The Billionaire Who Wasn't (24 page)

Read The Billionaire Who Wasn't Online

Authors: Conor O'Clery

Around this time, Feeney told Ed Walsh over breakfast at Ashford Castle about Estonia's “heroic efforts” at reform within the Soviet Union. “Would you ever think of going out there, meeting with the rector of the University of Tartu to see if you could help?” he asked. “Chuck so seldom asked and so frequently gave” that he could only agree, said Walsh. He lined up a delegation led by Gus O'Driscoll, the mayor of Limerick, and set off for Estonia, where he signed an agreement with Tartu University on an exchange of studentsâas a result of which his eldest son, Michael, went there to study and met his future wife, Marju. “Now my children and first grandchildren speak Estonian,” said Walsh, “all triggered by Chuck.”

By now, Chuck Feeney's mind was thoroughly bifurcated. The opportunistic way he did business for General Atlantic Group Ltd., acquiring elements here and there, had clearly transferred to his philanthropy. Limerick showed that. If he saw a good opportunity, either to increase the non-negotiable assets of the foundation through doing business deals, or to decrease the liquid assets through acts of giving, he would take it, and leverage it into help for other institutions in an ever-expanding network.

CHAPTER 16

Leaving Money on the Table

By 1986, DFS had become the largest retailer of liquor in the world, selling $250 million worth a year. It was the biggest single retailer in Hong Kong, Hawaii, Alaska, and Guam, and also had retail operations in Singapore, Taiwan, Macau, Saipan, New Zealand, and Australia, and in the United States in Los Angeles, San Francisco, Dallas-Fort Worth, New York, and Boston. It was paying $185 million in fees for forty concessions at twelve international airports. Worldwide, the company employed over 6,500 people, 1,200 in Hawaii alone. It was an international retailing colossus so big that it was a major reason for Japan's $10-billion tourism deficit. Japanese overseas travel continued to enjoy phenomenal growth. From 1964 to 1986, passenger growth had increased on average 19 percent a year and the value of the yen had increased by 4 percent a year.

The days were long gone when DFS was snubbed by the top-brand suppliers as a fly-by-night discount operation. Now it offered premier labels for the designer-conscious Japanese tourists in huge modern stores, though it remained fiercely loyal to those who had stood by it in tough times, and anyone entering DFS shops was confronted with prominent displays of Camus cognacs and Nina Ricci perfumes. What DFS chief executive Bellamy called their “ego-intensive merchandise” included Hermès ties, Gucci shoes,

Tiffany diamonds, Bulgari watches, Dunhill lighters, Montblanc pens, Swarovski crystal, Wedgwood china, and Godiva chocolates. Japanese office ladies crowded around the cash registers to buy Fendi bags and Chanel perfume at less than half the price at home, and Tokyo business executives handed over hundreds of dollars for bottles of vintage Chivas Regal.

Tiffany diamonds, Bulgari watches, Dunhill lighters, Montblanc pens, Swarovski crystal, Wedgwood china, and Godiva chocolates. Japanese office ladies crowded around the cash registers to buy Fendi bags and Chanel perfume at less than half the price at home, and Tokyo business executives handed over hundreds of dollars for bottles of vintage Chivas Regal.

In his annual 1986 report for the eyes of the four owners only, Bellamy wrote that it was a spectacular year, a “special vintage.” They had caught a big wave “and we rode it all the way in.”

“The great department stores are a century old, but we were born with the jet,” enthused Bellamy in an interview published in the

Financial Times

in June 1986, explaining how the company had created an unequaled sales machine to cash in on Japanese consumer culture. In his interview, he explained how DFS had employed shrewd marketing to get Japanese patronage. “In the early days we were purely an operating company, now we are merchants in the fashion business, retailers to the international traveler.”

Financial Times

in June 1986, explaining how the company had created an unequaled sales machine to cash in on Japanese consumer culture. In his interview, he explained how DFS had employed shrewd marketing to get Japanese patronage. “In the early days we were purely an operating company, now we are merchants in the fashion business, retailers to the international traveler.”

