The Arrogance of Power (23 page)

Read The Arrogance of Power Online

Authors: Anthony Summers

“I knew,” Nixon wrote in the seventies, “how much it had hurt her, how deeply it had wounded her sense of pride and privacy. I knew that from that time on, although she would do everything she could to help me and help my career, she would hate politics and dream of the day when I would leave it behind. . . .”

And then there was Mother. Hannah Nixon played an unusual role in the fund crisis, one that most adult sons would surely have regarded as an outrageous intrusion. She had been in Washington baby-sitting the girls, then aged six and four, when the story broke in the newspapers. Her husband, Frank, like his son, had been reduced to bouts of weeping. Hannah began a series of long-distance calls to Pat and, along with the telegram to her son, composed another to General Eisenhower himself. It read:

I AM TRUSTING THAT THE ABSOLUTE TRUTH MAY COME OUT CONCERNING THIS ATTACK ON RICHARD

.

WHEN IT DOES I AM SURE YOU WILL BE GUIDED ARIGHT IN YOUR DECISION TO PLACE IMPLICIT FAITH IN HIS INTEGRITY AND HONESTY

.

BEST WISHES FROM ONE WHO HAS KNOWN RICHARD LONGER THAN ANYONE

.

HIS MOTHER

,

HANNAH NIXON

Eisenhower read the telegram aloud in public the night he welcomed Nixon back into the fold.

Four months later, on January 19, 1953, as the Nixon family gathered for a private dinner on inauguration eve, Nixon's mother took him aside and handed him a small piece of paper bearing the following message:

To Richard

You have gone far and

we are proud of you alwaysâ

I know that you will keep

your relationship with your

maker as it should be

for after all that, as you

must know, is the most

important thing in this life

With Love Mother

“I put it in my wallet,” Nixon wrote of the note, “and I have carried it with me ever since.” Soon enough it was joined there by a brief memorandum to himself that Nixon wrote at Pat's request. He would retire from politics, he was to promise her, at the end of his first term as vice president, in 1956. He had put the assurance in writing, as if to emphasize that it was unbreakable. “But,” as Pat said years later, “things took a different turn.”

_____

Nixon used an ancient family Bible, an heirloom brought along by his mother, at his inauguration as vice president. As a Quaker he had the right to substitute the word “affirm” for the word “swear”âQuakers have a religious objection to swearing any oathâbut he chose the standard phrasing and, with his Quaker parents close by, intoned: “I, Richard Nixon, do solemnly swear that I will support and uphold the Constitution. . . .”

His hand rested on a passage from the Sermon on the Mountâ“Blessed are the peacemakers: for they shall be called the children of God”âwhich may have been intended as a nod to the Quakers' guiding precept of Peace at the Center. Certainly, in the years that followed, Nixon was to assert that his life's deepest desire was to bring peace between nations. In the eight years he served Eisenhower as vice president, he was to travel the world more than any American leader had done before, building up a breadth of knowledge on international affairs unequaled in his time.

At forty Nixon was the youngest vice president in nearly a century. On that January day of his first inauguration, the head of his Secret Service detail thought, the look on his face was one of “exaltation.”

Yet even then there were portents. Some of those who would feature in his future disgrace had already crossed his path. A few months earlier, as Nixon

arrived at the studio to make the Checkers speech, one of the Young Republicans cheering him on had been twenty-five-year-old H. R. Haldeman. His father, car dealer Henry Haldeman, had been a contributor to the fund. During the campaign a teenager called Lucy Steinberger had had the chutzpah to ask Nixon for an interview when he visited her high school in Virginia; under her married name, Lucianne Goldberg, she would become better known. The revelation of her work as a sex spy for the Nixon White House gave her a bit part in the Watergate saga. In 1998, in a not dissimilar function, she orchestrated the exposure of President Clinton's sexual adventures with Monica Lewinsky.

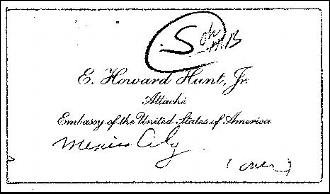

It was also probably in 1952 that Nixon met a much more significant Watergate player, E. Howard Hunt. Then a young CIA officer, he had come over to Nixon's table at Harvey's restaurant in Washington, discussed politics for a while, and left his calling card. “My wife and I,” Hunt scrawled on the back of the card, some twenty years before he was to lead the raid on the Democratic party headquarters in the Watergate building, “want to thank you for the magnificent job you're doing for our country.”

