The Beasts that Hide from Man (11 page)

Read The Beasts that Hide from Man Online

Authors: Karl P.N. Shuker

A BRAZILIAN MYSTERY CAT—FICTION OR FACT?

Several years ago, I read a short story by Conan Doyle called “The Brazilian Cat,” published in 1922, which featured a huge, ferocious, ebony-furred felid that had been captured at the headwaters of the Rio Negro in Brazil. According to the story: “Some people call it a black puma, but really it is not a puma at all.” Yet there was no mention of cryptic rosettes, which a melanistic (all-black) jaguar ought to possess, and it was almost 11 feet in total length, thereby eliminating both puma and jaguar from consideration anyway. Hence I simply assumed that Doyle’s feline enigma was fictitious, invented exclusively for his story. But following some later cryptozoological investigations of mine, I am no longer quite so sure.

To begin with: in

Exploration Fawcett

(1953), the famous lost explorer Lt.-Col. Percy Fawcett briefly referred to a savage “black panther” inhabiting the borderland between Brazil and Bolivia that terrified the local Indians, and it is known that Fawcett and Conan Doyle met one another in London. So perhaps Fawcett spoke about this “black panther” and inspired Doyle to write his story. But even so, it still does not unveil the identity of Fawcett’s panther. Black pumas are notoriously rare—only a handful of specimens have been obtained from South and Central America (and none ever confirmed from North America). Conversely, black jaguars are much more common, and with their cryptic rosettes they are certainly reminiscent of (albeit less streamlined than) genuine black panthers, i.e. melanistic leopards. However, the mystery of Brazil’s black panthers is far more abstruse than this.

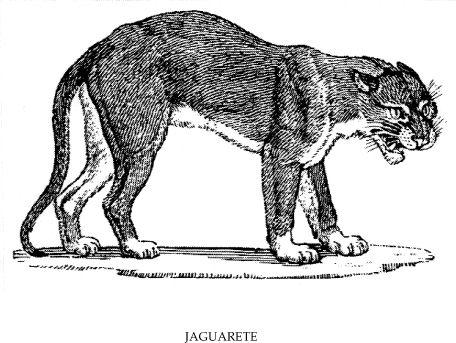

As long ago as 1648, traveler Georg Marcgrave mentioned a shiny Brazilian black cat, variegated with black spots, which he dubbed the jaguarete. This felid, clearly resembling a typical melanistic jaguar, was later documented from Guyana, too, and was referred to as the black tiger—a name popularly applied in Latin America to black jaguars. So far, so good.

However, when the famous British naturalist Thomas Pennant described and depicted this “black tiger” in 1771, he portrayed it with plain black upperparts and whitish or ashen underparts— whereas true black jaguars are uniformly black all over. Yet black pumas do indeed have paler underparts, and Pennant’s French contemporary, Buffon, actually referred to the jaguarete as the

cougar noire

(“black cougar”), indicating a puma identity for it.

The jaguarete was even given its own scientific name,

Felis discolor

, by German naturalist Johann Christian Daniel Schreber, in 1775. Yet as it seemed to be nothing more than a non-existent composite creature—”created” by early European naturalists unfortunately confusing reports of black jaguars with black pumas—the jaguarete eventually vanished from the wildlife books. Even so, its rejection by zoologists as a valid, distinct felid may be somewhat premature. This is because some reports claimed that the jaguarete was much larger than either the jaguar or the puma—a claim lending weight to the prospect that a third, far more mysterious black cat may also have played a part in this much-muddled felid’s history.

YAN A PUMA—

AN ALL-BLACK ANOMALY FROM PERU

Dr. Peter J. Hocking is a zoologist based at the Natural History Museum of the National Higher University of San Marcos, in Lima, Peru. Aside from his official work, for several years he has been collecting and investigating local Indian reports describing various different types of mysterious, unidentified cat said to inhabit the Peruvian cloudforests. One of these, of great relevance here, has been dubbed by him “the giant black panther.”

In an article published by the journal

Cryptozoology

in 1992, Dr. Hocking revealed that this particular Peruvian mystery cat is said to be entirely black, lacking any form of cryptic markings, has large green eyes, and is at least twice as big as the jaguar. Moreover, the Quechua Indians term it the

y ana puma

(“black mountain lion”). This account immediately recalls Conan Doyle’s story of the immense Brazilian black cat. The

yana puma

is apparently confined to montane forest ranges only rarely visited by humans, at altitudes of around 1,600 to 5,000 feet. If met during the day, when resting, it is generally passive, but at night this mighty cat becomes an active, determined hunter that will track humans to their camps and has sometimes slaughtered an entire party while they slept, by lethally biting their heads.

When discussing the

yana puma

with mammalogists, Hocking has frequently been informed that it is probably nothing more than a large melanistic jaguar. Yet as he pointed out in his article, such animals do not attain the size claimed for this mysterious felid (nor do melanistic pumas)—and the Indians are adamant that it really is quite enormous. Nevertheless, the

yana puma

could still merely be a product of native exaggeration, inspired by real black jaguars (or pumas) but distorted by superstition and fear.

However, a uniformly black, unpatterned felid does not match either a black jaguar or a black puma—yet it does compare well with Conan Doyle’s Brazilian cat. Moreover, as some jaguarete accounts spoke of a black cat that was notably larger than normal jaguars and pumas, perhaps the

yana puma

is not limited to Peru, but also occurs in Brazil. Is it conceivable, therefore, that Doyle (via Fawcett or some other explorer contact) had learned of the

yana puma

and had based his story upon it? If so, it would be one of the few cases on file in which a bona fide mystery beast had entered the annals of modern-day fiction before it had even become known to the cryptozoological — let alone the zoological—community!

