The Big Music (47 page)

Authors: Kirsty Gunn

18

Various pages and documents sampled in this Crunluath A Mach show the intervention of Helen MacKay in this fashion as one who is piecing together a narrative from these various fragments – here, shown by a separate piece of her notepaper attached by paperclip to John Sutherland’s diary, in other places using Post-It notes, additional computer-written documents stapled to the back of an original file, or inserting handwritten notes into a file that also contains John Sutherland’s original material. In all instances it describes a highly original and intuitive approach to managing and responding to John Sutherland’s work and life. Each of her insertions seems to suggest a question more than an idea for reaching a conclusion. Each is like an opening door. As she writes herself, ‘Perhaps it [i.e. the scrap of paper that has been found] really is where the whole book begins.’

As noted in the Foreword of ‘The Big Music’, additional material is provided for the reader by way of various appendices and lists of information that relate to various aspects of the story that is being told. This ranges from background notes and a general history of the area of Sutherland in northern Scotland, where John Callum MacKay and his family have lived for generations, to details of the House there and its Piping School as well as information about bagpipes and bagpipe playing generally and its place in this book and in music and in art.

It is by no means necessary to read all or any of this material, it is simply a way in, for those who want to go there, to the landscape and world of ‘The Big Music’ – to indicate the hills at your back or the view that stretches ahead. As the preceding book was a place in which, for a time, you have lived, so may these pages extend its boundaries.

i

Historical geography

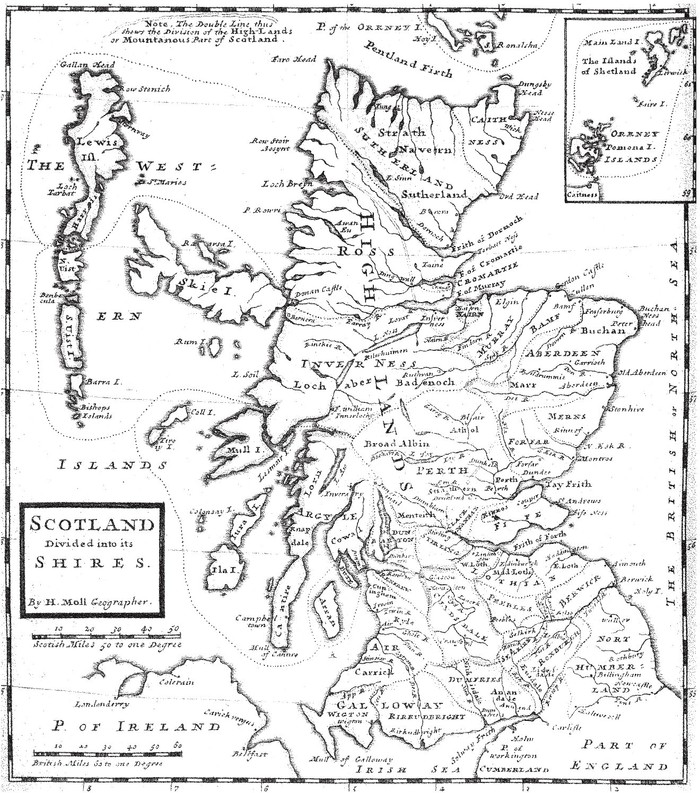

In geographical terms, the Highland area refers to the north-west part of Scotland that crosses the mainland in a more or less straight line from Helensburgh to Stonehaven – with the flat coastal lands that occupy parts of the counties of Nairnshire, Morayshire, Banffshire and Aberdeenshire often excluded, as they do not share the distinctive geographical and cultural features of the rest of the Highlands. In Aberdeenshire, the boundary between the Highlands and the Lowlands is not well defined. There is a stone beside the A93 road near the village of Dinnet on Royal Deeside which states ‘You are now in the Highlands’, although there are areas of Highland character to the east of this point.

The north-east of Caithness, as well as Orkney and Shetland, is also often excluded from the ‘Highland’ definition for the same reason of appearance – although the Hebrides are not. None of these definitions are, however, emotionally based, that is, giving a meaning carrying its own particular truth that can be just as descriptive as geographical precision, and when one refers to the Highlands as part of conversation or in a book or in a song or when pointing the way to a part of the country that feels remote and lost and far away … One is referring to a Highland region that is not so-defined by any geographer’s manual or map. To be high up, on a hill or mountain, surveying the whole empty sweep of the country below you – this is to be in the Highlands. As it is to be in a car or on foot upon a road that twists and turns and thins to the finest thread on an Ordnance Survey map that marks the topmost area of the British mainland … Then you are in the Highlands, too.