*

11

In his function as vice president, Nixon would soon officiate at the swearing in of a new U.S. senator for North Carolina, Sam Ervin. He was the man whom President Nixon, on the Watergate tapes, would characterize as an “old shit,” the man who, as the magisterial chairman of the Senate Watergate Committee, earned the affections of millions when he presided over the ruin of Richard Nixon.

Back in the fifties Ervin had felt “Somewhat cool” toward the young man officiating at the ceremony. He did not like what he had heard about his election tactics.

Handsome and kind, Handsome and kind,

Always on time, Loving and Good.

Does things he should, Humerous, funny

Makes the day seem sunny, Helping others to live,

Willing to give his life, For his belovd country,

That's my dad.

âJulie Nixon's poem for her father, written in 1956, when she was eight and he was vice president

O

ne evening in 1954, after martinis and steak at Duke Zeibert's Restaurant in Washington, Nixon slumped back amid the plush and gold plate of his official limousine. “This,” he said wearily, patting the upholstery, “is the only thing about the goddamn job I like. Except for this, they can have it. . . .”

Eighteen months into his term of office his exaltation about the vice presidency had turned to despond. His companion in the limousine that night was James Bassett, the political journalist on loan from the

Los Angeles Mirror

who was to manage his press relations and scheduling for years to come. Bassett, a bespectacled navy veteran just three months older than Nixon, served as adviser, political sounding board, and drinking companion. His letters home to his wife, Wilma, offer a rare, intimate glimpse of the private Nixon.

Bassett had thought Nixon “quietly intense” but “affable” when he first met him six years earlier and had jokingly used his minuscule seniority to

address Nixon as “son.” Now, he reflected, he barely recognized him. Nixon, he wrote his wife, had become “the oldest young man I ever saw. . . . Sometimes I feel like a doggoned kid when I'm around him.”

Nixon preferred to do his real work not in his ceremonial headquarters or in his staff suite in the Senate complex but in P-55, a remote room in the Capitol building that few knew how to find. While Bassett had always respected his “judgment and ability,” he thought he had grown more intense than ever. “The man never rests, relaxesâI guess he takes politics through his pores, the way a leaf gets chlorophyll.”

Nixon told Bassett he was one of those politicians with “ice water in our veins,” but he sometimes showed a “subliminal sentimental streak.” “I'd met him for lunch somewhere in uptown Washington,” Bassett wrote, “and he was carrying with him a clumsily wrapped paper parcel. âIt's a doll,' he explained, although I hadn't asked. âFor Julie and Tricia?' âNo,” Nixon frowned. âIt's actually for a little crippled kid I happened to read about in the paper this morning. She's in a charity hospital. It said she wanted a doll. So I'm going to take this out to her after we've finished.'Â ”

Ever the PR man, Bassett thought the gift would make good press. But Nixon would have none of it. “If you ever leak this to the newspapers,” he threatened, “I'll cut your balls off.”

Nixon seemed to Bassett to be a loner with a tendency to “retreat deeper into that almost mystic shell.” He rarely went home in the evening and, because Bassett was living in Washington away from his own wife and family, would call him on the spur of the moment to suggest dinner. In these, his “lonesome lost moods,” Nixon shed some of his “grimness and glacial determination” and did some companionable drinking.

Bassett's account establishes that Nixon's somewhat pious writing about drink in later years and loyalists' protestations that he rarely drank are hypocritical. Himself no stranger to liquor, Bassett recalled their bibulous nights. “We ordered extra dry Gibsons (with Nixon darkly muttering it was a âgreat mistake'). Then a second round. Then RN, having relaxed enthusiastically, briskly demanded a third, all his darkling fears apparently gone. Then a sound California Inglenook white Pinot, oysters and baked pompano. . . . In RN's fabulous Cad, we tooled out to a place called Martin's in old Georgetown, a saloon-type café, where we feasted on corned beef, cabbage, and great drafts of Michelob. . . . We had Scotches. RN took two of them fast, heavy and straight, thereby heightening his curious mood.”

