The Beasts that Hide from Man (8 page)

Read The Beasts that Hide from Man Online

Authors: Karl P.N. Shuker

Morphologically, an ajolote would provide a very plausible explanation for the “legged death worm” of Chongor Gobi. Or at least it would if we are willing to assume that, because amphisbaenids’ heads and tails are very similar in appearance—and because he had only ever seen dead specimens of his “salami” mystery beast—the shepherd may have mistakenly thought that his mystery beast’s “wings” (i.e. its spade-shaped legs) were at its body’s rear end instead of its front end. Even so, as ajolotes constitute an exclusively New World taxonomie family, this identification is zoogeographically unsatisfactory.

Of course, it is conceivable that an Old World amphisbaenid lineage could have given rise to an ajolote counterpart by convergent evolution, but aside from the account of the Chongor Gobi mystery beast (and also Boldoos’s all-too-briefly spied beast?), there is not a scrap of evidence to suggest this. Alternatively, the latter creature could be a species of two-legged lizard—of which a number of species are already known to science.

Yet regardless of its morphological similarity or otherwise to species already known to science, it is still unclear whether or not this legged mystery beast from the Chongor Gobi is indeed one and the same as the seemingly limbless death worm reported elsewhere in the Gobi. Bearing in mind, however, that nomads prefer to keep as great a distance as feasible between themselves and any death worm that they encounter, it is not impossible that the

allghoi khorkhoi

really does possess a small, inconspicuous pair of limbs—but which can only be discerned if viewed at extremely close range or in dead specimens, and whose presence is therefore not widely realized, even among the nomads.

Several taxonomie families of true lizards, i.e. lacertilians (saurians), contain legless species. The most famous are various limbless anguids (including the slow worm

Anguis fragilis

and the European scheltopusik

Ophisaurus apodus)

, and the Australasian snake-lizards or pygopodids (they lack front limbs, and their hind limbs are reduced to scarcely visible scaly flaps). Even so, these bear little resemblance to the death worm, as they have well-differentiated heads with large, wide, readily perceived eyes and long, pointed tails.

Much more vermiform are certain tiny-eyed legless skinks, such as the small, burrowing

Acontias

skinks indigenous to sandy terrain in South Africa and Madagascar, and the larger, forest-dwelling

Feylinia cussori

from tropical Africa. There are also some skinks with hind limbs but without front limbs, such as Australia’s

Lerista bipes

and L.

labialis

. Two small families of limbless worm-like lizards are the blind lizards (dibamids) of Mexico, southeastern Asia, and New Guinea, whose females are legless, but whose males possess a pair of vestigial hind legs in the form of flipper-like stumps; and the anniellids, comprising two species of tiny, shiny-bodied species native to California and Mexico’s Baja California.

Evidently, limblessness and semi-limblessness are not uncommon phenomena among lizards, having evolved independently on several occasions within this reptilian sub-order. Having said that, all of the points raised for and against the death worm being an amphisbaenid also apply in relation to its candidature as a legless lizard—except, that is, for its worm-like mode of locomotion. For whereas this is indeed compatible with an amphisbaenid identity, legless lizards move via horizontal undulations, like snakes.

All known amphisbaenids are non-venomous, but there are two species of venomous lizard—the Gila monster

Heloderma suspectum

from the deserts of the southern U.S. and northwestern Mexico, and the beaded lizard

H. horridum

of Mexico and Guatemala. Both species, however, have two pairs of well-formed limbs, and release their venom only when biting their prey, not by spraying or squirting it like the death worm.

One very curious facet of the death worm’s reported behavior is its propensity for emerging onto the surface of the sand only during the Gobi year’s two hottest months, June and July. It is well known that as reptiles are Poikilothermie (“cold-blooded”), their body temperature varies with that of their surroundings. Accordingly, in temperate climates reptiles sunbathe during sunny days to attain an optimal body temperature for energetic activity, and enter a period of hibernation or inactivity during cold conditions.

Faced with intense heat, however, many reptiles tend to seek shelter in cooler, shady locations (including burrows) during the daytime—especially during the summer months—in order to avoid over-heating and eventual death. Such reptiles as these, which include most desert-dwelling lizards, are known as thermal regulators, actively regulating their body temperature by way of their behavioral activity. The obverse side of this physiological coin is represented among desert reptiles by the thermal conformers, whose preferred habitat acts as a buffer against environmental temperature extremes, so that they rarely need to move from one locality to another for temperature-related reasons.

Prime examples from this latter category of reptiles are desert-dwelling amphisbaenids and legless lizards, which generally remain underground, their body temperature maintained at the same temperature as that of the surrounding sand. Consequently, if the death worm is indeed a f ossorial reptile belonging either to the lizard or to the amphisbaenid sub-order, there does not seem to be any obvious thermal reason why it should emerge onto the surface during the hot summer months. On the contrary, if it were to emerge at all, I would have expected it to have done so during the colder months of the year—when remaining permanently beneath the surface may not have yielded sufficient warmth in order for it to maintain its body at its optimal functioning temperature.

Just like the amphisbaenids and lizards, there are a number of specialized desert-dwelling snakes that are sufficiently vermiform to conjure up favorable comparisons with the traditional death worm description. One taxonomie family that readily comes to mind, for example, comprises the blind snakes (e.g.

Typhlops

spp.). These are small, cylindrical serpents with glossy brown scales, scale-covered eyes, and a spine-tipped tail. Some do inhabit arid, sandy regions, and are rarely seen above the surface. There are species in much of Africa, southern Asia, Australasia, Central America, and the upper half of South America. Another family of worm-like burrowing species are the thread snakes, distributed throughout Africa, most of Central and South America, and parts of western Asia. They have tiny eyes and mouth, a blunt snout and tail, and can be easily mistaken for large earthworms. Like the blind snakes, however, they are inoffensive and non-poisonous.

