The Beasts that Hide from Man (29 page)

Read The Beasts that Hide from Man Online

Authors: Karl P.N. Shuker

Similarly, a number of naturalists and other skilled eyewitnesses have reported seeing in the Sunderbans area of eastern India a strain of tiger whose stripes are barely visible against their brownish-red coats, so that they appear stripeless. Once again, such eyecatching specimens as these might well be sufficient to engender the legendary celestial Red Tiger.

As for white tigers: the modern-day strain commonly seen in zoos and wildlife parks is largely if not entirely descended from a magnificent male white tiger called Mohan, captured alive in Rewa on May 27, 1951, and later housed within the summer palace of the Maharajah. However, white tigers have been reported elsewhere in India too, as well as in China, Korea, and Nepal, and the earliest known record of white tigers dates back to 1561, when two of the cubs of a tigress killed by the Mogul emperor Akbar were reported to be white. Consequently, the occurrence of white tigers in Eastern mythology is hardly unexpected.

What may well be unexpected, conversely, is the prospect that even the most dreamlike of the four celestial tigers, the Blue Tiger, could well have a living counterpart. For countless years, there have been reports of blue tigers inhabiting Korea, and particularly Fujian Province in southeastern China, occasionally spied by local people but never captured or shot. In September 1910, however, their reputation for elusiveness suffered a serious blow, when one of these ethereal beasts was almost bagged by a keen American game hunter.

Harry R. Caldwell, who was also a Methodist missionary, was hunting in Fujian when one of his native helpers suddenly directed his attention toward something moving in the undergrowth nearby. Caldwell thought at first that it was another native, dressed in the familiar blue garment worn by many in that region, but when he peered more closely he realized to his great surprise that he was actually looking at the chest and belly of a tiger—a very large tiger whose black-striped fur was not orange-brown, as in normal specimens, but was instead a very distinctive shade of blue.

Caldwell decided to shoot this extraordinary creature, to prove once and for all that such cats really did exist, but the tiger was watching two children gathering vegetation in a nearby ravine, and he knew that if he tried to shoot it from his present position he might injure or otherwise endanger the children too. Consequently, he moved a short distance away, in order to alter the direction of his planned shot, but while he was doing this, the tiger disappeared into the forest, and was not seen by him again.

Although a blue tiger seems impossible, in fact it is quite easily explained. Such tigers almost certainly possess the genes responsible for the smoky blue-mauve coloration characterizing the Maltese breed of domestic cat; in America, fur traders have occasionally obtained comparably hued specimens of the lynx and the bobcat.

According to traditional European mythology, if a cockerel lays a leathery shell-less egg that is hatched in a dung-heap at midnight by a toad, the resulting offspring will be a cockatrice—a monstrous crowing beast combining a scaly reptilian body with the feathered neck, legs, sharp beak, and coxcombed head of a cockerel.

Although it may all seem highly unlikely, the cockatrice’s history does have a basis in fact, due to a bizarre fluke of nature whereby a hen will sometimes undergo a sex change. Through the ages, many such cases have been recorded (more than is widely realized, in fact), in which a seemingly normal hen abruptly begins to transform partially into a cockerel, growing male plumage and a coxcomb, and crowing each day, but often continuing to lay eggs.

In bygone, superstitious days, such a bizarre occurrence would have been seen as an omen of impending doom, leading in turn to the development of the cockatrice legend. In reality, however, the occurrence of one of these “father hens” can be sometimes due to an internal tumor that stimulates the hen to develop male hormones and thence acquire secondary sexual characteristics associated with cockerels. Alternatively, the hen may actually be a hermaphrodite—a freak specimen born with both female and male organs, in which the former dominate for the earlier part of its life but are later subordinated by the latter.

One well-publicized recent “father hen” is Henrietta, featured in a

Daily Mail

report on March 4,1998, who is (or was) one of several hens on Violet Smith’s farm at Aylmerton, near Cromer, Norfolk. For ten years, Henrietta was a totally normal hen—until 1997, that is, when she began growing the green downward-pointing tail feathers, the shiny russet neck plumage, and the large red coxcomb of a typical cockerel. By Christmas 1997, much to the consternation of the farmyard’s real cockerel, she had taken charge of the other, normal hens, and during the last week of February 1998 she gave voice to her first cock-crow. Not surprisingly, she was duly renamed Henry, and has since stopped laying eggs, but experts believe that she may well begin again, just like other father hens often do—but if so, it may be advisable to keep these eggs away from toads and dung-heaps, just in case!

