The Assassins (15 page)

Authors: Bernard Lewis

Tags: #History, #World, #Political Science, #Terrorism, #Religion, #Islam, #Shi'A

Hulegu on his way to capture the Ismaili castles in the year 654/1256. From a Persian manuscript of the Jami al-tavarikh, in the library of the Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal, Calcutta; ca. A.D. 1430.

Hulegu. From an album of drawings in the British Museum (Ms. Add. 18803).

An inscription on the wall of the castle of Masyaf, in Syria. 13th century.

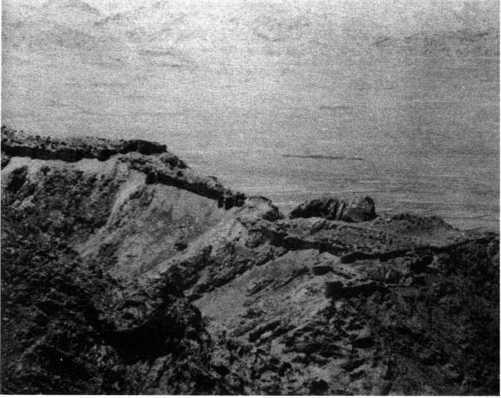

An aerial view of the massive Assassin castle of Qa'in.

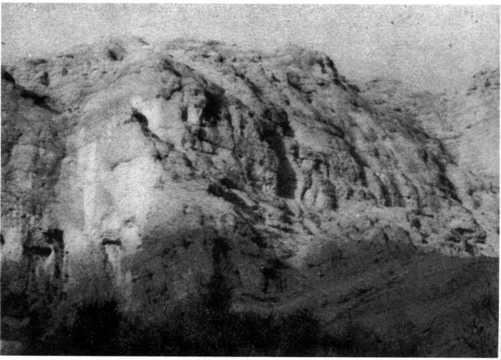

A closer view of the walls of Qa'in.

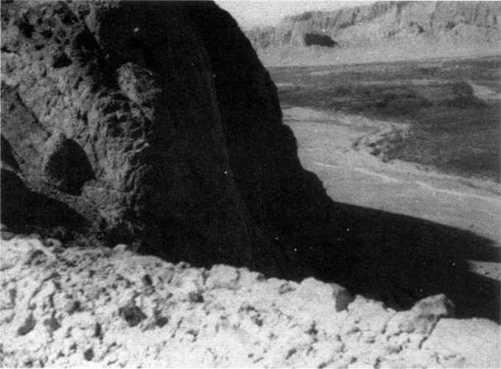

The castle of Lamasar.

The rock of Alamut, with the castle on its crest.

The Assassin stronghold of Maymundiz.

View of the valley from Qal'a Bozi, near Isfahan.

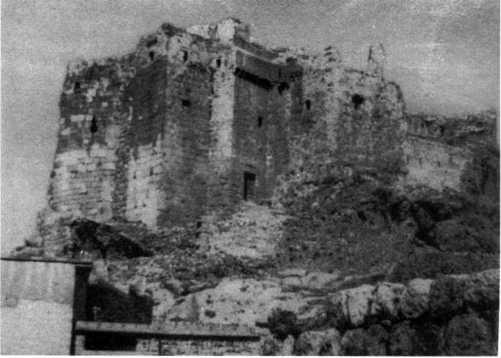

The castle of Masyaf.

Entrance to the citadel of Aleppo.

Whatever understanding may have existed between the Ismailis and the Mongols, it did not last. The new masters of Asia could not tolerate the continued independence of this dangerous and militant band of devotees - and there was no lack of pious Muslims among their friends and associates to remind them of the danger which the Ismailis presented. The chief Qadi of Qazvin, it is said, appeared before the Khan in a shirt of mail, and explained that he had to wear this at all times under his clothes, because of the ever-present danger of assassination.

The warning was not wasted. An Ismaili embassy to the grand assembly in Mongolia was turned away, and the Mongol general in Iran advised the Khan that his two most obstinate enemies were the Caliph and the Ismailis. At Karakorum precautions were taken to guard the Khan against attack by Ismaili emissaries. When Hulegu led his expedition into Iran in 1256, the Ismaili castles were his first objective.

Even before his arrival, the Mongol armies in Iran, with Muslim encouragement, had launched attacks on the Ismaili bases in Rudbar and Quhistan, but achieved only a limited success. An advance in Quhistan was repelled by an Ismaili counter-attack, while an assault on the great fortress of Girdkuh failed utterly. The Ismailis in their castles might well have been in a position to offer a sustained resistance to Mongol attacks - but the new Imam decided otherwise.

One of the questions on which Rukn al-Din Khurshah had disagreed with his father was that of resistance or collaboration with the Mongols. On his accession, he tried to make peace with his Muslim neighbours; `acting contrary to his father's disposition he began to lay the foundations of friendship with those people. He likewise sent messengers to all his provinces ordering the people to behave as Muslims and keep the roads secure.' Having thus protected his position at home, he sent an envoy to Yasa'ur Noyan, the Mongol commander in Hamadan, with instructions to say that `now that it was his turn to reign he would tread the path of submission and scrape the dust of disaffection from the countenance of loyalty'.33

Yasa'ur advised Rukn al-Din to go and make his submission in person to Hulegu, and the Ismaili Imam compromised by sending his brother Shahanshah. The Mongols made a premature attempt to move into Rudbar, but were driven back by Ismailis in fortified positions and withdrew after destroying the crops. In the meantime other Mongol forces had again invaded Quhistan, and captured several of the Ismaili centres.

A message now arrived from Hulegu, who professed his satisfaction with Shahanshah's embassy. Rukn al-Din himself had committed no crimes; if he would destroy his castles and come and submit in person, the Mongol armies would spare his territories. The Imam temporized. He dismantled some of his castles, but made only token demolitions at Alamut, Maymundiz and Lamasar, and asked for a year's grace before presenting himself in person. At the same time he sent orders to his governors in Girdkuh and Quhistan `to present themselves before the king and give expression to their loyalty and submission'. This they did - but the castle of Girdkuh remained in Ismaili hands. A message from Hulegu to Rukn al-Din demanded that he attend on him immediately at Damavand. If he could not reach there within five days, he should send his son in advance.

Rukn al-Din sent his son - a boy of seven. Hulegu, perhaps suspecting that this was not really his son, sent him back on the grounds that he was too young, and suggested that Rukn al-Din send another of his brothers to relieve Shahanshah. Meanwhile the Mongols were drawing nearer to Rudbar, and when Rukn al-Din's embassy reached Hulegu, they found him only three days' march from Alamut. The Mongol's answer was an ultimatum: `if Rukn al-Din destroyed the castle of Maymundiz and came to present himself in person before the King, he would, in accordance with His Majesty's gracious custom, be received with kindness and honour; but that if he failed to consider the consequences of his actions, God alone knew [what would then befall him].'34 Meanwhile the Mongol armies were already entering Rudbar and taking up positions around the castles. Hulegu himself directed the siege of Maymundiz, in which Rukn al-Din was staying.