The Big Book of Pain: Torture & Punishment Through History (41 page)

Read The Big Book of Pain: Torture & Punishment Through History Online

Authors: Daniel Diehl

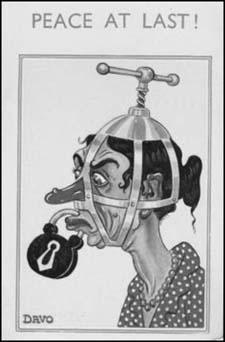

Scold’s bridle.

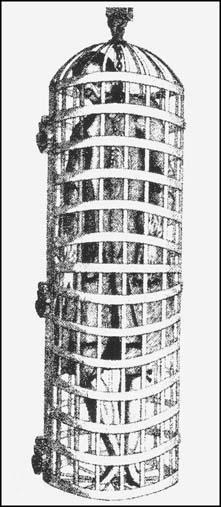

SCOLD’S BRIDLE

(See also Branks.) The scold’s bridle, like the ducking stool and the chucking stool, was a device intended specifically to punish sharp-tongued women, and was used throughout Britain and Europe during the Middle Ages. A helmet-like cage made of iron straps, the scold’s bridle was locked over a woman’s head, after which she might be led through the streets of the town and exposed to cat-calls and hoots of derision. To increase the pain, a metal tongue or ball might be forced into the woman’s mouth to gag her screams or curses during the punishment. From the records of Newcastle-upon-Tyne comes this account from 1665:

There he saw one Anne Bridlestone drove through the streets by an officer of the corporation, holding a rope in one hand, the other fastened to an engine called the branks … which was muscled over [her] head and face, with a great gag or tongue of iron forced into her mouth, which forced blood out …

Similar devices were used during seventeenth-century witch trials to keep the accused quiet while their fate was being decided by the court.

Postcard using scold’s bridle for humorous effect.

SIGNS OF SHAME

A more humane variation of branding practiced in the American Colonies was the custom of having transgressors wear a sign, or placard, that made their shameful behaviour evident to anyone they passed on the street. The most famous such sign is undoubtedly the red letter ‘A’, sewn to Hester Prynne’s dress in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s novel

The Scarlet Letter

. Unlike Hawthorne’s tragic heroine, the real Hester Prynne (who was tried and convicted in New Plymouth Colony in 1671) was not only convicted as an adulteress, but also as a drunkard. Her punishment was to wear both the letters A and D, denoting her double crime. In other instances, the punishment was more fully descriptive. In Boston in 1633, Robert Coles was fined 10

s

and sentenced to wear a sign with the single word ‘Drunkard’ and in 1650 a Connecticut man found guilty of insulting ministers and disrupting church services was forced to wear a sign reading ‘Open and Obstinate Condemner of God’s Holy Ordinances’. Similarly, Ann Boulder had to wear a sign stating that she was a ‘Public Destroyer of the Peace’. Presumably, if the condemned failed to wear the sign as instructed they would be charged with more serious offences or, at the very least, given a harsher punishment for the original. This idea of ‘naming and shaming’ is one which is finding favour among modern contemporary exponents for crimes ranging from shoplifting to child sex offences.

A brank in Lancaster Castle.

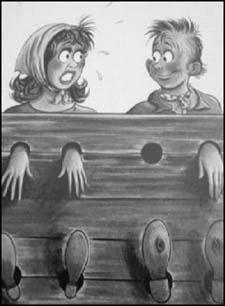

A postcard using punishment of stocks for humorous effect.

STOCKS

Roughly similar in structure and purpose to the pillory, the stocks were a hinged, wooden restraint into which a person’s ankles were locked. Also like the pillory, the stocks were of ancient origin (at least dating back to the Anglo-Saxon period) and located in public so the condemned was exposed to constant humiliation and abuse – an indication that they were not used to punish violent criminals, but to teach people a lesson in good manners and honesty. In an English law of 1426, it states that vagrants were to be locked in the stocks for a period of three days and nights and given only bread and water. A record dating from the mid-1500s tells us that in London ‘four women were set in the stocks all night till their husbands did come to fetch them’ and in eighteenth-century Boston, Massachusetts, Edward Palmer was fined and sentenced to spend one hour in the stocks for stealing a plank of wood. The stocks were less physically damaging than the pillory, but to make sure the victim was not too comfortable, they were often forced to sit on the edge of a narrow board while they endured their sentence. The early medieval French added another distressing dimension to the time spent in the stocks; the bottoms of the victim’s feet were doused with saltwater and a goat was allowed to lick them. It may have been hysterical for those watching but a goat’s tongue is as rough as sandpaper and after a very few minutes the pain became excruciating. The humiliation associated with being put in the stocks remains with us in the phrase, ‘being made a laughing stock’.

Stocks.

TORTURE BY STRETCHING AND SUSPENSION

CRUCIFIXION

Many early cultures, including the ancient Hebrews, used crucifixion as a means of executing their criminals, but it was the Romans who made this particularly slow death their specialty. How a man being crucified looks when he is hung on a cross needs no explanation; anyone who has ever been inside a Christian church is familiar with the image of Jesus suffering on the cross, but a few explanatory words of just what it was that killed the victim may be in order. Contrary to popular belief victims of Roman crucifixion were not always nailed to the cross – the weight of their suspended body would have ripped the nails through their flesh. The nails only increased the amount of pain they were forced to endure. Those condemned to crucifixion were tied to the cross while it lay on the ground and the entire affair was then hoisted upright and dropped into a hole deep enough to ensure that the cross did not topple over. In most cases there was a small platform beneath the victim’s feet which allowed them to take the weight off their arms, at least temporarily. Because the entire weight of the body hung from the victim’s wrists, the strain would eventually tear the muscles in their diaphragm, making it impossible to breathe. Anyone who refused to cooperate in their own death, insisting on standing on the small platform, would eventually have their knees broken with a long-handled sledgehammer. One way or another, sooner or later, breathing became impossible and the victim died of slow suffocation and exposure.

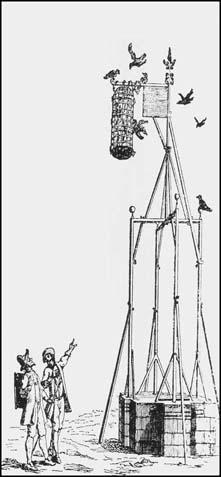

The pulley.

Gibbet.

GARRUCHA

The

garrucha

, also known as the strappado (

estrapade

in Spanish) and as the act of ‘Squassation’ was one of the Spanish Inquisition’s most popular forms of torture, but the same torture was used elsewhere, most notably in India and among the Japanese, where it was known as

Yet Gomon

. Although there were small variations, the basic principal of the

garrucha

involved the prisoner’s hands being bound behind their back and a rope running from the wrists was threaded through a pulley attached to the ceiling or a crossbeam. When the rope was hauled in the prisoner was lifted into the air while their arms were slowly pulled from the shoulder sockets. In some cases heavy stones, weighing anywhere from 100 to 250lbs, were tied to the victim’s feet as a means of increasing the pain, and in other instances the victim was repeatedly lifted and dropped to the floor, sometimes onto a mound of sharp rocks. Yet again, he might only be dropped a few feet, causing the body to jerk violently against the arm sockets. The practice seems to have been picked up by the Italians, who called it

strappare

, and the Germans who knew it as

Aufzehen

. This study in cruelty was recorded as still being in use in Italy as late as 1778.