The history of fabulous animals is as complex as many of the animals themselves—deftly but intricately interweaving the morphology and behavior of real creatures with the ever-inquisitive observations of these beasts by our far-distant ancestors, and their attempts to make sense of all that they encountered in the natural world. Yet although fuelled by the limitless powers and talent of the human imagination, in those bygone ages their attempts lacked the moderating control of scientific logic. Consequently, it should really come as no surprise to find that the outcome was a veritable menagerie of monsters—which were too fantastic ever to have lived, but which have also proved too amazing simply to be forgotten. And so these fabulous beasts have survived, animated not by nature but by the human mind, until their true origins have become obscured to all but their most tenacious researchers.

There is a wolf in me…fangs pointed for tearing gashes…a red tongue for raw meat… and the hot lapping of blood — I keep this wolf because the wilderness gave it to me and the wilderness will not let it go

.C

ARL

S

ANDBURG

—

W

ILDERNESS

ALL TOO OFTEN OVERSHADOWED BY THEIR MORE famous feline counterparts, canine mystery beasts are no less intriguing, or diverse, as the following selection of cases readily reveals. Whether they all involve genuine canids, conversely, is another matter entirely!

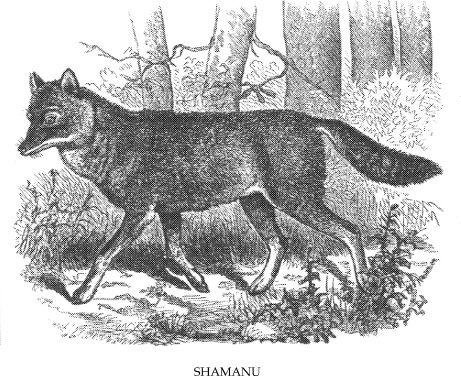

It is, perhaps, only fitting that Japan, famous for its miniature bonsai trees, should also lay claim to the world’s smallest subspecies of wolf. Known as the shamanu or Japanese dwarf wolf

Canis lupus hodophilax

, and sporting a short, dense coat of predominantly ash-grey fur, it measured no more than 45 inches long, including its one-foot tail, and stood a diminutive 14 inches at the shoulder. This was due in particular to its disproportionately short legs, which morphologically alienated the shamanu so dramatically from all other wolves that some zoologists classified it as a wholly distinct species of canid in its own right.

In addition to the shamanu, Japan was once home to a “normal” type of wolf too, known colloquially as the

yezo-okhami

and scientifically as

Canis lupus hattai

. However, this much larger subspecies was extinct by 1887, and had been restricted to Hokkaido. In contrast, the vertically challenged shamanu, colloquially termed the

nihon-okhami

, was not only present on Hokkaido, but also thrived on Honshu, as well as the Kurile Islands.

Japan’s aboriginal people, the Ainu, had referred to the shamanu as the howling god, but its deified status was not enough to save it from the bane of human persecution, which has been inflicted upon wolves of all shapes and sizes throughout their geographical range. For decades, shamanus were feared, in spite of their small size, and hunted accordingly. Further depletion resulted from rabies, which first reached Japan from overseas in 1732, plus the destruction of the shamanu’s forest home for cedar replanting. And so it was that whereas its bonsai trees are today flourishing not only in their native land but also throughout the world, Japan’s dwarf wolves had been harried into extinction by 1905.

On January 23, 1905, Stanford University zoologist Malcolm Anderson, visiting Japan as part of a research team sent by London’s Zoological Society and the British Museum, was offered for sale the recently killed corpse of a shamanu by three hunters at Washikaguchi, Nara Prefecture. For the lowly sum of eight yens 50 sens, he purchased it, and sent its skin to the British Museum, where it has remained ever since. Today, the Washikaguchi shamanu’s value is incalculable, because it constitutes the last confirmed specimen on record.

