The Assassins (17 page)

Authors: Bernard Lewis

Tags: #History, #World, #Political Science, #Terrorism, #Religion, #Islam, #Shi'A

The history of the Syrian Ismailis, as recorded by the Syrian historians, is chiefly the history of the assassinations which they perpetrated. The story begins on i May 1103, with the sensational murder of Janah al-Dawla, the ruler of Homs, in the cathedral mosque of the city during the Friday prayer. His assailants were Persians, disguised as Sufis, and they fell upon him on a signal from a shaykh who accompanied them. In the melee several of Janah al-Dawla's officers were killed; so too were the murderers. Significantly, most of the Turks in Horns fled to Damascus.

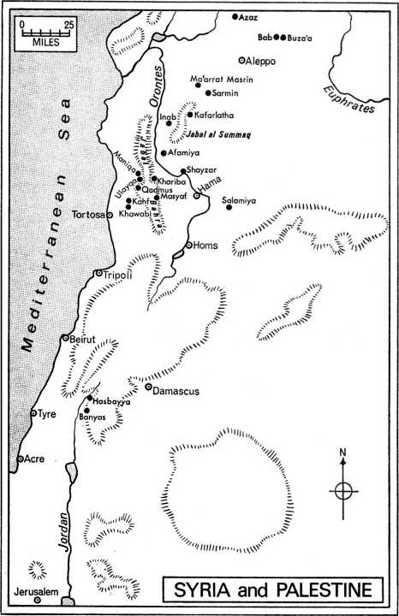

Janah al-Dawla was an enemy of Ridwan, the Seljuq ruler of Aleppo, and most of the chroniclers agree that Ridwan was implicated in the murder. Some gave further details. The leader of the Hashishiyya or Assassins, to use the name by which they were called in Syria, was a personage known as al-Hakim al- Munajjim, `the physician-astrologer'. He and his friends had come from Persia and settled in Aleppo, where Ridwan had allowed them to practice and propagate their religion, and to use the city as a base for further activities. Aleppo had obvious advantages for the Assassins. The city had an important Twelver Shiite population, and was conveniently near the extremist Shia areas in the Jabal al-Summaq and the Jabal Bahra'. For Ridwan, a man of notoriously lax religious loyalties, the Assassins offered the possibility of mobilizing new elements of support, and compensating for his military weakness among his rivals in Syria.

The `physician-astrologer' survived Janah al-Dawla only by two or three weeks, and was then succeeded as leader of the Assassins by another Persian, Abu Tahir al-Sa'igh, the goldsmith. Abu Tahir retained the favour of Ridwan and the freedom of Aleppo, and now made a series of attempts to seize strategic points in the mountains south of the city. He seems to have been able to call on local assistance, and may even have held some localities, though only for a short time.

The first documented attack was made in i io6, against Afamiya. Its ruler, Khalaf ibn Mula'ib, was a Shiite, probably an Ismaili - but of the Cairo, not the Alamut allegiance. In io96 he had seized Afamiya from Ridwan, and demonstrated the suitability of the place by using it as a base for successful and wide-ranging brigandage. The Assassins decided that Afamiya would meet their needs very well, and Abu Tahir devised a plan to kill Khalaf and seize his citadel. Some of the inhabitants of Afamiya were local Ismailis, and through their leader Abu'l-Fath, a judge from near-by Sarmin, were privy to the plot. A group of six Assassins came from Aleppo to carry out the attack. `They got hold of a Frankish horse, mule and accoutrements, with a shield and armour, and came with them ... from Aleppo to Afamiya, and said to Khalaf ... "We have come here to enter your service. We found a Frankish knight and killed him, and we have brought you his horse and mule and accoutrements." Khalaf gave them an honourable welcome, and installed them in the citadel of Afamiya, in a house adjoining the wall. They bored a hole through the wall and made a tryst with the Afamians ... who came in through the hole. And they killed Khalaf and seized the citadel of Afamiya.', This was on 3 February i io6. Soon after, Abu Tahir himself arrived from Aleppo to take charge.

The attack on Afamiya, despite its promising start, did not succeed. Tancred, the crusading prince of Antioch, was in the neighbourhood, and took the opportunity to attack Afamiya. He seems to have been well informed of the situation, and brought with him, as a prisoner, a brother of Abu'l-Fath of Sarmin. At first he was content to levy tribute from the Assassins and leave them in possession, but in September of the same year he returned and blockaded the town into surrender. Abu'l-Fath of Sarmin was captured and put to death by torture; Abu Tahir and his companions were taken prisoner, and allowed to ransom themselves and return to Aleppo.

