The Best of Gerald Kersh (13 page)

Read The Best of Gerald Kersh Online

Authors: Gerald Kersh

The machinery that made the eyes and the head move and the hands tremble was nothing: a mere toymaker’s job. I always liked difficult, intricate pieces of work. So it occurred to me that it might be really amusing to fix the jointed figure so that it could stand up and even take a few stiff rheumaticky paces backwards and forwards. That also was easy – hawkers in the street sell tin toys which can do that very thing; and even turn somersaults. No, it was not complicated enough for me.

Having made the dummy tremble and blink and sit and stand and walk, I now wanted to make it talk.

Well, you know that the phonograph had been

invented

then, although it was a very crude affair and did not sound real. But then again, neither did the King’s voice sound real – in fact it sounded rather like a scratchy old phonograph record. Also, the King’s voice was the easiest thing in the world for any man to imitate. You can imitate it yourself if you like. Let a lot of saliva run to the back of your throat and groan – there is the King’s voice. I say once again, it was easy. The entire mechanism fitted into the back of the figure between the shoulder-blades and the hips, and was operated by several levers. If you pressed one, the figure stood up. If you pressed another, it walked twelve paces forward and

turned on its heel. So if you wanted the figure to pace up and down all you had to do was repeat the pressure on that lever.

Another lever made it sit down. As the thighs and legs made an angle of ninety degrees, the phonograph

automatically

started. Choking imprecations, together with groans of pain came out of the mouth. All the time the dummy shook and quivered, while a perfectly simple, concertina-shaped bellows inside the head sucked in the air and blew it out, so that the moustache that concealed the mouth was constantly in motion, and you could hear a kind of wheezy breathing.

It was all quite life-like, especially when we dressed it in clothes which we borrowed from the King’s wardrobe. As the King’s Clockmaker, I was a person of great

consequence

in the Palace. Everybody knew what had

happened

to Tancredy; they all went out of their way to be polite to me. I could even have had intrigues with Duchesses if I had been so disposed. I had no difficulty in getting from the Master of the King’s Wardrobe a complete outfit of the royal clothes, including fur slippers, a sable dressing-gown and a round velvet cap such as His Majesty invariably wore. When the dummy was dressed we sat it in a deep red velvet chair in the workshop, covered it with a sheet, and waited. At last the moment came. De Kock and I were excited, like children who have prepared a wonderful surprise for a beloved parent and are impatient to reveal it.

The King came in, with his doctor and his attendant holding him up, and was lowered, groaning and cursing, into his usual chair.

‘What have you got there?’ he asked.

I said: ‘A little surprise for Your Majesty.’ Then I

pressed two of the levers and whisked away the sheet all in one movement, and the dummy got up, walked twelve paces, which brought it face to face with His Majesty, and turned scornfully on its heel. I had measured my distance. Following it, I pressed another lever and it walked straight back to the chair and turned on its heel again. Another touch and it sat down, and the

gramophone

started and the great groaning voice bellowed dirty language right into the King’s face.

I looked towards him laughing in anticipation of his delight, but what I saw horrified me. His face had

become

blue. His eyes seemed to be trying to push

themselves

out of their sockets. His mouth opened, and he uttered a terrible rattling scream. I still hear that scream in my dreams.

‘Your Majesty,’ I cried, ‘forgive me!’

But he did not hear me. He fell back, and seemed to shrink like a sack of flour ripped open with a knife; and the old doctor, with a face as blue and terrified as the old King’s, felt his heart and stammered: ‘Oh, my God! Oh, my God! Oh, my God! He’s dead – the King is dead!’ And I remember that the sturdy attendant, bursting into tears, threw himself on his knees and cried: ‘Oh, Your Majesty, Your Majesty! Don’t go without me! Take me with you! Oh, Your Majesty!’ He shouted this a heartbroken voice, something like the howl of a dog in the night. Then I heard footsteps; the door opened. I saw Kobalt with a dozen others behind him. Kobalt naturally looked first towards the King’s chair, and when he saw what was there, the blood ran out of his face. Yet he was a quick-thinking man, even at a moment like this. He swung round and shouted: ‘Back to your posts! God help the man I find in this corridor! Colonel

of the Guard, a double guard on the outer gates – no one leaves the Palace!’