When the DFS owners saw the article, their reaction was “explosive,” according to Tony Pilaro. Feeney was agitated. He sent his board representative George Parker “to express his discomfort to me in no uncertain way,” recalled Bellamy. The partners knew that one of the reasons for DFS's success was that its international operations were a mystery to outsiders. No one quite knew how duty free worked or how big DFS was. The owners had been alarmed at an article the same year in the

World Executive Digest

that criticized DFS in Hong Kong for trading on its duty-free franchise to promote other goods as duty freeâthough it gave flattering portraits of the founders: It said that Feeney remained the éminence grise who brought into the operation “all the drive and kinetic energy of a cyclone,” while Miller, “banker, financier, sportsman and

bon vivant

personifies all that is acceptable and respectable of DFS worldwide.”

World Executive Digest

that criticized DFS in Hong Kong for trading on its duty-free franchise to promote other goods as duty freeâthough it gave flattering portraits of the founders: It said that Feeney remained the éminence grise who brought into the operation “all the drive and kinetic energy of a cyclone,” while Miller, “banker, financier, sportsman and

bon vivant

personifies all that is acceptable and respectable of DFS worldwide.”

Above all, the DFS owners wanted to keep secret the amount they were taking out of the company in dividends and their unique tax arrangements. In 1986, it was a staggering $186 million, of which Feeneyâor his foundationâreceived $39 million in cash.

That year the free flow of cash was almost intercepted by Uncle Sam. DFS operated its business activities in the United States and Guam through a Netherlands Antilles holding company, which enabled the four foreign-registered owners to avoid paying tax on the dividends. In 1986, however, the U.S. government planned to eliminate this exemption, and the owners

faced paying tax on future dividends at 30 percent. Under the new regulations the company could also have to pay double U.S. tax on DFS profits.

faced paying tax on future dividends at 30 percent. Under the new regulations the company could also have to pay double U.S. tax on DFS profits.

Pilaro came up with an audacious solution that involved liquidating the Netherlands Antilles company overnight, operating it as a U.S. partnership, and distributing all of its assets to the foreign shareholders. Through a clever revaluation (known as a “step-up”) of the assets, even the one U.S. tax on company profits that they had been paying was largely eliminated, at least for several years. There was a lot of paper shuffling and filings and basically nothing changed, but the scheme resulted in an estimated cash savings of $700 million over the following decade. “In short,” said Pilaro, “the plan turned DFS U.S. operations into a tax-free cash flow machine.”

The “Big Bang” restructuring put more distance among the four founders. They were still regarded by everyone as the owners of DFS, but they were now, in legal terms, “shareholder representatives” of the tax shelters and charitable foundations they created.

This dissonance may have contributed to missteps in the all-important bidding process. The four had stepped down from managing the business, but they kept control of the company, and this meant getting together when the time came to calculate a bid. In 1987, they got it wrong in Hong Kong, their original base. The system in Hong Kong was different from everywhere else. On a given date, bids were dropped into a tender box situated in the lift lobby of Central Government Offices on Lower Albert Road. The four owners would walk up together and drop in the bid and wait to be notified by official letter who had won. Once, they nearly lost it by default, remembering at the last minute that they needed to include two copies and not just one.

After they submitted their tender on June 4, 1987, to renew the three-year liquor and tobacco concession, they found themselves outbid by Kiu Fat Investments Corporation, a consortium of three Chinese companies backed by the People's Republic of China. It was led by former left-wing movie star Fu Chi and his actress wife, Shek Wai, famous for their role in a 1967 real-life political melodrama when they spent twenty-seven hours on a bridge between Hong Kong and China protesting at Hong Kong's attempt to deport them for Cultural Revolution activities. Kiu Fat outbid DFS by more than 25 percent.

Hong Kong was different from Hawaii, however. This need not be a disaster. Duty free still applied only to alcohol and tobacco; DFS was selling watches, pens, apparel, and everything else the tourists might want. Feeney

took the view that it was unethical to try to undermine the Chinese, and that they should be honorable and take their losses while continuing to do retail business like all other Hong Kong stores. Alan Parker agreed. “We just decided we would stay in business,” he said. “The whole issue of duty free in Hong Kong is false. The whole of Hong Kong is duty free except for a tiny little bit of duty on booze, alcohol, and perfume. We had developed this whole thing, Duty Free Shoppers, we used the name [but] we sold every product in the world.”

took the view that it was unethical to try to undermine the Chinese, and that they should be honorable and take their losses while continuing to do retail business like all other Hong Kong stores. Alan Parker agreed. “We just decided we would stay in business,” he said. “The whole issue of duty free in Hong Kong is false. The whole of Hong Kong is duty free except for a tiny little bit of duty on booze, alcohol, and perfume. We had developed this whole thing, Duty Free Shoppers, we used the name [but] we sold every product in the world.”