Another way the definition of the Highland area differs from the Lowland region is by language and tradition, as there are many Highland regions that have preserved Gaelic speech and customs centuries after Anglicisation. This has also led to a refining of that cultural distinction between Highlander and Lowlander that was first noted towards the end of the fourteenth century. Even so, there are many areas in the Highlands where Gaelic is not spoken but a great sense of regional difference prevails nevertheless, a sense of being Highland more to do with manner and way, a certain turn of phrase at times or a weighting and a rhythm in the speech and syntax. These kinds of sentences and attitudes, this sensibility, mean more in Highland terms than the actual language spoken.

Inverness is traditionally regarded as the capital of the Highlands, although less so in the Highland parts of Aberdeenshire, Angus, Perthshire and Stirlingshire, which look more to cities such as Aberdeen, Perth, Dundee and Stirling as their commercial centres. Nevertheless the phrase ‘gateway to the Highlands’ is often used in association with Inverness, and the roads that open out from that city take the traveller off and away, to the North, to the West, to the Islands, to the Pentland Sea.

Finally, to add to the complexity of the term ‘Highland’ and its meanings, the Highland Council area, created as one of the local government regions of Scotland, excludes a large area of the southern and eastern Highlands, and the Western Isles, but includes Caithness. Even so, ‘Highlands’ is sometimes used as a name for the council area, as in ‘Highlands and Islands Fire and Rescue Service’, and consists of the Highland Council area and the Island Council areas of Orkney, Shetland and the Western Isles. There is much talk as to the use and relevance of these terms and Highland Council signs at the Pass of Drumochter, between Glen Garry and Dalwhinnie, saying ‘Welcome to the Highlands’ are still regarded as controversial. Nevertheless, it’s fair to say that whenever any of us say ‘I’m off to the Highlands’ we know what we mean. For though there will always be different definitions in different contexts throughout the region, the emotional resonance referred to earlier that sounds from the word ‘Highland’ will always strike a particular note.

Geology

The Scottish Highlands are largely composed of ancient rocks from the Cambrian and Precambrian periods which were uplifted during the later Caledonian land shifts. Smaller formations of Lewisian gneiss in the north-west are up to 3,000 million years old and amongst the oldest found anywhere on earth. These foundations are interspersed with many igneous intrusions of a more recent age, the remnants of which have formed mountain massifs such as the Cairngorms and the Cuillins of Skye. A significant exception to the above are the fossil-bearing beds of Old Red Sandstone found principally along the Moray Firth coast and partially down the Highland Boundary Fault. The Jurassic beds found in isolated locations on Skye and Applecross reflect the complex underlying geology that describes when the entire region was covered by ice sheets during the Pleistocene ice ages. The complex geomorphology includes incised valleys and lochs carved by the action of mountain streams and ice, and a topography of irregularly distributed mountains whose summits have similar heights above sea-level, but whose bases depend upon the amount of denudation to which the plateau has been subjected in various places.

The North East region

Map showing Highland region in relation to the rest of Scotland

i

General information

The area in which ‘The Big Music’ takes place is in the central region of Sutherland, north-west of the coastal villages of Golspie and Brora, and set inland somewhat from the better-known Helmsdale and Naver and Halladale Straths. This is a remote region, not easily accessed by road, even to this day; nevertheless it is served by a rail link that has a ‘request’ stop that is a forty-minute drive or so to The Grey House.

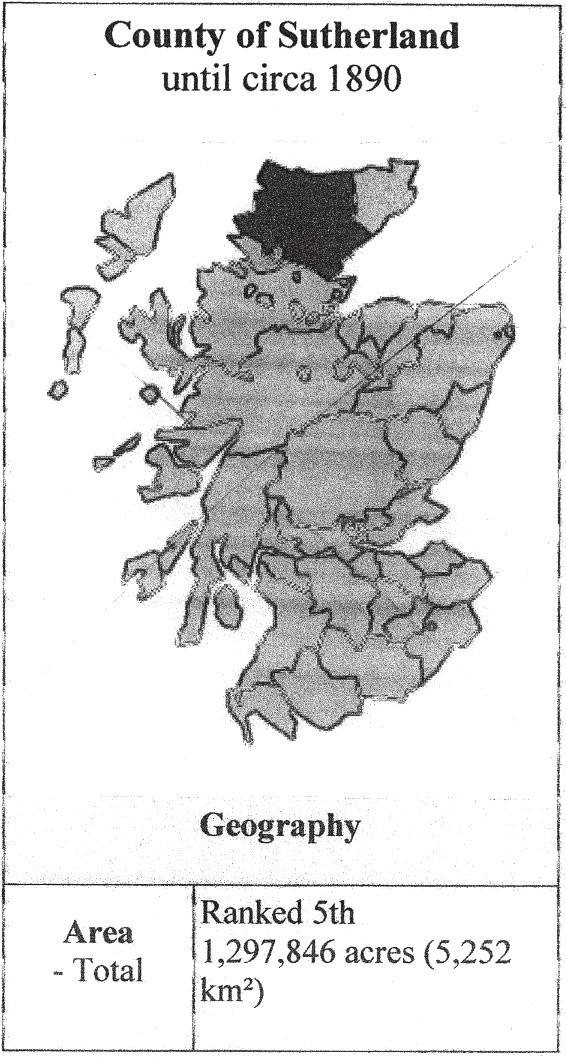

The map here may be of interest, showing an earlier configuration of the county that is described in ‘The Big Music’, its land mass in relation to the rest of Scotland.

