The Big Book of Pain: Torture & Punishment Through History (23 page)

Read The Big Book of Pain: Torture & Punishment Through History Online

Authors: Daniel Diehl

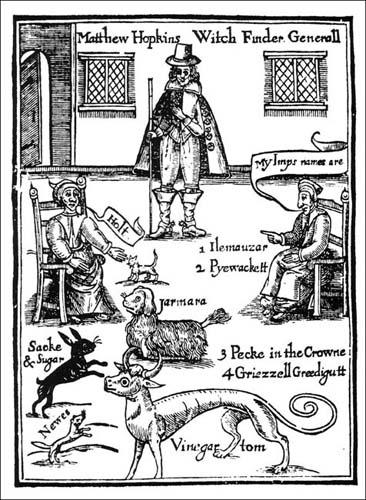

The frontispiece to

Discovery of Witches

(1647) by Matthew Hopkins, Witch Finder General of England. He kept Elizabeth Clarke awake in her cell for four days. These are the animal ‘familiars’ which she reported seeing in that time. Based on this testimony, she was executed for witchcraft.

With half a dozen more witches now named, and more names pouring forth with each round of torture, Hopkins added three new members to his team, including Mary ‘Goody’ Phillips, an expert witch-pricker. Unlike most prickers, who had to poke and prod for hours until the victim confessed or failed to feel pain, Hopkins supplied Phillips with a prick with a retractable needle; it was completely painless and appeared as though the needle was being sunk deep into the victim’s flesh. It was a cheap stage trick, but it purchased the lives of dozens of women.

Pricking was not the only way Hopkins could identify a witch; he insisted he could tell just by the way a woman threw her hair over her shoulder or how she interlaced her fingers whether or not she was having sex with the Devil. In a matter of months Hopkins was the talk of southern England and even the reactionary parliamentarian newspaper

The Scottish Dove

lauded his work, claiming that under Hopkins’ questioning: ‘The witches do confess they had been in the King’s Army and have sent out their hags to serve them … His Majesty’s Army, it seems, is beholding to the Devil’. Other papers ghoulishly reported on the supposed offspring brought about by the Devil’s coupling with witches. Some described limbless Cyclopes while others insisted they were two-headed, eight-limbed cats with human hands. No wonder then that requests poured in from all over East Anglia for the services of Matthew Hopkins, who now styled himself Witch-Finder General of England.

Hopkins not only charged ‘by the head’ for every witch discovered, but in many places he ordered local authorities to levy special taxes to pay his expenses and his helpers’ wages. But it must have seemed like it was worth every penny because everywhere Matthew Hopkins went dozens of witches would be discovered, arrested, tortured into confessing, tried according to law and publicly executed. Of thirty-four women slated for trial at Colchester in July 1645, four died in prison, one (a teenager) was released when she agreed to testify against the others, and the remaining twenty-nine were hanged.

Some of the confessions elicited by Hopkins demonstrate that not only can a person be tortured into confessing to almost anything, but just how willing the public and courts must have been to accept such obviously forced testimony. Margaret Wyard insisted the Devil came to her bed in the guise of a handsome young man with blond hair, but Elizabeth Chandler claimed that when he came to her it was in the shape of ‘roaring things’ that ‘slithered into her bed in a puffing and roaring manner’. Disagreeing with both of these was the testimony of an old woman who said her demonic lover was nothing less monstrous than two gigantic beetles. It is hardly surprising that Hopkins’ victims would confess to anything. In his notes on the torture of the septuagenarian Rev. John Lowes, who at first staunchly denied any wrongdoing, Hopkins wrote: ‘We kept him awake several nights together while running him backwards and forwards about his cell until he was weary of life and scarce sensible of what he said or did’. Hardly surprising then that Rev. Lowes finally confessed to giving birth to, and suckling, four little demons as well as conjuring up a storm that caused a ship to sink, with a loss of fourteen lives. Lowes’ retraction did him no good and no one ever checked to see if a storm, and the associated shipwreck, had taken place. Rev. Lowes was hanged in August 1645.