For something is amiss or out of place When mice with wings can wear a human face

.T

HEODORE

R

OETHKE

—“T

HE

B

AT

”

FROM THE EARLIEST TIMES, BATS HAVE BEEN VIEWED AS creatures of mystery—as arcane and abstruse as the opaque shadows of Night that animate so many of their kind. It is certainly true that during the past two centuries science has succeeded in brushing aside many cobwebs of longstanding confusion and credulity enveloping these winged wanderers, but there are a host of others still to be dealt with. Indeed, as disclosed in this chapter, there are certain sources of provocative (and scientifically inconvenient?) but little-known data on file that not only question the validity of some fondly treasured tenets of traditional bat biology, but also provide startling evidence for the existence of several dramatic species of bat still awaiting formal zoological discovery.

AHOOL

AND THE

OLITIAU—

OR, HOW BIG IS A BAT?

One evening in 1927, at around 11:30 p.m., naturalist Dr. Ernst Bartels was in bed inside his thatched house close to the Tjidjenkol River in western Java, and lay listening to the surrounding forest’s clamorous orchestra of nocturnal insects. Suddenly, a very different sound came winging to his ears from directly overhead—a loud, clear, melodious cry that seemed to utter “A-hool!” A few moments later, but now from many yards further on, the cry came again—a single “A-hool!” Bartels snatched his torch up and ran out, in the direction of this distinctive sound. Less than 20 seconds later he heard it once more, for the third and last time—a final “A-hool!” that floated back towards him from a considerable distance downstream. As he recalled many years later in a detailed account of this and similar events

(Fate

, July 1966), he was literally transfixed by what he had heard—not because he

didn’t

know what it was, but rather because he

did!

The son of an eminent zoologist, Dr. Bartels had spent much of his childhood in western Java, and counted many of the local Sundanese people there as his close friends. Accordingly, he was privy to many strange legends and secret beliefs that were rarely voiced in the presence of other Westerners. Among these was the ardent native conviction that this region of the island harbored an enormous form of bat. Some of Bartels’s Sundanese friends claimed to have spied it on rare occasions, and the descriptions that they gave were impressively consistent. Moreover, as he was later to discover, they also tallied with those given by various Westerners who had reputedly encountered this mysterious beast.

It was said to be the size of a one-year-old child; with gigantic wings spanning 11 to 12 feet; short, dark-grey fur; flattened forearms supporting its wings; large, black eyes; and a monkey-like head, with a flattish, man-like face. It was sometimes seen squatting on the forest floor, at which times its wings were closed, pressed up against its flanks; and, of particular interest, its feet appeared to point backwards. When Bartels questioned eyewitnesses as to its lifestyle and feeding preferences, he learned that it was nocturnal, spending the days concealed in caves located behind or beneath waterfalls, but at night it would skim across rivers in search of large fishes upon which it fed, scooping them from underneath stones on the beds of the rivers. At one time, Bartels had suggested that perhaps the creature was not a bat but some type of bird, possibly a very large owl, but these opinions were greeted with great indignation and passionate denials by his friends, who assured him in no uncertain terms that they were well able to distinguish a bat from a bird! And as some were very experienced, famous hunters, he had little doubt concerning their claims on this score.

Even so, the notion of a child-sized bat with a 12-foot wingspan seemed so outrageous that he still had great difficulty in convincing himself that there might be something more to it than native mythology and imagination—until, that is, the fateful evening arrived when he heard that unforgettable, thrice-emitted cry, because one of the features concerning the giant bat that all of his friends had stressed was that when flying over rivers in search of fish this winged mystery beast sometimes gives voice to a penetrating, unmistakable cry, one that can be best rendered as “A-hool! A-hool! A-hool!”

Indeed, the creature itself is referred to by the natives as the

ahool

, on account of its readily recognizable call—totally unlike that of any other form of animal in Java, as Bartels himself was well aware.

Transformed thereafter from an

ahool

skeptic to a first-hand

ahool

“earwitness,” Bartels set about collecting details of other

ahool

encounters for documentation, and eventually news of his endeavors reached veteran cryptozoologist Ivan T. Sanderson, who became co-author of Bartels’s above-cited

Fate

article.

The

ahool

was of special interest to Sanderson, because he too had met with such a creature—but not in Java. Instead, he had been in the company of fellow naturalist Gerald Russell in the Assumbo Mountains of Cameroon, in western Africa, collecting zoological specimens during the Percy Sladen Expedition of 1932. As Sanderson recorded in his book

Animal Treasure

(1937), he and Russell had been wading down a river one evening in search of tortoises to add to their collection when, without any warning, a jet-black creature with gigantic wings and a flattened, monkey-like face flew directly toward him, its lower jaw hanging down and revealing itself to be unnervingly well-stocked with very large white teeth. Sanderson hastily ducked down into the water as this terrifying apparition skimmed overhead, then he and Russell fired several shots at it as it soared back into view, but the creature apparently escaped unscathed, wheeling swiftly out of range as its huge wings cut through the still air with a loud hissing sound. Within a few moments, their menacing visitor had been engulfed by the all-encompassing shadows of the night, and did not return.

After comparing notes, Sanderson and Russell discovered that they had both estimated the creature’s wingspan to be at least 12 feet (matching that of the

ahool)

. When they informed the local hunters back at their camp of their experience, the hunters were petrified with fear—staying only as long as it took them to shriek

“olitiaul”

before dashing away en masse in the direction furthest from the scene of the two naturalists’ encounter! As Dr. Bernard Heuvelmans commented in his own coverage of this incident, within his book

Les Derniers Dragons d’Afrique

(1978),

“olitiau”

may refer to devils and demons in general rather than specifically to the beast spied by Sanderson and Russell, but as these etymological issues have yet to be fully resolved it currently serves as this unidentified creature’s vernacular name.