Today, Sutherland is within the Highland local government area, the regions of which sit well outwith that represented here and which in Gaelic is referred to according to its traditional areas: Dùthaich ‘Ic Aoidh (NW), Asainte (Assynt) and Cataibh (East). However, Cataibh can often be heard used as referring to the area as a whole.

The county town, and only burgh of the county, is Dornoch. Other settlements include Bonar Bridge, Lairg, Brora, Durness, Embo, Tongue, Golspie, Helmsdale, Lochinver, Scourie and Kinlochbervie. The population of the county as at the most recent census was 13,466.

The name ‘Sutherland’ dates from the era of Norse rule and settlement over much of the Highlands and Islands, which is why, though it contains some of the northernmost land in the island of Great Britain, it was called

Suth-r-Land

(‘southern land’) from the standpoint of Orkney and Caithness and those lands further north.

The north-west corner of the county, traditionally known as the Province of Strathnaver, was not incorporated into Sutherland until 1601. This was the home of

the powerful and warlike Clan MacKay that had connections in those earlier times to the Sutherland family of ‘The Big Music’. Even today this part of the county is known as MacKay Country, and, unlike other areas of Scotland where the names traditionally associated with the area have become diluted, there is still a preponderance of MacKays in the region and nearby, settling further east through marriage, into the interior of Sutherland.

As well as Caithness to the north and east, Sutherland has the North Sea (Moray Firth) coastline in the east, the historic county of Ross and Cromarty to the south, and the Atlantic coastline in the west and north. Like its southern neighbour, Wester Ross, the county has some of the most dramatic scenery in the whole of Europe, and for the purposes of this book it should be noted that the great hills of Mhorvaig and Luath have come to dominate the central strath, the so-called ‘corridor’ through which the sheep were driven in the early nineteenth century and so became the place where the Sutherland family of ‘The Big Music’ established themselves. The emptiness and sense of isolation in this part of Sutherland is acute – more so, even, than in the neighbouring straths of the North East – which no doubt is part of the reason, after a long period of habitation in the area by the same family, the land was initially let over to the first John Roderick MacKay of ‘Grey Longhouse’ as recorded in the Taorluath section of the book, and then subsequently claimed as his own by his son’s son for the family to therefore inherit. Mhorvaig and Luath are the two hills that most dominate this area of the landscape, side by side as they are, set into the hills around them, to the left-hand side of the strath and what is now called The Grey House.

So this part of the world is remote enough. Despite being Scotland’s fifth-largest historic county, it has a smaller population than a medium-size Lowland Scottish town even though it stretches from the Atlantic in the west, up to the Pentland Firth and across to the North Sea. As would be expected, much of the population is based in seaward towns, leaving large swathes of the inner portions of the land utterly uninhabited – or where there are small settlements they are quiet and during the day can scarcely be seen from a distance against the grey-green land and at night lit just enough to show themselves as pinpricks against the endless dark.

And those hills of Mhorvaig and Luath? It’s where this book begins: with these hills and the other hills all around them, sitting as they do against the sky and not changing but for the shapes of clouds upon their sides or the runs of water that flood them in the spring melts or at times of heavy rain. ‘The hills only come back the same’, remember? The first line of this book. As it is also its conclusion.

Comprised of Torridonian sandstone underlain by Lewisian gneiss, the land mass is formed in such a way that the same hills can only be traversed with great difficulty by even the most able walkers and have portions of them still that remain unknown and hidden. This is why the ‘Little Hut’, as it is called in ‘The Big Music’, could

remain unknown; it is why the local walkers’ guide to this area of the Sutherland region notes: ‘Such mountains as these are attractive for hill walking and scrambling, despite their location, for they have a unique structure with great scope for exploration. On the other hand, care is needed when bad weather occurs owing to their isolation and the risks of injury and the fact that so many portions of them seem hidden to the eye until one is upon them or has dropped right down into a formerly unseen crevice or small valley to find an unworn path there that one may never have known existed.’

Transport links in this region are poor: the A9 main east-coast road is challenging in parts and there are few inland roads, the east-coast Far North Line north–south single-track railway line only, and no airports. Much of the former county is poor relative to the rest of Scotland, with few job opportunities beyond government-funded employment and jobs made available on estates or private houses – such as The Grey House of this book that was established as a Piping School from 1835 onwards and took pupils who would board for a time while lessons took place. Later, as its lands were further developed, it would also have employed more keepers and agricultural assistants, in the way Iain Cowie was employed by old (Roderick) John Callum in the early 1960s.