By late autumn of that year, Hopkins had brought about the executions of nearly 200 people, had an equal number behind bars and no one knows how many had died in prison. When Hopkins offered to visit the village of Great Staunton in Huntingdonshire, however, all did not go as planned. A member of the town council showed Hopkins’ letter to the local vicar, John Gaul, and Gaul promptly denounced Hopkins from the pulpit, and in a pamphlet, where he said: ‘Every old woman with a wrinkled face, a furrowed brow, a hairy lip, a squeaking voice or a scolding tongue, having a ragged coat on her back and a dog or cat by her side is not only suspected but pronounced for a witch’. Soon, even some in Parliament began questioning Hopkins’ tactics, if not his motives. One unbiased London newspaper wrote: ‘Life is precious and there is need of the greatest inquisition before it be taken away’. By Christmas, Hopkins’ services were no longer being requested and his reign of terror was over. In nineteen months he had judicially taken the lives of more than 230 people.

Samuel Butler’s satire

Hudibras

commented on Hopkins’s activity, saying:

Has not this present Parliament

A Lieger to the Devil sent,

Fully impowr’d to treat about

Finding revolted witches out

And has not he, within a year,

Hang’d threescore of ’em in one shire?

Some only for not being drown’d,

And some for sitting above ground,

Whole days and nights, upon their breeches,

And feeling pain, were hang’d for witches.

And some for putting knavish tricks

Upon green geese and turky-chicks?

And pigs, that suddenly deceast

Of griefs unnat’ral, as he guest;

Who after prov’d himself a witch

And made a rod for his own breech.

The last line refers to a tradition whereby disgruntled villagers caught Hopkins and subjected him to his own ‘swimming’ test: he floated, and therefore was hanged for witchcraft himself. However, it is believed by most historians that Hopkins actually died of illness (possibly tuberculosis) in his home. The parish records of Manningtree in Essex record his burial in August of 1647.

Matthew Hopkins may have been the most notorious of the witch hunters, but he was neither the first nor the last. Four years later, in 1649, a Scotsman named John Kincaid – the most celebrated witch-pricker of his day – was called to Newcastle-upon-Tyne where he was paid 20

s

for every person he could get convicted of witchcraft. On his arrival in the city, the town crier walked the streets calling for informers to present their suspicions to Kincaid at the town hall. Of the thirty women accused of practicing the black arts, twenty-seven were convicted and executed.

By the late 1650s, England had grown tired of witch hunting, Puritans and Oliver Cromwell’s brand of law and order. Cromwell himself died in 1658 and Richard Cromwell, his son and heir, known even to his father as ‘Tumble Down Dick’ was unable to hold the Puritan government together. In 1660, King Charles II was recalled from exile and meekly handed his late father’s crown. Being a fun-loving sort of guy himself, Charles repealed the Puritanical laws against gambling, drinking, dancing and general merry-making. He also had the rotting bodies of Cromwell and his cohorts exhumed and hanged as an example to others who might feel the urge to chop off a monarch’s head. In a move toward religious tolerance, he severely limited the power of courts to try people on charges of blasphemy, heresy and other religious offences. The British court system in general, however, was still weighted heavily against anyone brought before the bar. Defendants were not permitted to present witnesses on their behalf nor have counsel to represent them – that was supposed to be the judge’s job – and only the crown had a prosecutor to plead its case. Unfortunately, in far too many instances the judge did little more than bolster the case for the prosecution.

