The Beasts that Hide from Man (30 page)

Read The Beasts that Hide from Man Online

Authors: Karl P.N. Shuker

In January 1997, a significant new piece of evidence for the shamanu’s putative survival was publicized, a series of recent photographs depicting a dog-like beast that bears a startling similarity to a living shamanu. The photos were snapped on October 14, 1996, by 47-year-old Hiroshi Yagi in the mountain district of Chichibu. He had been driving a van along a forestry road that evening when a short-legged dog-like beast with a black-tipped tail suddenly appeared further down the road. A longstanding shamanu seeker, Yagi reached for his camera, but the animal vanished. After driving back and forth along the road in search of it, however, Yagi saw it again, and this time was able to take no fewer than 19 photos from just a few feet away. He even threw a rice cake toward it, hoping to tempt it closer still, but the creature turned away and disappeared into a forest. When the pictures were examined by eminent Japanese zoologist Prof. Imaizumi Yoshinori, he felt sure that the animal was indeed a shamanu.

In November 2000, Akira Nishida took a photo of a canine mystery beast on a mountain in Kyushu that was widely acclaimed afterwards as evidence of shamanu survival—until March 2001, that is. For that was when a sign appeared on a hut on Ogata Mountain claiming that the creature in the photo was nothing more than a Shikoku-region domestic dog that the hut’s owner had been forced to abandon for private reasons. However, Yoshinori Izumi, a former head of the National Science Museum’s animal research section, dismisses this claim as a hoax, and remains adamant that the photographed canid is a bona fide shamanu, even stating that the pattern of the creature’s fur is completely different from that of Shikoku dogs. This is evidently a saga with many more chapters still to be written.

Yet the shamanu’s rediscovery would be a major cryptozoological event, so we await further news with great interest. Perhaps the howling god has not been silenced after all.

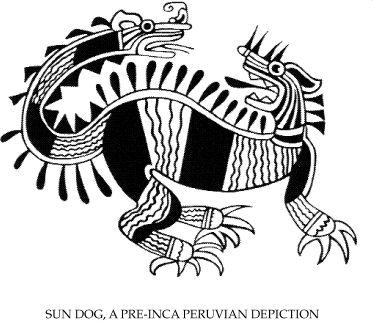

Iconography can sometimes be a fruitful source of material for cryptozoologists. Several notable modern-day species of animal, including the gerenuk (giraffe antelope), Roxellana’s snub-nosed monkey, and Gravy’s zebra, were first made known to science not via the procurement of a specimen, but by depictions on ancient monuments. Nevertheless, attempting to identify a creature portrayed in this manner can be fraught with difficulties, as exemplified by the little-known but highly intriguing case of the Mexican sun dog.

This mysterious sacred beast is depicted in numerous paintings, carvings, woven textiles, and ceramics preserved from the bygone Mexican civilizations of the Toltecs and Aztecs, as well as the Central American Mayas, and even the Peruvian Incas. Although varying quite extensively in appearance from one site to another, the sun dog was undeniably canine in form. It generally sported a slender lengthy body, four fairly short legs whose feet were equipped with noticeable claws, a long slender tail sometimes specifically portrayed as alive, an elongate muzzle, and a long extended tongue. What might it be?

If a living specimen could somehow be obtained, its identity would soon be ascertained—or would it? In

Americas Ancient Civilisations

(1953), writer Hyatt Verrill revealed that while residing in Ixtepec, southern Mexico, he was given a small animal that he felt sure was a young specimen of the Mexican sun dog. A new dawn for this ostensibly extinct enigma?

Brought to Verrill by a Lacandon Indian from Chiapas, the creature was just under two feet long, with a shortish face but lengthy slender tongue, sharp claws on its feet, short legs, a long prehensile tail, and golden-brown fur (paler ventrally). Most distinctive of all, however, was its long undershot lower jaw, jutting forth beyond the limit of its upper jaw.

The creature also possessed a facial mask, whose precise form was curiously inconsistent. Within his book, Verrill included two illustrations of his supposed sun dog pet. One was a photograph, the other was a drawing penned by Verrill himself. In the photo, the creature’s mask appeared to be much paler than the fur surrounding it. Yet in Verrill’s drawing, it was decidedly darker than the fur surrounding it, and resembled the black mask of a raccoon.

According to Verrill, his pet sun dog (which he nicknamed “the Monster”) was very ferocious, despite its modest size and tender age, and was only too willing to attack anyone without the slightest provocation, accompanied by dramatic snarls and hisses.

I first learned of the Mexican sun dog and Verrill’s pugnacious pet in September 1992, when one of my correspondents, Bob Hay from Augusta, Western Australia, sent me a copy of the relevant section from Verrill’s book, containing several different ancient depictions of the sun dog, and asked my opinion regarding the living animal’s identity. The ancient depictions were very interesting, and did not appear to correspond readily with any known creature alive today. As for Verrill’s pet, conversely, this was, for me, a disappointingly mundane Monster, with scant resemblance to the sun dogs or any other canine beast.

Indeed, it seemed to be nothing more than a young specimen of

Potosflavus

, the kinkajou. Also called the honey bear, and measuring up to four feet long when fully grown, this golden-furred relative of the raccoons, coatis, and other procyonids has a wide distribution, extending southwards from eastern Mexico to the Mato Grosso of central Brazil—and offers a near-exact morphological match with Verrill’s pet as portrayed in the photograph. Moreover, the kinkajou is the only member of the Carnivora in the whole of the New World with a prehensile tail. Not even its lesser-known lookalike relations, the olingos

Bassaricyon

spp., which are very similar to it in superficial external appearance, have a prehensile tail.

In fact, the only outward discrepancies between the kinkajou and the Monster were the latter animal’s lower jaw and its savage behavior. Yet even these can be satisfactorily explained. The Monster’s odd lower jaw is assuredly an abnormality—either a malformation resulting from a genetic or developmental quirk, or the product of some accident experienced by this animal, subsequently resulting in the jaw’s aberrant growth. Furthermore, if such an abnormality hampered its feeding or caused pain, this could well explain the Monster’s aggressive attitude. Alternatively (or additionally?), the Monster may have been treated harshly by its Indian captor, thus creating a frightened animal perpetually on the offensive.

The Monster’s intimate morphological correspondence to the kinkajou makes it all the more surprising that in his book, Verrill claimed that no zoologist had been able to identify his pet. Also, he personally ruled out any likelihood of taxonomie synonymity between this individual and either an olingo or a kinkajou (even a malformed one) because, he claimed, the Monster possessed a different (but unspecified) dentition. Yet if its lower jaw was a genetic or developmental malformation, this in turn could have affected its dentition too.

To my mind, the fundamental flaw with this entire history is Verrill’s assumption that his Monster belonged to the same species as the depicted sun dogs. As far as I can see, one was nothing but a young, possibly slightly deformed kinkajou, whereas the others probably owe more to the exceedingly elaborate, highly stylized artistry of long-vanished civilizations than to any bona fide mystery beasts still eluding formal identification and classification.

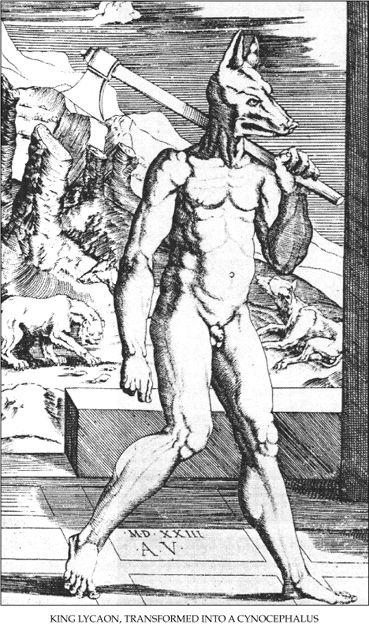

In medieval times, scholars firmly believed in the reality of all manner of extraordinary semi-human entities, supposedly inhabiting exotic lands far beyond the well-explored terrain of Europe. Prominent among these tribes of “half-men” were the cynocephali or dog-headed people, popularly referred to by travelers and chroniclers. Their domain’s precise locality, conversely, depended to a large extent upon the opinion of the specific traveler or chronicler in question, as few seemed to share the same view.