When I spoke about the death worm to Mark O’Shea, one of Britain’s leading field herpetologists and snake-handlers, he opined that it could be a species of

Ery x

sand boa. Native to arid zones in western Asia, Africa, and southeastern Europe, these burrowing, thick-set snakes with cylindrical bodies, blunt heads, and similarly blunt tails certainly recall the death worm in superficial morphology, and spend much of their time partially or entirely buried in the sand, lying in wait for unsuspecting lizards and rodents to approach near enough to be seized. Unlike the death worm, however, sand boas rarely come out onto the surface of the sand during the day, and they possess distinct eyes.

In addition, the death worm can be readily spied due to its striking dark red color—could this be deliberate warning coloration, signaling the worm’s lethal prowess to would-be attackers? Conversely, sand boas display cryptic coloration, for camouflage purposes, preventing them from being detected by their prey when lurking in the sand.

Moreover, these snakes rarely exceed three feet in length, and are non-poisonous. Mark suggested that the death worm’s alleged ability to squirt venom may well be folklore, which is undeniably a possibility, as noted for all of the previous taxa of animals considered here as putative identities for the death worm. In contrast, the morphological and behavioral differences between the death worm and the sand boas cannot be so readily discounted.

A very different type of desert snake that is indeed dark red sometimes is South Africa’s horned adder

Bitis caudalis

—just one of several sand-inhabiting members of the viper family recorded from the world’s deserts. Unlike sand boas, these species are venomous (though they release their venom when biting their prey, not by squirting it into the air), and live on or just below the surface of the sand, rather than indulging in a predominantly subterranean lifestyle. Unfortunately for those attempting to reconcile such species with the death worm, however, these snakes tend to possess readily visible, heavily keeled scales, large eyes, and the ability to flatten themselves by spreading their ribs, so that they may vanish rapidly beneath the surface of the sand when detecting the approach of a potential prey victim. No such behavior, conversely, has apparently been documented for the death worm.

Nevertheless, there remains one excellent contender among the serpent sub-order for the veiled identity of the death worm. This contender was first brought to my attention when discussing the death worm with Prof. John L. Cloudsley-Thompson—a world-renowned expert on the biology of deserts and editor of the

Journal

of Arid Environments

.

In a letter to me from October 1996, Prof. Cloudsley-Thompson offered the following pertinent thoughts regarding the death worm:

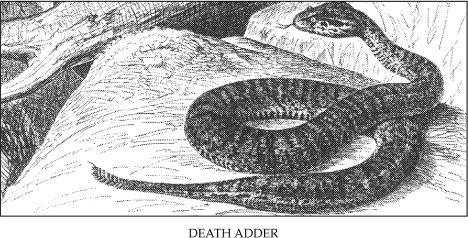

I would have thought that the animal must be a snake…1 do not think that any of the vipers spray poison as cobras do but, like the puff adder, they can reach a large size. One idea that occurs to me is that the Australian ‘death adder’

[Acanthophis antarcticus]

is really an elapid snake which has evolved to occupy a viperine ecological niche. Could the ‘death worm’ be an unknown species that has done the same? The king cobra is not only one of the largest of venomous snakes but, also, one of the most deadly…Many poisonous snakes will spray drops of venom for a short distance, and three species of cobras—the ringhals, black-necked, and (some) Indian—have developed the technique of aiming at the eyes of an aggressor [these are the famous spitting cobras]. The twin jets, according to Bellairs, can be sprayed >2 m [six feet]. Cobra venom is rapidly absorbed from the eye (and perhaps by delicate skin?) but not the venom of vipers. This again might suggest a snake like

Acanthophis

spp. spraying an extremely toxic and rapidly acting venom….Death adders have broad heads,

narrow

necks, stout bodies and thin

rat-like tails

ending in a curved soft spine (? = pointed at both ends)-unlike other snakes. They are extremely toxic. They occur in Australia, New Guinea and islands west as far as Ceram (=Seram), according to Harold Cogger. As they occur in the East Indies, could not a species also be found in East Asia too?…Clearly, it is a matter of weighing one thing against another, but my guess would be a new species or genus of death adder. If this idea is of use I would be very happy to make a present of it to you, to acknowledge or not—as would be best for your publication. No doubt the animal’s food would be chiefly small rodents and, perhaps, other reptiles. It is not clear why some snakes (e.g. true coral snakes) are so much more venomous than would appear necessary.

Prof. Cloudsley-Thompson’s idea that the death worm may in reality be a hitherto-unknown species of death adder is quite fascinating, and is the first identity that offers a factual explanation for the nomads’ reports of this cryptid’s venom-spraying talent.

The elapids are a taxonomie family of snakes housing such familiar if fatal species as the cobras, mambas, kraits, and also the death adder. As outlined above, this unusual snake has acquired via convergent (parallel) evolution a remarkably viper-like (i.e. adderlike) appearance, thus occupying the ecological niche left vacant in Australia by the true vipers—as there is no viper species native to this vast island continent. In other words, the death adder is an elapid impersonating a viper. But what would happen if a death adder also evolved the venom-spitting ability exhibited by certain of its fellow elapids, i.e. the spitting cobras?

As indicated by Cloudsley-Thompson, the result could be a specialized snake able to spray deadly fast-acting, skin-absorbing venom at any would-be attacker from a not inconsiderable distance—thereby corresponding with the descriptions given by the Gobi nomads in relation to the death worm, even including those ostensibly bizarre claims that the worm can kill from a distance, without making direct contact with its victim. In addition, if absorbed through the eyes, the venom could work its lethal effect without needing to be corrosive—although the nomads’ testimony certainly suggests that the venom is acidic.