Sometimes the drinking was a feature of the working day. Bassett again: “We'd arrived earlier for lunch than usual, and prowled through his desk for a jug of Scotch, but finding only a platoon of very defunct soldiers; then RN arriving with Rose Woods in tow, and she laden with a small box in which nestled the necessaries of any decent midday confab.”

In 1952, the year

Time

reported the official line that Nixon “rarely takes a drink,” the Democrats' financial wizard Carmine Bellino had visited him. “At

about 5

P

.

M

.,” he recalled, “Nixon stated it was cocktail hour. He pulled open his desk drawer, took out a bottle of scotch, and called Rose Woods to bring three glasses. After pouring scotch into the glasses, he offered us a drink without ice. . . .”

Elmer Bobst, the pharmaceutical tycoon, advised Nixon in the fifties to put a bottle of scotch in his briefcase if he wanted to avoid losing it. “Scotch, or perchance gin,” he wrote, “are [

sic

] wonderful catalysts blending together memory and briefcases.” Nixon apparently did develop a liking for gin. Bobst recalled how they once both pretended to order plain tonic water to avoid offending an accompanying cleric; that the well-trained barman would add gin to it.

In 1954, the year Bassett spent the most time with Nixon, an article based on a personal interview with the vice president reported that he “won't drink at all if he's tangling with a problem.” However, Bassett's accounts suggest that like other mortals, Nixon used alcohol precisely when he was confronting a difficult issue.

Drink affected him easily and perhaps more so as time passed. Bassett remembered spending “a most curiously interesting couple of hours” with his boss in the late fifties, when he “let his thinning hair way down over a few Scotches.” Bassett reported, as did others, that “after two Martinis he'd be very garrulous . . . two drinks and he's off to the races.”

Nixon on occasion became obviously the worse for wear in lofty company. “Nixon had a glass or two more than he should have done,” Pat Hillings recalled of an evening with the Eisenhowers shortly before the start of his vice presidency. “It didn't really show until he came down in the elevator, but then he startled everyone by giving the wall a smack and saying at the top of his voice, âI really like that Mamie. She doesn't give a shit for anybodyânot a shit!'Â ”

Nixon may have genuinely liked Mamie, but his relationship with Ike remained ambivalent.

_____

At the start of the Eisenhower administration some dubbed Nixon “Ike's errand boy.” The sneer was not unexpected because the post of vice president of the United States had traditionally been one with an imposing name but no real power. Eisenhower needed Nixon to keep the Republican right on his side and, not least, to help contain the erratic Joe McCarthy. At sixty-three, he also needed a younger man to carry the burden of hard campaigning and foreign travel. Nixon took on all those responsibilities, and his marathon trips abroad were the foundation of the foreign policy expertise that remains his most positive legacy. What Eisenhower did not want, however, was for Nixon to be perceived as playing the role

Life

magazine proposed early on: “Assistant President.”

While the two men were publicly civil to each other, Eisenhower went out of his way to keep Nixon at arm's length. Lyndon Johnson, then a rising power in the Senate, recalled Eisenhower's resentment when Nixon tried discreetly to

influence policy. According to James Reston, the

New York Times

journalist, Eisenhower “simply was not interested in Nixon's view of things.” He reportedly found him “immature” and would still be describing him as such as late as the sixties, after Nixon had turned fifty.

Some at the White House thought Nixon more liability than asset, and the scorn was reciprocated. In private, drinking with Bassett, Nixon spoke contemptuously of the “tea drinkers” surrounding the president. He dismissed the cabinet as “dumb.” When he went on television to help distance the White House from Joe McCarthy, though, he smiled for the camera as Eisenhower had urged him to.

Shortly before that speech, while quaffing bourbon with Bassett, Nixon had made a remark that today resonates with irony. “He said wistfully,” Bassett recalled, “that he'd love to slip a secret recording gadget into the President's office, to capture some of those warm, offhand, greathearted things the Man says, play 'em back, then get them press-released. . . .” Curiously enough, two decades before Nixon was to install secret recording equipment in his White House, Eisenhower had recording equipment set up in the Oval Office, a device he activated with the flip of an unseen switch under his desk.

