The Big Ratchet: How Humanity Thrives in the Face of Natural Crisis (12 page)

Read The Big Ratchet: How Humanity Thrives in the Face of Natural Crisis Online

Authors: Ruth DeFries

Ancient river civilizations and farmers who slashed and burned forests found ways to stem the catastrophic drain on their soils’ fertility with each harvest. But the pivotal transition to settled life created yet another conundrum in need of a solution. Before the transition, foragers used human energy—in other words, calories from food—to chase

prey; catch fish; gather fruits, seeds, and roots; carry the catch back to camp; and prepare the meal. The energy burned in this work must have been less than the payback in calories

they got from their efforts. It had to be so. With only the brawn of their own human labor, they could not have survived if they had to expend more energy than they consumed. For most of human history, people subsisted by expending less energy in collecting and hunting food than they obtained from eating it.

With farming societies, besides clearing the land, there are other tasks to be done: hoeing, planting, weeding, warding off pests, harvesting, storing, cooking, and moving the food to where people eat it. All of these tasks use energy, if not from human labor, then from another source. When people settle in towns and do specialized, non-farming tasks, they need calories for energy to do the work. A farming family needs to produce not just enough to replenish the amount of calories that they burn themselves; they need to produce extra to feed the people in the towns. One solution to the conundrum of how to get the extra energy was to supplement human labor with the brawn of domestic animals. Animals can do the work from the energy they get eating grass

that people can’t digest. Later on, fossil fuels produced from the energy of the ancient sun took on the same role in the Big Ratchet’s story.

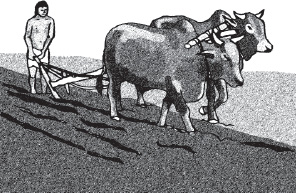

People began to harness animals to pull plows in the early river civilizations around 6,000

or 7,000 years ago. An ox pulling an ard, a rudimentary wooden plow, marked a pivotal transition. The pivot added animal power to humanity’s toolkit. A strong ox could equal the labor of six to eight adult men and plow a field faster than a

person with a hoe. Oxen were supplementing human labor, at a cost of breeding and feeding. So long as oxen could get enough food from grazing, the cost was well worth it. The animals sped up plowing, hauled goods, and later turned waterwheels to mill grains.

Of course, whether people rely on oxen, mules, coal, or petroleum to supplement human labor, any form of energy traces back to the sun,

the starting point for food and all civilization. The sun’s energy powers the entire web of plants, plant-eating animals, animal-eating animals, and on up the chain. It starts with photosynthesis, the amazing process billions of years old that converts the sun’s energy to sugars by breaking apart carbon dioxide from the air and water. Plants use the sugars to grow leaves, stems, and roots. Animals, in turn, get their energy from eating the plants. But much energy gets lost in the process. A common rule of thumb states that about nine out of ten calories that these animals eat are needed for energy to grow, stay warm, move, reproduce, and carry out other such maintenance chores. That leaves only one in ten calories stored in their flesh to pass up the chain. When carnivores eat the plant-eating animals, the process repeats, with another nine out of every ten calories getting lost. Ultimately, this means that only one in one hundred calories has transferred from the plants to the carnivores. That’s why there are typically only four or five layers in the pyramid of plants, herbivores that eat plants, carnivores that eat herbivores, and carnivores that eat carnivores. So much energy gets dissipated at each step that there’s not enough left

after a few transfers. What’s more, unlike nitrogen, phosphorus, and water, usable energy does not recycle. It’s a one-way proposition. The energy lost when a carnivore eats an herbivore is gone forever.

The problem for humanity is not a shortage of energy from sunlight. The problem is getting the sun’s energy into a form that people can eat. There are plenty of plants, but most are too woody or leafy to digest. It’s a lot of work to channel the sun’s energy to the plants and animals that we can eat. It takes a lot of energy. If animals can pull, haul, or otherwise do the hard work instead of farmers, there are even more calories produced for each calorie that the farmer burns. Animals can subsidize the farmer’s labor, enhancing the amount of calories each farmer could produce on the same amount of land with his labor alone. So long as the animals can get enough calories to eat

and are tame enough to do the work, it’s a way out of the energy conundrum. The caloric surplus made ancient cities viable. Animal labor was pushing societies through the bottleneck to convert the sun’s energy into edible form.