This first encounter of the Assassins with the Crusaders, and the frustration of their carefully laid plan by a crusading prince, does not seem to have led to any diversion of Assassin attention from Muslim to Christian objectives. Their main struggle was still against the masters, not the enemies of Islam. Their immediate aim was to seize a base, from whatever owners; their larger purpose was to strike at the Seljuq power, wherever it might appear.

In I I 13 they achieved their most ambitious coup to date - the murder in Damascus of Mawdud, the Seljuq emir of Mosul, commander of an eastern expeditionary force that had come to Syria ostensibly to help the Syrian Muslims in their fight against the Crusaders. To the Assassins, such an expedition represented an obvious danger. They were not alone in their fears. In i i i i, when Mawdud and his army reached Aleppo, Ridwan had closed the gates of the city against them, and the Assassins had rallied to his support. Contemporary gossip, as recorded by both Christian and Muslim sources, suggests that the murder of Mawdud was encouraged by the Muslim regent of Damascus.

The danger to the Assassins of eastern Seljuq influence became clear after the death of their patron Ridwan on io December 1113. Assassin activities in Aleppo had made them increasingly unpopular with the townspeople, and in I I I I an unsuccessful attempt on the life of a Persian from the East, a man of wealth and an avowed anti-Ismaili, had led to a popular outburst against them. After Ridwan's death, his son Alp Arslan at first followed his father's policy, and even ceded them a castle on the road to Baghdad. But a reaction soon came. A letter from the Seljuq Great Sultan Muhammad to Alp Arslan warned him against the Ismaili menace and urged him to destroy them. In the city, Ibn Badi', the leader of the townsfolk and commander of the militia, took the initiative, and persuaded the ruler to sanction strong measures. `He arrested Abu Tahir the goldsmith and killed him, and he killed Ismail the da`i, and the brother of the physicianastrologer, and the leaders of this sect in Aleppo. He arrested about zoo of them, and imprisoned some of them and confiscated their property. Some were interceded for, some released, some thrown from the top of the citadel, some killed. Some of them escaped, and scattered throughout the land.'a

Despite this setback, and their failure to secure a permanent castle-stronghold so far, the Persian Ismaili mission had not done too badly during the tenure of office of Abu Tahir. They had made contacts with local sympathizers, winning to the Assassin allegiance Ismailis of other branches and extremist Shiites of the various local Syrian sects. They could count on important local support in the Jabal al-Summaq, the Jazr, and the Banu Ulaym country - that is, in the strategically significant territory between Shayzar and Sarmin. They had formed nuclei of support in other places in Syria, and especially along their line of communication eastwards to Alamut. The Euphrates districts east of Aleppo were known as centres of extremist Shi'ism in both earlier and later periods, and although there is no direct evidence for these years, one may be certain that Abu Tahir did not neglect his opportunities. It is remarkable that as early as the spring of 1114 a force of about a hundred Ismailis from Afamiya, Sarmin and other places was able to seize the Muslim stronghold of Shayzar by a surprise attack, while its lord and his henchmen were away, watching the Easter festivities of the Christians. The attackers were defeated and destroyed by a counter-attack immediately after.

Even in Aleppo, despite the debacle of 1113, the Assassins were able to retain some foothold. In 1119 their enemy Ibn Badi' was expelled from the city, and fled to Mardin; the Assassins were waiting for him at the Euphrates crossing, and killed him together with his two sons. In the following year they demanded a castle from the ruler who, unwilling to cede it and afraid to refuse, resorted to the subterfuge of having it hastily demolished and then pretending to have ordered this just previously. The officer who conducted the demolition was assassinated a few years later. The end of Ismaili influence in Aleppo came in 1124, when the new ruler of the city arrested the local agent of the chief da'i and expelled his followers, who sold their property and departed.

It was a local agent, not the chief da'i himself, who by this time headed the Ismailis in Aleppo. After the execution of Abu Tahir, his successor, Bahram, transferred the main activities of the sect to the South, and was soon playing an active part in the affairs of Damascus. Like his predecessors, Bahram was a Persian, the nephew of al-Asadabadi, who had been executed in Baghdad in I Io1. For a while `he lived in extreme concealment and secrecy, and continually disguised himself, so that he moved from city to city and castle to castle without anyone being aware of his identity'.3 He almost certainly had a hand in the murder of Bursuqi, the governor of Mosul, in the cathedral mosque of that city on 26 November I126. Some at least of the eight assassins who, disguised as ascetics, fell upon him and stabbed him were Syrians. The Aleppine historian Kamal al-Din Ibn al-Adim tells a curious story. `All those who attacked him were killed except for one youth, who came from Kafr Nasih, in the district of Azaz [north of Aleppo] and escaped unhurt. He had an aged mother, and when she heard that Bursuqi was killed and that those who attacked him were killed, knowing that her son was one of them, she rejoiced, and anointed her eyelids with kohl, and was full of joy; then after a few days her son returned unharmed, and she was grieved, and tore her hair and blackened her face.'4

