The Beasts that Hide from Man (16 page)

Read The Beasts that Hide from Man Online

Authors: Karl P.N. Shuker

What makes the Nicaraguan “dog devourer” of particular note is that reports of a similar entity have also emerged further north, where it is referred to as the Mexican snake-tree. Once again, it featured in Wilson’s column, within an item for September 24, 1892:

The “snake-tree” is described in a newspaper paragraph as found on an outlying spur of the Sierra Madre, in Mexico. It has movable branches (by which, I suppose, is meant sensitive branch es), of a “slimy, snaky appearance,” which seized a bird that incautiously alighted on them, the bird being drawn down till the traveller lost sight of it. Where did the bird go to? Latterly it fell to the ground, flattened out, the earth being covered with bones and feathers, the débris, no doubt, of former captures. The adventurous traveller touched one of the branches of the tree. It closed upon his hand with such force as to tear the skin when he wrenched it away. He then fed the tree with chickens, and the tree absorbed their blood by means of the suckers (like those of the octopus) with which its branches were covered.

I confess this is a very “tall” story indeed. A tree which is not only highly sensitive, but has branches which suck the blood out of the birds it captures, is an anomaly in botany. Mexico is surely not quite such an unexplored territory that a tale like this should go unverified. I give the story simply for what it is worth. A lady correspondent, however, reminds me that in Charles Kingsley’s West Indian papers he describes a similar tree to the Nicaraguan plant of Mr. Dunstan.

A number of points can be made in relation to Wilson’s above comments. First, it seems strange that whereas he is highly skeptical of the snake-tree’s alleged capabilities, he seems to have rather less difficulty in accepting these selfsame talents for the Nicaraguan plant. Indeed, judging from the similarities in the descriptions of these two plants, it seems reasonable to assume that they represent closely related species. In reality, Wilson’s doubt concerning the Mexican plant seems to stem not so much from its functional morphology as from its geographical locality. Yet as cryptozoologists will readily point out, even today Mexico can present some notable mysteries for the naturalist. This is best exemplified by the onza. This elusive cheetah-like cat’s existence has been denied by zoologists for more than three centuries, but it has frequently been reported by native Mexicans, and alleged onza skulls and specimens have also been collected. Moreover, the newspaper account referred to by Wilson is not the only source of data regarding a vampiresque Mexican mystery plant.

Despite undertaking a detailed bibliographical search, I have so far been unable to locate that particular newspaper article. However, during my search I did uncover a more recent account, which seems to refer to a comparable species.

In early 1933, the French explorer Baron (sometimes designated as Comte) Byron Khun de Prorok led a party of explorers into the almost impenetrable jungle region of the Chiapas, in southern Mexico, and in the August 1934 issue of

Wide World Magazine

he recounted some of the more memorable episodes that occurred during this journey. The first of these is the one of interest to us, which took place just two hours after first entering the jungle, by which time its omnipresent humidity had begun to take its toll:

After two hours’ march we breathed with difficulty, and were bathed in perspiration.

Suddenly I saw Domingo, the leader of the guides, standing before an enormous plant and making gestures for me to go to him. I wondered what could be the matter.

I soon saw; the plant had just captured a bird! The poor creature had alighted on one of the leaves, which had promptly closed, its thorns penetrating the body of the little victim, which endeavoured vainly to escape, screaming meanwhile in agony and terror.

“Plante vampirel”

explained Domingo, a cruel smile spreading over his face.Involuntarily I shuddered; the forest was casting its evil spell upon me.

It is quite possible that this “vampire plant” and the snake-tree (and perhaps even the Nicaraguan example too?) are the same species, their differences in morphology due not to nature but to inaccurate reporting. De Prorok was a renowned explorer, hence it is probably best to look upon his description as being more accurate than the earlier newspaper account. Certainly, it would be easier to accept the existence of a plant with sensitive thorn-bearing leaves functioning somewhat like those of the Venus flytrap than the evolution of botanical devices bearing suckers capable of actively draining a bird of its blood.

Unlike animals, plants do not possess a nervous system. However, they do generate electrical signals that greatly resemble nerve impulses. Recordings of electrical signals (action potentials) generated by the Venus flytrap were first obtained as long ago as 1873, by London physiologist Sir John Burdon-Sanderson—when he bent one of the trigger-hairs on one of this carnivorous plant’s leaves, he recorded the passage across that leaf of an electrical signal traveling at 20 mm per second. It has since been shown that if two such signals are generated (i.e. by something brushing against one or more of the leaf’s trigger hairs) within 20 seconds, these stimulate the leaf’s closure (it folds along its midrib, like a book closing), effecting the flytrap. This is an extremely rapid movement (for a plant), taking only a second or so; the movement itself is engineered via extremely rapid growth of the leaf, triggered by a fall in the pH of the leaf’s cell walls (i.e. by an increase in their acidity).

In the famous “sensitive plant”

Mimosa pudica

, electrical impulses are propagated throughout any leaf that is touched or brushed against. These impulses cause each of the leaflets comprising that leaf to fold up—another notable rapid movement taking no more than a second, but this time created by turgidity changes in specialized regions of the leaf called pulvini (absent in Venus flytraps).

A mechanism involving the touch-induced generation of electrical impulses stimulating the rapid closure of thorn-bearing leaves is indicated by de Prorok’s description of the Mexican “vampire tree,” and is certainly well within the capability of plant evolution.