But is the shamanu really extinct? Although it rarely rates a mention nowadays in Western zoological literature, there is a sizeable corpus of material in Japanese publications suggesting that this curious little canid may well have lingered on into the present day.

Probably the most extensive single source of such material is Yanai Kenji’s book,

Visionary Japanese Wolves

(1993). Kenji was inspired to prepare the book by the previous lack of detailed, readily accessible information dealing with the shamanu, and, especially, by his own sighting, at the age of 48, of what he believed to be a surviving shamanu.

It was early morning on the first Sunday of June 1964 when, as an enthusiastic amateur mountaineer, Kenji was journeying with his son and a colleague to the Ryogami Mountain. After hearing a series of spine-chilling howls, the trio suddenly spied a mysterious canine creature that was as big as an alsatian. They were able to observe the animal closely for a few minutes before it eventually disappeared, and afterwards they discovered a half-eaten hare nearby that it had probably killed just before they had arrived on the scene.

Professor Fujiwara Shizuo, from Tokyo University’s Department of Science, was convinced that Kenji had indeed seen a shamanu. Others, conversely, were more skeptical. Certainly, if the creature was the size of an alsatian, I find it difficult to believe that this could have been a shamanu. However, as documented in Kenji’s book, he is not the only investigator to support the possibility of this distinctive canid’s continuing survival.

Folklorist Yanagida Kunio, for instance, has written that the shamanu still existed as late as autumn 1934 in Oku-Yoshino, Nara Prefecture, a view also subscribed to by his assistant, Kishida Hideo. Moreover, Gokijo Yoshinori, who lived in the village of Shimo-Kitayama, Nara Prefecture, claimed that shamanus were still dwelling after World War II in the mountains stretching from the Odaigahara Heights to the Ornine Heights in the Kii Peninsula. In 1970, journalist Hida Inosuke actually claimed to have photographed one of these mini-wolves at night in the Ornine Heights—which, together with the Odaigahara Heights, is the locality offering the greatest probability of shamanu survival, in Kenji’s opinion.

According to another shamanu investigator, Seko Tsutomu, an animal greatly resembling one of Japan’s supposedly long-lost dwarf wolves was sighted by Saratani Takehiro on a cliff on the side of a dam in Nara Prefecture even more recently—in 1985.

Elsewhere in Japan, veterinary surgeon Oura Yutaka averred that in 1934, the shamanu still existed in the mountains bordering Fukushima, Yamagata, and Niigata Prefecture. And Kuno Masao drew a sketch of the shamanu that he allegedly spied in the Kumotori-Yama Mountain, situated on the border of Tokyo, Saitama, and Yamanashi Prefecture.

Not everyone, however, is convinced by this anecdotal evidence. Some Japanese zoologists believe that reports of shamanus merely derive from misidentifications of feral dogs. Certain others have wondered whether the creatures being seen might actually be hybrids, descended from original matings between pre-1905 shamanus and domestic dogs, but this proposed identity was ruled out by Dr. Hiraiwa Yonekichi, an eminent authority on the wolf.

Rather more tangible, yet no less tantalizing, is the preserved specimen of a shamanu that was discovered in January 1994 at a shrine in Kokufu-Machi, Tottori Prefecture—for it has been claimed, but not proven, that this specimen was presented to the shrine in 1950.

Nevertheless, its discovery revitalized public interest in the shamanu, which in turn led to the staging on March 19 and 20,1994, of the 1st Japanese Wolf Forum, a two-day symposium held at Higashi-Yoshino’s town hall in Nara Prefecture, and sponsored by the Nara Committee of Wild Life Conservation. As reported in a

Nihon Keizai Shimbun

newspaper report from March 20, 1994, about 80 shamanu researchers and other interested individuals from all over Japan participated in this event, which featured the testimony and recollections of hunters, mountaineers, and others with reports attesting to the shamanu’s post-1905 persistence. Even a sample of alleged shamanu feces was presented by one investigator to the Committee, and following the extent of interest generated by the symposium, plans were drawn to entice shamanus into view by using imported Canadian wolves as lures.