After that he slid into the workshop, shut the door, approached the royal chair and said: ‘Doctor Zerbin – is His Majesty——?’

‘His Majesty is dead,’ said the doctor, with tears on his face. I felt that it was I who had killed the King and I said: ‘Your Highness, it was all well meant. His Majesty asked us, de Kock and me, to make a figure, for a joke. The King wanted to——’

Kobalt turned, quick as a snake, with murder in his eyes. But then he saw the figure in the chair and his mouth hung open. He looked from it to the dead King. You know how death changes people. His Majesty, poor man, was all shrunk and shrivelled and blue, and looked somehow less than half as big as he had been five minutes before. The dummy, in every hair and every baggy pouch and wrinkle, was the image of the King as he had been when he was alive. Kobalt came slowly

towards

me. I never was a brave man, and loathe violence. I thought Kobalt was going to kill me, and all in a rush I said: ‘Don’t be hasty! De Kock and I are perfectly innocent, I swear it. His Majesty wanted a waxwork figure just to play a trick. A figure … like this….’

And I pressed levers. I made the wax image of Nicolas III stand up. It walked twelve rheumaticky paces, looked at the corpse of the King, turned on its heel, strode back, sat down groaning and trembling, and puffed at Kobalt all the vile words you have ever heard, in a voice like the voice of His Majesty. Then it was still, except for a swaying of the head and a continuous tremor. In a quiet place, of course, anyone could have heard the noise of

the powerful clockwork that made it move. But in the Palace of poor King Nicolas III, where there were more than seven hundred clocks, the noise of cogs, ratchets and pendulums was perpetually in everybody’s ears; even the members of the kitchen staff when they were out imagined that they were still hearing the ticking of clocks.

Kobalt actually bowed to the image and started to say: ‘Your Majesty,’ but he stopped himself after the first syllable, and said: ‘How very remarkable!’

‘It is only a doll,’ said de Kock, and there was a

certain

gratification mixed with the terror in his voice, ‘a wax doll, a mere nothing.’

‘It looks real enough,’ I said, pressing the levers again; whereupon the figure got up, stood, walked twelve paces, turned, walked back, sat, groaned with agony and damned our eyes. Kobalt touched its wax forehead and shuddered. He went over to the King and felt his hand. Then his keen eyes veiled themselves. I could see that he was thinking hard and fast. It was not difficult to guess what was in his mind; the end of the King was the end of Kobalt. He, too, was as good as dead.

Soon he looked at me and said: ‘You made this machinery, did you? I want to have a word with you. And you, Monsieur de Kock, you made this waxwork figure? For the moment it deceived me. You are a very talented man, Monsieur de Kock … and His Majesty collapsed on seeing your little work, gentlemen? Few artists live to boast of a thing like that.’

If he had simply said: ‘Few artists can boast of a thing like that,’ I might not be here to tell you this story. But when he said

‘live

to

boast,’

I knew that there was

something

wicked in his mind. I knew that I was in frightful danger. Poor de Kock was already beginning to swell up like a pigeon, rolling his eyes and pushing out his chest. Kobalt went to a speaking-tube and blew into it, and then he said: ‘Major Krim? … Come down here at once with four or five men upon whom you can rely.’ Turning to me he said: ‘When I give you the word, make that thing work again.’

With an air of reverence – smiling now – he threw the sheet with which we had covered the dummy over the dead body of King Nicolas. Footsteps sounded. ‘Now!’ said Kobalt to me and I pressed levers. Major Krim, a man with a scarred face, came in with four others. As they entered, the dummy got out of the chair and walked abstractedly a few paces while Kobalt, keeping a wicked eye on me, said: ‘His Majesty commands that the Dr Zerbin and the attendant Putzi be put under arrest

instantly

, and kept

incommunicado

.’

The thunderstruck doctor and the grief-stunned attendant were taken away. As the door closed the

unhappy

Putzi began to weep again, looking back over his shoulder at the thing covered by the sheet.

‘Oh, you may well cry, you scabby dog!’ shouted Kobalt, and then the image sat down groaning and quivering with the inevitable asthmatic curses, and the door closed.

Kobalt opened it again very quickly and glanced outside; shut it again and locked it, and said to me: ‘What a very remarkable man you are, my dear M. Pommel, to make something like that. Why, it is almost – if I may say so without irreverence – almost like God breathing the breath of life into clay. How does it work?’