According to the Roman scholar Pliny the Elder (23-79 AD), the mysterious country of Ethiopia, which he mistakenly assumed was one and the same as India, was home both to the cynocephali and to the similarly dog-headed cynamolgi. Numbering 120,000 in total, the cynamolgi wore the skins of wild animals, conversed only via canine barks and yelps, and obtained milk, of which they were very fond, not from cows but by milking female dogs.

Several centuries earlier, Herodotus (c.485-425 BC), a Greek historian, had claimed that a race of Ethiopian dog-heads termed the Kynokephaloi not only barked instead of speaking, but also could spew forth flames of fire from their mouths!

Later authors often stated that India and nearby islands were populated by cynocephali. The 13th century Venetian traveler Marco Polo, who could never be accused of letting a good story slip by unpublicized, soberly announced that the Andaman Islands off Burma (now Myanmar) were home to a race of milk-drinking, fruit-eating (and occasionally man-devouring) dog-heads who engaged in peaceful trade with India. A century later, Friar Odoric of Pordenone relocated these entities to the nearby Nicobar Islands, whereas Friar Jordanus’s writings deposited them rather unkindly in the ocean between Africa and India. Cynocephali living in India itself were reported by geographer Peter Heylyn, who traveled widely during the time of Charles I, the Interregnum, and the Restoration of Charles II.

Nor should we forget Sir John Mandeville, even though his (in)famous supposed journeys to incredible faraway lands in Africa and Asia during the 14th century owe considerably more to the imagination than to peregrination. He averred that a tribe of hound-headed people inhabited a mysterious island of undetermined location called Macumeran. Here, curiously, they venerated an ox, and were ruled by a mighty but pious king, who was identified by a huge ruby around his neck and also wore a string of 300 precious oriental pearls.

Less well known than the above-mentioned examples is the fact that dog-headed entities also feature in Celtic lore and mythology. As pointed out by Prof. David Gordon White in his definitive book,

Myths of the Dog-Man

(1991), Irish legends tell of several cynocephalic people. Perhaps the most notable of these legends concerns a great invasion of Ireland from across the western sea by a race of dog-headed marauders known as the Coinceann or Conchind, who were ultimately vanquished by the hero warrior Cúchulainn. Irish legends also claim that St. Christopher was a cynocephalus; and a tribe of dog-heads opposed King Arthur, and were fought by him (or Sir Kay, in some versions of this tale).

Shetland folklore tells of a supernatural entity known as the wulver, which has the body of a man but is covered in short brown hair and has the head of a wolf. According to tradition, this semi-human being lives in a cave dug out of a steep mound halfway up a hill, and enjoys fishing in deep water. Despite its frightening appearance, however, the wulver is harmless if left alone, and will sometimes even leave a few fishes on the windowsill of poor folk. A similar wolf-man entity is also said to exist in Exmoor’s famous Valley of the Doones.

Cynocephalic deities are not infrequent in mythology, and include such familiar examples as Anubis, the Egyptian jackal-headed god of the dead; and the Furies or Erinnyes, the terrifying trio of avenging dog-headed goddesses from Greek mythology. Originally, Anubis was the much-dreaded god of putrefaction, but in later tellings he became transformed into a guardian deity, protecting the dead against robbers, and overseeing the embalming process. His head’s form was derived from the jackals scavenging in Egyptian burial graves during the far-distant age preceding the pyramids when graves were shallow and hence readily opened.

The Furies were the three hideous daughters of the Greek sky god Uranus and Gaia (Mother Earth), comprising Alecto, Megaera, and Tisiphone. Not content with canine heads, they also sported leathery bat-wings, fiery bloodshot eyes, foul breath, and hair composed of living serpents. Their allotted task was to harangue and punish evil-doers, especially parent-killers and oath-breakers, but eventually they were transformed into the kinder Eumenides.