These deadly entities may also be akin to a second carnivorous mystery plant from Brazil that was noted by Harold T. Wilkins in

Secret Cities of Old South America

(1952). Like his earlier-mentioned octopod (devil) tree, Wilkins’s second species is supposedly equipped with motile tentacular branches. Unlike the octopod tree, however, this species’ whereabouts can be readily detected by humans because it releases a smell resembling the stink of a rotting carcass. Its preferred prey consists of small birds, which it lures with sweet-tasting berries. When an unsuspecting bird alights upon it to peck at its berries, one of the tree’s tentacles seizes one of its wings immediately, and unless the bird can tear itself away it is pulled up against the tree’s trunk, held in place by suckers, and crushed to death—after which its blood is absorbed by the suckers before its dry, lifeless carcass is dropped to the ground.

Also reported from Brazil, and even more formidable, is the monkey-trap tree. In his book

Carnivorous Plants

(1974), Randall Schwartz refers to a “recent report” (but without providing any reference for this) credited to a Brazilian explorer called Mariano da Silva. According to Schwartz’s rendition of this report, da Silva had been searching for the settlement of Yatapu Indians on the Brazilian border with Guyana when he encountered an animal-devouring tree. It releases a very distinctive scent that is particularly attractive to monkeys, luring them to it and enticing them to climb its trunk—whereupon its leaves totally envelop them, rendering these hapless creatures invisible and inaudible to anyone witnessing this grisly spectacle. Three days or so later, the leaves open again, and from them drop the bones of their victims, from which every vestige of flesh has been stripped.

If genuine, the mechanism involved once again compares to that of the Venus flytrap, but the leaves must be much tougher and extraordinarily inflexible to be capable of suppressing the struggles of creatures as large as monkeys.

Rather more plausible than a monkey-ingesting tree is a plant capable of consuming mice. After all, as noted by Hal Bowser, some pitcher plants are so large that they can not only trap insects and spiders but even tiny mammals and small snakes, too. However, there may well be some mouse eaters still eluding official discovery and description—as in the case of the cryptic rodent remover supposedly exhibited for a while in London. As an example of other carnivorous plants to substantiate his detailed account of Madagascar’s man-eating tree, Chase Salmon Osborn included the following account in his book

Madagascar, Land of the Man-Eating Tree

(1924):

At the London Horticultural Hall in England there is a plant that eats large insects and mice. Its principal prey are the latter. The mouse is attracted to it by a pungent odor that emanates from the blossom which encloses a perfect hole just big enough for the mouse to crawl into. After the mouse is in the trap bristle-like antennae infold it. Its struggles appear to render the Gorgonish things more active. Soon the mouse is dead. Then digestive fluids much like those of animal stomachs exude and the mouse is macerated, liquefied and appropriated. This extraordinary carnivorous plant is a native of tropical India. It has not been classified as belonging to any known botanical species.

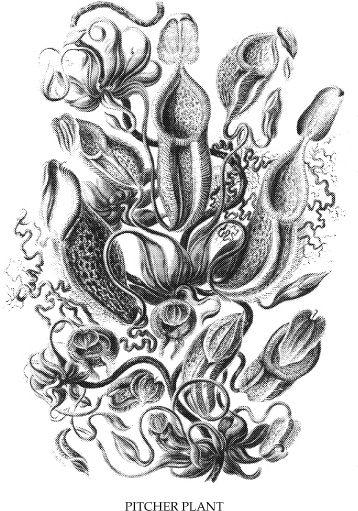

Of all the mystery carnivorous plants documented here, this seems to be the most feasible one. Its mode of operation recalls that of the familiar pitcher plants. These species possess a tall vertical pitcher-shaped receptacle into which tiny animals are lured by sweet nectar secretions on the outside of the pitcher, but once inside they are unable to crawl out again, due to the pitcher’s slippery internal wall and inward-curving spines at its brim, and so they fall down to the bottom, into a pool of fluid containing digestive enzymes, where they swiftly drown and become digested. In the case of the mouse-eating plant, a noteworthy modification has been added to this mechanism, whereby the trap’s internal wall bears retaining spines that are reminiscent of the external but functionally comparable tentacles of another group of carnivorous plants, the sundews.

An inordinately deceitful plant of prey is a monstrous man-eater that became known to a Captain Arkright, an explorer, in 1581. According to South Pacific folklore, it existed on one of a group of islets encircled by a coral ring in this region of the world. The islet in question was called El Banoor (“Island of Death”) on account of its sinister inhabitant. The plant was huge, with enormous, brightly hued petals that opened out to yield a seductive, scented chamber whose soothing colors and bewitching fragrance beguiled many an unsuspecting human, tempting him to enter and rest upon its lowermost petals, and thence to close his eyes and sleep—a sleep from which he would never awaken. For as he slumbered, the plant’s petals would envelop him and bathe his unresisting form in fiery acidic juices, digesting his body even as its narcotic fragrance retained its all-embracing shroud around his mind.

In his book

Myths and Legends of Flowers, Trees, Fruits, and Plants

(1911), Charles M. Skinner dismisses this report as nothing more than a greatly exaggerated early account of a Venus flytrap! However, this unmistakable species is wholly confined in the native state to a single large bog around Wilmington, North Carolina (a bog which, intriguingly, just happens to reside in what is thought by some to be an ancient meteorite crater!).

Conversely, Dr. Roy P. Mackal wondered whether it could have been a distorted account of

Rafflesia arnoldii

from Sumatra, a parasitic species that sends root-like structures resembling the mycelia of fungi into the roots of another plant, a vine called

Tetrastigma

, in order to draw up nourishment. What makes

R. arnoldii

so famous in biological circles is its flower—huge, flat, and at least three feet across, constituting the largest flower in the world. It is composed of several crimson petals, leathery in texture and speckled with cream blotches, plus a central bowl containing spike-like structures and several pints of dirty water.

However, because this flower is horizontal, not vertical, it does not correspond with the South Pacific death flower’s structure as described to Arkright. It seems that although

Rafflesia

could be stepped

upon

, it could not be stepped

into

.