Read The Big Book of Pain: Torture & Punishment Through History Online

Authors: Daniel Diehl

The Big Book of Pain: Torture & Punishment Through History (44 page)

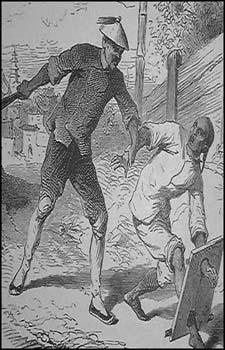

Public flogging

EGYPT

In Pharaonic Egypt, whippings were generally carried out with bundles of reeds. While this may sound like a fairly mild punishment, records indicate that in extreme cases the punishment could result in the death of the victim, usually as a result of post-punishment infection. The risk of infection setting into the dozens, if not hundreds, of open lacerations caused by a whip were a common side effect of whippings throughout all cultures until well into the nineteenth century.

Bastinado (caning the feet) in Persia.

PERSIA

Ancient Persian courts punished offenders with the

bastinado

, a lightweight whip made of reeds, wherein the convict had the soles of their feet slapped repeatedly with the whip. While this punishment was never considered lethal it would seem, judging from surviving records, that prolonged whippings could literally drive the victim out of their mind.

Flails

ROME

Although the Romans seldom punished free men and women with the whip, the varying types of Roman whips – each designed to inflict a different type, and degree, of physical damage – display an innovative cruelty seldom matched in history. These whips were used almost exclusively on slaves, prisoners of war, citizens of subject nations who transgressed Roman law and recalcitrant Roman soldiers. The Romans may well have been the first to make whipping a part of a greater punishment, such as by whipping a condemned person while they were being dragged to their execution. Most accounts claim that Jesus was scourged prior to his interview with Pontius Pilate, as well as on his way to the cross, with the

plumbatae

described below.

FERULA

For the most insignificant offences a simple, flat whip, known as the

ferula

, was employed and while it was undoubtedly painful and raised welts, the physical damage was temporary at worst.

SCUTICA

The

scutica

was a Roman whip made of braided strips of parchment which, like the world’s worst paper cuts, could flay the hide from a victim’s back with terrifying efficiency.

PLUMBATAE

The plumbatae were multi-thonged whips not dissimilar to the later cat-o-nine tails. On some occasions small lead balls were attached to the end of the thongs or thorns or tiny slivers of sharp metal were braided into the leather (in which case the whip was called the

ungulae

); any such variation was guaranteed to make the punishment vastly more painful and physically damaging.

FLAGELLUM

While nearly any whipping, if carried to the extreme, is capable of causing death, the Romans are the only society we have come across that had a whip designed specifically as a weapon of execution. Like a monstrous bull-whip, the

flagellum

could literally tear a victim to pieces. Frequently used as a combat weapon in the gladiatorial arena, the

flagellum

was also used to shred condemned groups of Christians before the leering crowds who gathered at ‘the games’ during the reign of Nero (54–68 AD).

CHINA

The Chinese, from ancient times until the fairly recent past, administered whippings with a whip made of lengths of split bamboo. Heavier and more substantial than the Egyptian reed whip, there is no record that the Chinese whipped to the point of death. The level of damage inflicted by Chinese bamboo whips – partly due to the limited number of lashes that were usually administered – seems to have been to turn the victim’s back, or upper thighs, into a mass of welts and blood-blisters. In both China and Japan, whippings were almost universally administered while the victim was laying, face down, on the ground. During the period of the Manchu dynasty (1644–1911) the art of the bamboo whip was developed to its most effective height. Manchu flogging masters were taught how to use their whip by flogging a block of Tofu (bean curd) until they could strike it without breaking the surface.

Chinese punishment of flogging through the streets.

JAPAN

Like the Chinese, the Japanese used whips made of split bamboo, but in Japan the strips of bamboo were arranged so the sharp edges of the strips were aligned outward. The effect of the razor-sharp bamboo on human flesh seems obvious enough. According to Japanese law, judicially imposed floggings could range from a few strokes up to no more than 150; but even at that point the survival of the victim was probably a matter of sheer luck.

Flogging post.

MEDIEVAL EUROPE

From the early Middle Ages through the eighteenth century, Britain and Europe punished lesser offences with a good, public whipping. The condemned party was generally tied, or manacled, to a public whipping post – conveniently painted bright red – thus ensuring that they could not try to escape while punishment was being administered. In some cases the whipping was only one facet of a larger, more complex punishment and might come during a specified period spent in the public pillory, or the whipping might be enhanced by having vinegar or salt rubbed into the open lacerations left by the whip – while both salt and vinegar would act as defence against infection, the pain of having such astringent substances ground into open wounds could well be as painful as the whipping itself.

ENGLAND

The Act Against Vagrants, passed in 1530, singled out one specific group whom the choleric King Henry VIII deemed to be in particular need of hard and regular floggings. To punish these vagrants (a catch-all term generally applied to Gypsies, vagabonds who wandered aimlessly from town to town and others who simply refused to work) an additional dimension was often added to the standard public whipping. The condemned party had their hands bound and were then tethered to the back of a cart with a length of rope; as the cart was led through the streets of the town the exposed back of the victim was whipped. The punishment could last as long as it took the cart to move from one specified place to another (i.e. from the local court to the village church) or until sufficient damage had been inflicted for the blood to run freely down the victim’s back and legs and leave a visible trail on the roadway.

Running the gauntlet.

Occasionally, even a punishment as straightforward as a whipping, could go completely, and sometimes hysterically, wrong. During the late eighteenth century, English poet William Cowper wrote a letter to a friend describing one such incident. ‘The fellow’, Cowper wrote,

seemed to show great fortitude; but it was all an imposture. The beadle [local watchman] who whipped him had his left hand filled with red ochre [a rust-coloured, dry pigment used in dyes and paint], through which, after every stroke, he drew the lash of the whip, leaving the appearance of a wound upon the skin, but in reality not hurting him at all. This being conceived by the constable, who followed the beadle to see that he did his duty, he (the constable) applied his cane … to the shoulders of the beadle. The scene now became interesting and exciting. The beadle could by no means be induced to strike the thief hard, which provoked the constable to strike harder; and so the double flogging continued, until a lass … pitying the beadle, thus suffering under the hands of the pitiless constable, seized him (the constable) … and pulling him backwards … slapped his face with Amazonian fury … the beadle thrashed the thief, the constable the beadle, and the lady the constable and the thief was the only person who suffered nothing.

During the eighteenth and nineteenth century, the British penal system developed nearly as numerous and creative forms of the whip as the Romans and all of the whips noted below were used mercilessly by prison guards, watchmen, beadles and others in authority, in an effort to keep the rabble in line.