I have always been a timid and obliging man, but now – thank God – something prompted me to say: ‘Your Highness, that is my secret and I refuse to tell you.’

Kobalt still smiled, but there was a stiffness in his smile and a brassy gleam in his eyes. He said: ‘Well, well, far be it from me to pry into your professional secrets – eh, M. de Kock? … How wonderful, how marvellous – how infinitely more important than the death of kings, who are only human after all and come and go – how very much more important is the work that makes a man live for ever! To be a great artist – only that is worth while. Ah, M. de Kock, M. de Kock, how I envy you!’

Poor foolish de Kock said: ‘Oh, a mere nothing.’

He had been drinking Plum Brandy. His vanity was tickled. I could not help thinking that if he had a tail he would wag it then.

‘How

does

that work?’ asked Kobalt, and the very intonation of his voice was a gross flattery. I could not stop looking at the body of the King under the sheet; but de Kock, full of pride, said: ‘What do I know of such things? Your Highness, I am an artist – an artist – not a maker of clockwork toys. Your Highness, I neither know nor wish to know, nor have I the time to get to know, the workings of an alarm clock.’

In quite a different tone of voice, Kobalt then said: ‘Oh, I see.’ And so he gave another order, and Major Krim conducted de Kock to his suite, where, three weeks later, he was found with his brains blown out and the muzzle of a pistol in his mouth. The verdict was suicide: de Kock had emptied three bottles of a liqueur called Gurika that day.

But that is not the point. As soon as the Major had led de Kock out of the workshop, Kobalt began to talk to me.

Oh, that was a very remarkable and a very dangerous man! You were asking me about de Kock, earlier in the evening, and I said that I was not quite sure whether poor Honoré really committed suicide. Well, thinking again, I am convinced that he did not. The butt of the revolver was in his hand, the muzzle was in his mouth, and his brains were on the wall. There was one peculiar aspect of this suicide, as it was so called: the revolver was held in de Kock’s right hand, and I happened to know that he was left-handed. It seems to me that he would have picked up his revolver with the same hand that he used to pick up the tools of his trade. A man dies, if he must, as he lives – by his best hand. And then again: Dr Zerbin and the attendant Putzi disappeared.

I beg your pardon, all this happened later. I was

telling

you that when I was alone in the workshop with Kobalt, he talked to me. He said that he would give me scores of thousands, together with the highest honours that man could receive, if I would communicate to him the secret of that unhappy dummy that de Kock and I had made to amuse the King who now crouched dead in his chair. I have always been timid but never a fool. I became calm, extremely calm, and I said:

‘I think I see your point, Your Highness. Without His Majesty, you are nothing. Naturally you want to be what you are and to save what you have – you want to be, as it were, the Regent in everything but name. If the news of His Majesty’s death reaches Tancredy, you are out. You may even have to run for your life, leaving many desirable things behind you. Yes,’ I said, ‘I believe that

I can see to the back of your scheme. Once you are acquainted with the working of this doll, you will work it. King Nicolas III, the poor old gentleman, was the Father of his country, with half a century of tradition behind him. As long as King Nicolas could show himself to the people, the monarchy was safe. And as long as the monarchy was safe, you were great. This dummy here looks so much like His unhappy Majesty that even you, at close quarters, were deceived for a moment. If the real King had not been sitting over there, you would never have known anything. I may go so far as to say that the figure de Kock made and I animated is even stronger than the King because it can stand up and walk of its own accord, which His Majesty could not; and say the same things in the same voice. It can even write His Majesty’s signature.’

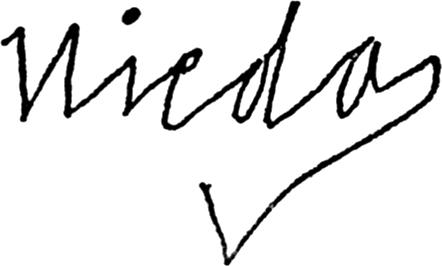

This, in point of fact, was perfectly true. The arthritic fingers of the King had no suppleness left in them, so that he wrote with his arm. Keep your arm stiff, grip a pen between the thumb and the first finger of your right hand, write the name

Nicolas

and you will see what I mean. Like this: