all the theories about the murder proceed from possible motives. Since Pecorelli had been in the political-blackmail

business for a decade, it is not difficult to identify parties that might have a reason to put out a contract on his life. The theory that Andreotti was the culprit has persisted even after his acquittal. The 2008 movie

Il Divo

makes the case that Andreotti’s allies in Sicily had made deals with the Mafia to win elections, and that they used the Mafia to eliminate Pecorelli when he threatened to link Andreotti to the death of Moro. Other theories focus on groups involved in major scandals in the late 1970s, such as Licio Gelli’s Propaganda Due lodge (of which Pecorelli was reportedly a member), the Gladio paramilitary networks, and the beneficiaries of the secret accounts in Panama of the Banco Ambrosiano. Indeed, almost any shadowy group with a secret to hide could be considered to have a motive in silencing Pecorelli.

My own assessment is based on documents that I received in Rome from lawyers involved in the case against Andreotti. From them, I conclude that the charges against him were politically motivated and with little, if any, basis in fact. The most likely killer of Pecorelli is one of the individuals from whom he was attempting to extort a price for his silence. Such a party, rather than paying him for his silence, could have decisively gained his silence by having him killed.

The lesson is that while it is possible to elicit stories from sociopaths, especially if they are provided with incentives, the resulting testimony cannot be relied on in the service of truth. Magistrates concocted the case against Andreotti almost entirely out of Mafia turncoat stories that could not be corroborated. Almost all of it was hearsay, allowed because of the myth that ex-Mafia men cannot lie to one another. Yet, this myth is refuted by numerous cases in which Mafia members have lied to each other. By casting suspicion on the man responsible for the extradition agreement with America, they diverted attention from others in the Mafia who were their criminal allies.

CHAPTER 29

THE VANISHINGS

In the 2004 film

The Forgotten

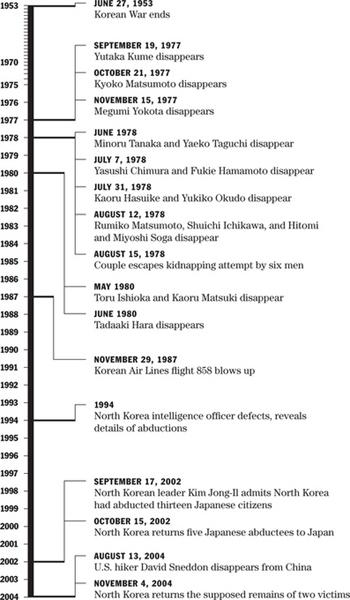

, a seemingly delusional mother played by Julianne Moore discovers that the government is part of an elaborate conspiracy to abduct children. Even in the fictional realm of Hollywood, this notion of alien abduction might have qualified as the height of political paranoia, but that same year, Japanese parents whose children had left home and disappeared in the late 1970s and early 1980s learned that the children had been systematically abducted by an alien state, North Korea. This revelation came in September 2002 when Kim Jong-Il, North Korea’s supreme leader, admitted to Japanese Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi that his intelligence service had carried out abductions of Japanese youth. What remained a mystery even after the admission of this political crime was how many people were kidnapped in this state-sponsored program, and why.

Initially, police in Japan understandably viewed these vanishings as isolated incidents. After all, the 1970s in Japan, as in the United States, was a time of drugs, rock music, and youth rebellion, and missing youth were not necessarily victims of forcible abductions. When parents persisted in believing that their children had been kidnapped, they themselves were often considered out of touch with reality.

One such incident occurred in the rural prefecture of Niigata on the Sea of Japan. On November 15, 1977, Megumi Yokota, a thirteen-year-old student, left badminton practice at school, and never arrived home. The local police conducted a massive search for her, and they called in a team of underwater divers to scour areas along the shore in which she might have drowned. They found no trace of her. Nor did any witnesses come forward when her photo was published in local newspapers.