Ancient China Sidesteps the Bottlenecks

Ancient Chinese society found ingenious ways around both conundrums of settled life: how to keep soils fertile and how to supplement human labor with more energy. By the beginning of the Common Era, farming had expanded way beyond the floodplains where civilization had taken hold. Land was scarce. Without new territory to clear, the settled Chinese had little choice but to abandon slash-and-burn farming. People had concentrated in cities, magnifying the conundrums of settled life and creating a self-perpetuating cycle between the demands of a growing population and new innovations that enabled it to grow further. The system they ultimately devised led Justus von Liebig to later claim, “The Chinese are the most admirable gardeners and trainers of plants, for each of which they understand how to prepare and apply the best-adapted manure. The agriculture of their country is the

most perfect in the world.”

Liebig’s notion of Chinese agriculture refers to their sophisticated mimicry of the nitrogen and phosphorus cycles to resolve the soil-fertility conundrum. By perhaps 3,000 years ago, the Chinese had figured out that clover, soya beans, and adzuki beans enriched the soil and boosted rice yields. They were calling on the services of

Rhizobium

bacteria that live on the roots of these legumes to break apart the bond in nitrogen gas. The leguminous plants, when plowed under or stored to apply later, helped to keep nitrogen in the soil and millions fed in the growing empire. About a millennium later, Chinese farmers were rotating crops: one season millet or another grain, the next season soya or another legume,

then maybe sesame or some other oil crop. The rotations replenished nitrogen and kept yields high.

The ancient Chinese had another key strategy for feeding large numbers of people. They followed the basic principle of the planetary machinery, recycling nutrients in a continual loop from soil to plants to animals and back to the soil. They used water buffalo, oxen, goats, pigs, and all their other domesticated animals as grand recycling machines. The animals produced manure that was rich in nitrogen, phosphorus, and other nutrients. Microbes took over to recycle the nutrients in manure back into the soil so the crops could grow again. The animals ate the leftovers from the crops in the field. On it went. Collecting the manure and bringing it back to the fields kept the cycle going.

The ancient Chinese didn’t waste even the nutrients in human excrement. Their organized systems for collecting human waste from people living in cities—euphemistically termed “night-soil”—as well as all manner of food scraps and other wastes, were unrivaled. So intently did the Chinese recycle night-soil that Victor Hugo wrote in

Les Misérables

that “not a Chinese peasant goes to town without bringing back with him, at the two extremities of his bamboo pole, two full buckets of what

we designate as filth.” They recycled nutrients from all kinds of sources, dredging sludge from canals, for example, and spreading it on the fields to achieve the same effect as the great rivers that deposited

nutrient-rich soil on the floodplains. Over the centuries they perfected these systems, with different mixtures of waste applied to different crops—ash to legumes and nutrient-rich pig and

human waste to vegetables. Their highly organized social and political systems went hand in hand with the sophistication of their agriculture, as did the complex waterworks they used to bring water to fields. The plains prospered, with

canals to channel water. Bamboo rigs with iron drill bits could reach deep stores of water

thousands of feet below the ground. Farming was not confined to the shores of rivers or ready sources of water.

The highly developed agriculture still could not save the ancient Chinese from the scourges of disease, drought, and famine. One province or another suffered from famine nearly every year.

Untold millions died of starvation. Human excrement that fertilized the fields carried diseases, such as schistosomiasis, known as snail fever for the parasitic worms that hatched in snails, crawled under the skin of a barefoot farmer, laid eggs, and infected the unfortunate victim. Cholera epidemics from water contaminated with human and animal waste

swept through the population.

With dense populations and land and nutrients too scarce to spend on raising animals for slaughter, meat was a rarity in the Chinese diet. As a result, Chinese society circumvented the energy conundrum that compounds when people use animals for meat. With so many calories lost in the transfer up the food chain, the energy cost of meat in the diet is immense, though the gain in protein might be worth the cost. If the cost in calories to feed, butcher, and carry the animals exceeds the payback in calories gained from eating the meat, it’s a losing proposition from the standpoint of energy. The ancient Chinese stayed out of the red by eating plants and animals that didn’t cost more human calories to produce than the payback received from eating the food.

For thousands of years, and despite famines and disease, the Chinese systems of waterworks, waste recycling, and meat-sparse diets supplied enough food to sustain millions of city-folk, not to mention the farmers themselves. While Europeans were living through the Middle Ages, the largest cities in the world were in China: Chang’an in the year 800, Hangzhou in 1200, Nanjing in 1400, and

Beijing in 1500. Cities were surrounded by rings of fertile soil within a day’s journey of the urban

source of night-soil.

Early Chinese civilization was not the only culture to manipulate nutrient cycles to keep its soils fertile, nor the only one to use animal manure to replenish nutrients and animal muscle power to supplement

human labor. In early antiquity, Egyptians were cultivating nitrogen-replenishing clover every other year as fodder for livestock, alternating it with a year of barley or wheat. Wood carvings from Japan depict farmers carrying night-soil to the fields. And in medieval England, so prized were the sheep droppings that the nobles forbade peasants to remove the nutrient-rich manure from a lord’s land. But for many centuries, no society rivaled the Chinese in their mastery of the conundrums of settled life.

It took some centuries before animal power made its way from the ancient river civilizations to Europe. Collar harnesses had originated in China during the fifth century

CE

. Invaders from central Asia might have carried the new type of harness to Europe, where it became

widespread by around 1000

CE

. Unlike harnesses in Roman times, when yokes choked horses pulling heavy loads, animals wearing the new collars had weight distributed across their shoulders. The collars enabled horses, and not just oxen, to pull heavy plows. Because horses worked faster and needed less food than oxen, the energy return in terms of human calories from the harvest increased for each calorie fed to an animal. Iron shoes nailed to horses’ feet, beginning in Europe around the ninth century, protected their hooves from cracking and made the animals even more useful, as they could then work year-round in wet soils. The moldboard plow, another Chinese invention, which cut deeper and in heavier soils, replaced the ard. Donkeys and mules became part of the animal labor pool beyond horses and oxen.

With the moldboard plow in medieval Europe, the fields produced far more for each investment of human labor. The medieval animal-based technology made possible the expansion of agriculture into the wet, clay-rich soils of northern Europe’s forests and wetlands.

Famines were less frequent, and legumes, milk, eggs, and meat were more plentiful in the diet. With animal power to pull and carry heavy loads,

cereal yields nearly doubled. European populations grew and became

concentrated in towns and cities. But this ratchet didn’t last.

In the fourteenth century, the population exceeded the food supply and the hatchet fell. Life was always hard for rural peasants of medieval Europe, as their skeletons in cemeteries attest. Deformed spinal columns, arthritis, and enlarged joints—the payment for carrying heavy sacks and laboring excruciatingly hard to push plows and harvest grain with a scythe—are reminders of the toil the people endured in their short lives. To add to the hardships, midway through the second decade of the fourteenth century, following a century of mild weather, harsh, cold winters arrived, followed by spring downpours that brought catastrophic floods. Crops and pastures were under water, and grain rotted in the fields. The Hundred Years’ War, from 1337 to 1453, was just one of the many conflicts that exacerbated the devastation. Marauding armies drained food from the countryside, and rulers invoked

heavy taxes on the peasants. Famines became frequent throughout northern Europe, killing millions. In one French province, for instance, famine

struck in 1321, 1322, 1332, 1334, 1341,

and 1342. In 1347, infected fleas spread to Europe from Asia and brought bubonic plague to an already weakened population. The Black Death killed a third of Europe’s population and demolished the economy.