All too aware that the cards were stacked against the accused, juries often leaned as far in the defendant’s favour as the court leaned toward their conviction. To prevent conviction, and the subsequent imposition of some unspeakably nasty punishment of a defendant, juries were likely to massively underrate the seriousness of a crime or the value of goods stolen in a robbery. Perjury, it seems, became a full-time profession with professional ‘witnesses’ and jurors vying to sell their services and testimony to the highest bidder. Known as ‘Straw Men’ these paid, expert witnesses wandered up and down in front of courthouses with bits of straw tucked into their shoe buckle – a subtle but easily recognisable form of advertising. Naturally, judges were well aware of such goings on, and were quick to sequester juries and threaten them with incarceration and starvation if they returned a verdict not to the court’s liking. This process of brow beating juries into cooperation reached its height during the short-lived reign of James II, Charles II’s younger brother, who ruled between 1685 and 1688. James’ court system, along with much of the government, was run by Judge George Jeffreys. The best description of the horrible Jeffreys came from the late King Charles, who had once said the judge possessed: ‘no learning, no sense, no manners and more impudence than ten whores’. King James, on the other hand, loved him.

Like a scene from some cheap horror movie, Jeffreys draped the walls of his courtroom with scarlet tapestries and accepted only one plea: ‘guilty’. Anything else was a complete waste of the court’s precious time. Even minor offences brought horrific punishments. Anyone foolish enough to stand up to Judge Jeffreys went to the block. Anyone impious enough to disagree with King James was sent down to Jeffreys, who sent them to the block. Anyone accused of petty crime would inevitably meet the hangman. When Jeffreys sentenced Sir Thomas Armstrong to the block without the benefit of trial, Armstrong demanded his right to due process. Jeffreys snapped back: ‘Then that you shall have, by the Grace of God.’ Turning to his bailiff he added: ‘See that [the] execution be done on next Friday following the trial’. When the handsome and popular young Duke of Monmouth accused King James of poisoning King Charles to grab the throne, Jeffreys went after Monmouth and his supporters, hunting them down and dispatching them to the noose or block by the hundreds.

At 10 a.m. on 15 July 1685, an armed guard escorted the Duke of Monmouth from the Tower to Tower Hill where he was to mount a scaffold draped in black bunting especially for the occasion. Along the route, more than 3,000 of the young duke’s supporters had gathered to witness the grisly spectacle. So fearful was the king of an attempt to rescue his nephew that he had ordered the guard to shoot Monmouth dead if there were any disturbances in the crowd before the execution was complete. For a man about to die, the duke’s manner was unnervingly calm and composed. When the entourage mounted the scaffold, the two bishops who accompanied the condemned man began a prayer. Although Monmouth dutifully repeated their words, he refused to pray for the salvation of the king, only muttering ‘amen’ when they had finished. In a break with established custom, he refused to make a final speech, handing a prepared statement to one of the bishops to read to the crowd. As he approached the block, he also refused the customary blindfold.

Before kneeling to place his head on the block, Monmouth calmly bent down and pulled the executioner’s axe from under a pile of straw. Lifting it up, he ran his finger along the edge and turned to the headsman, the notorious Jack Ketch, asking if he thought it was sharp enough to do the job properly. Staring at his victim with disbelief, Ketch was even more astonished when Monmouth handed him the exorbitant sum of 6 guineas, saying: ‘Pray, do your business well. Do not serve me as you did my Lord Russell. I have heard you struck him four or five times; if you strike me twice, I cannot promise you not to stir.’ He then turned to one of his servants and told him that if Ketch did a clean job he was to receive six more guineas. With that, he knelt down and placed his head on the block.

Ketch, unnerved by Monmouth’s calmness and casual attitude, completely bungled the job. When the first blow only grazed the back of the duke’s head, he turned his blood-covered face upward, staring directly into Ketch’s eyes. Two more blows had still not finished the horrid job and in anger and frustration Ketch threw down the axe, declaring that he would pay 40 guineas to anyone in the angry crowd who could do the job better. It was only when the Sheriff of Middlesex, who was standing on the platform, demanded that Ketch finish his job or be killed on the spot, that he retrieved the axe and struck another ill-aimed blow. According to an eyewitness, ‘the butcherly dog did so barbarously act his part that he could not, at five strokes sever the head from the body’. Finally, in exasperation, Ketch used his belt knife to sever the duke’s head from his body and put the condemned man out of his misery.