The Battle of White Sulphur Springs (8 page)

Read The Battle of White Sulphur Springs Online

Authors: Eric J. Wittenberg

Schoonmaker's 14

th

Pennsylvania Cavalry emerged from a dense fog and ran into an enemy picket post near Warm Springs. They captured all of the pickets, but an officer on a fast horse escaped and reported the advance of Averell's

army

. The 14

th

Pennsylvania then charged and surprised a strong enemy force and drove it up the mountain to where Jackson's main force waited. “Our boys fought bravely and many of them sold their lives dearly, but were overpowered by superior numbers and driven from the field,” recalled the regimental historian of the 14

th

Pennsylvania. “Many were killed and wounded on both sides. Under a flag of truce we gathered up our fallen comrades, buried the dead, and cared for the wounded as best we could.”

130

With those minimal casualties, Averell drove Jackson and his cavalry right out of Pocahontas County and away from any opportunity to form a junction with any other Confederate forces that might have been operating in the area.

131

The Fourth Separate Brigade covered another twenty-five miles that day.

132

When the Federals entered Warm Springs, they learned that Mary Custis Lee, the wife of General Robert E. Lee, had left there just a few days earlier, hoping to escape from the coming Yankee horde.

133

Jackson described the rout. “Observing that they were surrounding me, I fell back in time, for ten minutes afterward they surrounded the position I had occupied, and, discovering my retreat, rushed after me,” he reported. “As the country between Jackson's River and Warm Springs Mountain gave their large force of cavalry the advantage, and as I knew there was a route to my left to Warm Springs which they could take and reach there before I could with my train (which was then but a short distance in my front), I fell back to Warm Springs Mountain, and placed my command in position for defense.” Jackson assumed a defensive position there and waited for an hour until the head of Averell's pursuing column appeared in his front. “I soon saw that the effort of the enemy was merely to amuse me in front while he moved a force equal to mine in my rear and also on my right flank,” recounted Jackson. After skirmishing for a few minutes, Jackson withdrew to safety several miles away, effectively out of the fight.

134

A Confederate officer defended Jackson's conduct during Averell's advance. “Colonel Jackson was left alone to delay, as best he could, the progress of the enemy,” recalled Lieutenant Colonel George M. Edgar, who commanded a unit assigned to Jones's department, “and though active, skillful, and persistent in his resistance of the advancing column, was successively flanked by the greatly superior opposing forces, and driven back beyond the Warm Springs, the Federal General's evident purpose being to create the impression that Staunton was the objective point of the expedition.”

135

Lieutenant John R. Meigs had a different take on the rout of Jackson's troopers. “We have by moving down from Petersburg to Franklin & Monterey and Huntersville occasioned a general skedaddle of all detachments in the Western Mts for fear of being cut off,” Lieutenant Meigs told his father.

There are no troops but guerrillas infesting the Alleghanys & W of this place. Our information leads us to believe that all rebel troops intend to go East but that many of the soldiers will desert the army and take up bushwhacking rather leave the section to fight. We will we hope either capture or chase out of the Country all the rebel Force and the whole of W Va would then be in our possession if we choose to hold it

.

136

The already challenging march grew even more arduous. The horses of the Fourth Separate Brigade were in bad shape, desperately needing horseshoe nails and some rest. And the surrounding countryside was buzzing with angry bees. “On our march which we hope will have been sort of a raking movement along the rebel line of outposts passing successfully in their rear we were a complete surprise as far as Monterey,” observed Meigs. “The whole country is now however alarmed and up to bushwhacking.”

137

Bullets buzzed along the column like so many riled-up hornets.

After determining that the prospect of overtaking Jackson was remote, Averell “determined to turn my column toward Lewisburg, hoping that my movement up to the Warm Springs had led the enemy to believe that I was on my way to his depots in the vicinity of Staunton.” His troopers then made a rapid march of twenty-five miles to the important crossroads village of Callaghan in Allegany County, destroying the saltpeter works on the Jackson River as they went.

138

After arriving at Callaghan, Averell sent out reconnoitering parties toward Covington and Sweet Springs, capturing several enemy wagons near Covington and destroying the saltpeter works there.

139

This expedition meant that the Fourth Separate Brigade was now more than one hundred miles from its final destination at Beverly, whereas it had only been about fifty miles from Beverly while resting and awaiting the arrival of supplies at Petersburg. Its lines of communication and supply grew more attenuated with each step taken.

Along the way, Averell's command passed Warm Springs, where the Federals paused to enjoy the contrast of the warm and cold springs that flowed there. “It is a town of fine hotels, with both houses, gardens, shrubbery, arbors, and fine roads leading to it from the east, and but one good road leading west, and that to a resort of the same kind, the White Sulphur,” recounted a member of the 8

th

West Virginia.

140

The Fourth Separate Brigade camped at Callaghan, five miles from Covington, on the night of August 25, finding plenty of chickens, grain and other supplies for the taking. The weary, parched soldiers found a cool spring that produced sufficient volumes of water to fill the needs of the entire brigade but were shocked to find a guard posted at the spring to keep them away from it. “Soldiers, weary, worn and thirsty, must go to the creek and use the water out of which the horses drank,” complained one.

141

“Here we waited until two o'clock in the morning,” recalled an officer of the 8

th

West Virginia.

142

While his weary men and horses rested, Averell reflected on the progress of his raid to date. So far, he had fulfilled every portion of Kelley's orders for the expedition. He had driven Jackson and two other Confederate forces out of Pocahontas County with minimal losses. He had destroyed Camp Northwest and its important supply depot, and he had captured supplies for his own use. He had captured Huntersville and had left a garrison there as ordered. So far, the expedition had gone flawlessly.