From the same year, 1126, come the first definite reports of co-operation between the Assassins and the Turkish ruler of Damascus, Tughtigin. In January, according to the Damascene chronicler Ibn al-Qalanisi, Ismaili bands from Horns and elsewhere, `noted for courage and gallantry', joined the troops of Tughtigin in an unsuccessful attack on the Crusaders. Towards the end of the year Bahram appeared openly in Damascus, with a letter of recommendation from Il-Ghazi, the new ruler of Aleppo. He was well received in Damascus, and with official protection soon acquired a position of power. His first demand, in accordance with the accepted strategy of the sect, was for a castle; Tughtigin ceded him the fortress of Banyas, on the border with the Latin kingdom of Jerusalem. But that was not all. Even in Damascus itself the Assassins were given a building, variously described as a `palace' and a `mission-house', which served them as headquarters. The Damascus chronicler puts the main blame for those events on the vizier al-Mazdagani, who, though not himself an Ismaili, was a willing accomplice in their plans and the evil influence behind the throne. Tughtigin, according to this view, disapproved of the Assassins, but tolerated them for tactical reasons, until the time came to strike a decisive blow against them. Other historians, while recognizing the role of the vizier, place the blame squarely on the ruler, and ascribe his action in large measure to the influence of Il-Ghazi, with whom Bahram had established friendly relations while still in Aleppo.

In Banyas, Bahram rebuilt and fortified the castle, and embarked on a course of military and propagandist action in the surrounding country. `In all directions,' says Ibn al-Qalanisi, `he dispatched his missionaries, who enticed a great multitude of the ignorant folk of the provinces and foolish peasantry from the villages and the rabble and scum....' 5 From Banyas, Bahram and his followers raided extensively, and may have captured some other places. But they soon came to grief. The Wadi al-Taym, in the region of Hasbayya, was inhabited by a mixed population of Druzes, Nusayris, and other heretics, who seemed to offer a favourable terrain for Assassin expansion. Baraq ibn Jandal, one of the chiefs of the area, was captured and put to death by treachery, and shortly afterwards Bahram and his forces set out to occupy the Wadi. There they encountered vigorous resistance from Dahhak ibn Jandal, the dead man's brother and sworn avenger. In a sharp engagement the Assassins were defeated and Bahram himself was killed.

Bahram was succeeded in the command of Banyas by another Persian, Ismail, who carried on his policies and activities. The vizier al-Mazdagani continued his support. But soon the end came. The death of Tughtigin in 1128 was followed by an antiIsmaili reaction similar to that which had followed the death of Ridwan in Aleppo. Here too the initiative came from the prefect of the city, Mufarrij ibn al-Hasan ibn al-Sufi, a zealous opponent of the sectaries and an enemy of the vizier. Spurred on by the prefect, as well as by the military governor Yusuf ibn Firuz, Buri, the son and heir of Tughtigin, prepared the blow. On Wednesday, 4 September 1129, he struck. The vizier was murdered by his orders at the levee, and his head cut off and publicly exposed. As the news spread, the town militia and the mob turned on the Assassins, killing and pillaging. `By the next morning the quarters and streets of the city were cleared of the Batinites [= Ismailis] and the dogs were yelping and quarrelling over their limbs and corpses.'6 The number of Assassins killed in this outbreak is put at 6,ooo by one chronicler, io,ooo by another and 20,ooo by a third. In Banyas, Ismail, realizing that his position was untenable, surrendered the fortress to the Franks and fled to the Frankish territories. He died at the beginning of I13o. The oft-repeated story of a plot by the vizier and the Assassins to surrender Damascus to the Franks rests on a single not very reliable source, and may be dismissed as an invention of hostile gossip.

Other books

Shame by Salman Rushdie

After Midnight by Colleen Faulkner

Girl on a Slay Ride by Louis Trimble

The Clovel Destroyer by Thorn Bishop Press

Monza (Formula Men #1) by Pamela Ann

The Woods at Barlow Bend by Jodie Cain Smith

A Rogue of My Own by Johanna Lindsey

300 15-Minute Low-Carb Recipes by Dana Carpender

The Darkest Secret: A New Adult Romance Novel by Pine, Jessica

Night Sky (Satan's Sinners MC Book 3) by Kay, Colbie