With Nixon present, Eisenhower urged senior colleagues to tape their phone calls. “You know, boys,” he said, “it's a good thing, when you're talking to someone you don't trust, to get a record made of it. There are some guys I just don't trust in Washington, and I want to have myself protected so that they can't later report that I said something else.” According to one Nixon biographer, Eisenhower “nearly always remembered to turn on the machine when he was talking to Nixon.”

1

The transcript of one such recording, made in June 1954, shows Eisenhower castigating his vice president for a speech in which he had attacked Democratic foreign policy. The president bluntly told Nixon that he was wrong on his facts and was compromising White House efforts to build bipartisan support. Having promised to be more circumspect in future, Nixon was so depressed afterward that Bassett thought him “lower than a snake's belly.” In his memoirs Nixon would suggest he had had a collegial relationship with Eisenhower. Privately he told Haldeman that he “saw Dwight D. Eisenhower alone about six times in the whole deal. . . .”

Political issues aside, Nixon suffered many small humiliations. Eisenhower loved golf and often played at the exclusive Burning Tree Club in the Maryland countryside. Nixon, usually more spectator than sportsman, now took up golf energetically. While he reportedly played with “furious dedication,” he lacked skill or finesse. It was even reported that he cheated on occasion, by throwing the ball out of the rough back onto the fairway.

Once, on an excursion with Bassett, Nixon went to Burning Tree on a day Eisenhower was playing. “Nixon fired off the tee firstâa wobbly shot into the woods. He hit six in all. Then the others, and by this time Ike and his party were breathing on our group's necks. So, after some slight Alphonse and

Gastoning, the presidential group went through. . . . We lunched at one of the long communal tables. . . . The president sat at the adjoining table, grinning, laughing and joking, with

his

foursome.”

“Nixon complained to me,” recalled Walter Trohan, “that Ike didn't have him in to play golfâI guess his game wasn't good enough. Ike played with pros.”

2

Nor were invitations extended to play bridge with the president or to attend social evenings in the private quarters of the White House.

3

Four years into the presidency, out at the president's Gettysburg farm, Nixon watched as Eisenhower escorted other guests indoors. “Do you know,” he told a companion bitterly, “he's never asked me into that house yet.”

4

Nixon spoke to Dr. Hutschnecker, the psychotherapist, about his resentment. According to the doctor, “Eisenhower was always telling Nixon to straighten his tie or pull back his shoulders, or speak up or shut up.”

The conservative writer Ralph de Toledano thought Eisenhower was a “complete sadist” toward Nixon. “He would cut him up just for the fun of it. . . . Nixon would come back from the White House and, as much as he ever showed emotion, you'd think he was on the verge of tears.”

Not only the president spurned Nixon at this time. In the spring of 1954 he was rebuffed by both the educational institutions at which he had once excelled. The Duke University faculty, in its first ever such action, turned down a trustees' proposal that Nixon be awarded an honorary Doctorate of Laws. When officials called a second meeting, in hopes of getting the decision reversed, Nixon was again rejected. Weeks later, when he gave the commencement address at his alma mater, Whittier College, students formed two reception lines: one for those who refused to shake Nixon's hand, one for those willing to greet him. Only two were in the latter group, and Nixon's mother declared herself “pained.”

In Washington, meanwhile, Nixon was making few friends. At a party the Nixons gave, CBS reporter Nancy Dickerson recalled, “he was an uncomfortable host, disappearing from time to time, only to return to urge guests to have another drink, with a vigorous show at being friendly. Being a host did not come easy for him.”

Patricia Alsop, the English wife of columnist Stewart Alsop, found the Nixons “wooden and stiff . . . terribly difficult to talk to” when she invited them to one of her soirees. “Nixon danced only one dance, with me. He was a terrible dancer, and Pat didn't dance at all. They stayed only half an hour. It was like having two little dollsâor as if the school monitor had suddenly appeared at the dance. I couldn't wait for him to go.”

Stewart Alsop noted that Nixon often sparked an almost allergic dislike in people, including many Republicans. Those who did not think Nixon worthy of a halo, the columnist observed, tended to ascribe to him cloven hooves and a tail. Alsop coined a term for this condition, one that remained chronic for forty years to come: Nixonophobia.