However, that was about to change dramatically.

3

The Confederates Respond

As Averell's column wound its way south, the “grapevine telegraph” buzzed with frantic activity, spreading word of the approach of the invading force across the countryside. As early as August 10, word filtered in that “the enemy [is] reported concentrating heavily at Moorefield to attack Staunton via Franklin and McDowell.”

143

On August 18, General Robert E. Lee weighed in. He had correctly divined Averell's intentions and responded by instructing Major General Samuel Jones, commander of the Southwestern Department, to “threaten the enemy's flank, in making any movement through these passes, by a demonstration toward Huntersville, especially any approach via Monterey. I hope you will be successful in beating back any attempt he may make on your lines in the direction of Lewisburg.”

144

By August 23, “grapevine messages began pouring into the District Headquarters, then at Lewisburg, to the effect that Gen. Averell, with a large force of cavalry and artillery, was advancing from the northwest to raid the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad, which was one of the chief arteries for supplying the army of General Lee,” remembered a Virginia artillerist.

145

Those grapevine messagesâpartly based on rumorsâinflated the size of Averell's force to five to ten thousand effectives, the prospect of which sent a shiver up Jones's spine.

146

After hearing these reports, Jones concluded that the New Yorker and his mounted army were on a raid toward Staunton.

147

Preventing Averell from severing the critical supply lifeline was crucial, and the Confederates were determined to pull out the stops to do so. “Celerity was absolutely necessary, for if General Averell should pass White Sulphur, there would be no force to prevent his reaching the railroad and doing immense injury to the line of transportation and communication between Richmond and Tennessee, and the country to the west,” observed an early historian of the battle.

148

Even though the real object of the raid was unknown to the Confederates, they began making preparations to give the Fourth Separate Brigade a warm reception.

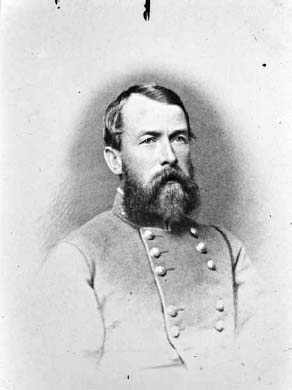

Major General Samuel Jones, commander of the Army of Western Virginiaand Eastern Tennessee.

Library of Congress

.

There was still a large degree of guesswork involved. “To know for sure the road Averell would take and be prepared to meet him on favorable ground was the momentous question with our commanding officer,” noted the same artillerist.

149

Major General Samuel Jones was the commanding officer facing that challenge. Sam Jones commanded the Army of Western Virginia, which consisted of four brigades that operated largely independently. Jones, age forty-four, was a West Pointer. He graduated in 1837 and was an accomplished artillerist. He spent five years as an assistant professor of mathematics and as an assistant instructor in artillery tactics at West Point from 1846 to 1851 and then served as assistant to the judge advocate of the army until he resigned his commission on April 27, 1861, to accept an appointment as major of artillery in the military forces of Virginia. He was promoted to colonel and then was appointed brigadier general and chief of artillery and ordnance for the Army of Northern Virginia on July 22, 1861, the day after the First Battle of Bull Run. He commanded an infantry brigade for a time and then became commander of the Department of Florida. In May 1862, he was promoted to major general, and on September 23, 1862, he was appointed to command the Department of East Tennessee.

150

Jones's geographic area of authority was uncertain. “Its boundaries, from the nature of things, were not clearly defined, but varied with the exigencies of the times,” wrote Jones, referring to himself in the third person. “On September 1 [1863], his command extended from the vicinity of Staunton, in the Valley, to Saltville, in Southwest Virginia, a distance, as the crow flies, of about 200 miles, and by the traveled routes of nearly 300.” Jones had fewer than six thousand total soldiers to defend such a large geographic area, a force “wholly inadequate for the defense of so extensive and important a country, from which a large part of the supplies for General [Robert E.] Lee's army was drawn, and a railroad of nearly 200 miles in length, the only line of transportation from East Tennessee through to eastern Virginia.” The September 1863 returns for the Union Department of West Virginia, by contrast, showed approximately twenty-three thousand men present for duty.

151

“He is about 45 or 50 years of age, I should think, about 5 ft., 10 inches in height, slightly built, light hair & sandy mustache and whiskers,” a captain of the 8

th

Virginia Cavalry described Jones. “His expression is care-worn, and colorless. He is said to have distinguished himself by his bravery at the first battle of Manassas, and as he is a sensible man and understands his business, it is a pity for him that he should have been sent to this great western burial ground of military chieftains.”

152

Jones was about to be tested.

Amiable forty-year-old Brigadier General John Echols normally commanded the First Brigade assigned to Jones's department. Echols, a Harvard-trained lawyer and politician, proved himself to be a competent soldier. He also suffered from serious health problems that plagued him throughout the war and prevented him from reaching his potential. Echols believed that he suffered from heart disease, which explains his frequent disability.

153

Consequently, his poor physical condition often prevented him from active duty and meant that he was seldom in command of his troops.

154

“He was not a field man,” accurately observed Lieutenant Colonel George Edgar, who commanded one of the units in his brigade, “though an efficient organizer.”

155

During the summer of 1863, he was detailed to serve on a three-man court of inquiry convened in Richmond by the Confederate government to determine why the critical Mississippi River bastion of Vicksburg fell to Union forces commanded by Major General Ulysses S. Grant on July 4, 1863. When Echols's disabilities or other duties prevented him from commanding his troops, his brigade's senior colonel, George S. Patton of the 22

nd

Virginia Infantry, ably led it in his place. Patton led the First Brigade so well that it was often called Patton's Brigade and not Echols's brigade.