John Monteiro, who had returned to run the Hong Kong operation after a number of years in Alaska and Hawaii, took the defeat personally, however. The Chinese organization poached 20 percent of his staff, including managers, salesgirls, and supervisors, and set up a downtown store with a sign saying “Official Duty Free.” He resolved to fight to get the liquor and tobacco concession back. The Hong Kong travel agentsâthe crocodilesâtold Monteiro they might have to support the new store, not least because it was backed by the Chinese government that would one day take over the British colony. But Monteiro dropped the price of his duty-paid liquor to 5 percent below that of the new duty-free store, and every time Kiu Fat dropped its price, he dropped his further. The agents remained loyal after all and kept bringing Japanese to DFS rather than the new store. DFS also did everything it could to discourage European designer houses from supplying an operation backed by Red China.

At Kai Tak airport, the Chinese consortium had the monopoly on selling duty-free items for delivery on board the planesâa major convenience for overloaded touristsâbut Monteiro went to his friends in the airlines, and they agreed to belly-load the

duty-paid

liquor and tobacco from DFS stores as unaccompanied baggage to be picked up in Japan. The airport authority tried to stop him, but Anson Chan, secretary for economic services in Hong Kong, who had been a director of the DFS charity board, ruled that it was not illegal.

duty-paid

liquor and tobacco from DFS stores as unaccompanied baggage to be picked up in Japan. The airport authority tried to stop him, but Anson Chan, secretary for economic services in Hong Kong, who had been a director of the DFS charity board, ruled that it was not illegal.

“It was a huge fight, and the Chinese suffered such tremendous financial loss because they had a minimum guarantee to pay the government, and they didn't have the sales,” said Monteiro.

An official from the New China News Agency, which represented the People's Republic of China in Hong Kong, asked to meet Adrian Bellamy for lunch. “He was a very intelligent guy and very impressive,” said Bellamy. “He put a lot of pressure on me and on DFS to stop the fight. He said, âWhen two lions fight, they both get hurt.' It didn't deter us in any way. Johnny Monteiro was the really aggressive one. He didn't like his marbles being taken away.”

Already camera-shy. Chuck Feeney (age thirteen), front row, second from left, at St. Genevieve's graduation, 1944.

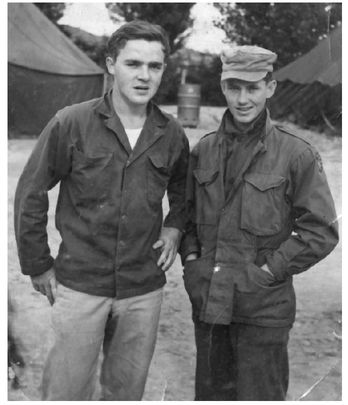

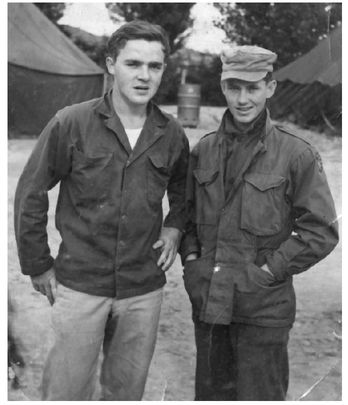

Chuck Feeney (right) with Joe Costello in Japan, September 1951.

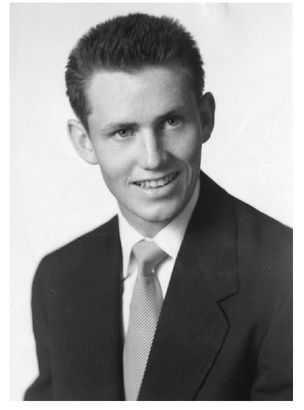

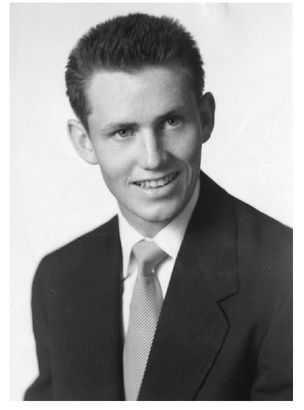

Chuck Feeney, fresh out of the Air Force, 1952.

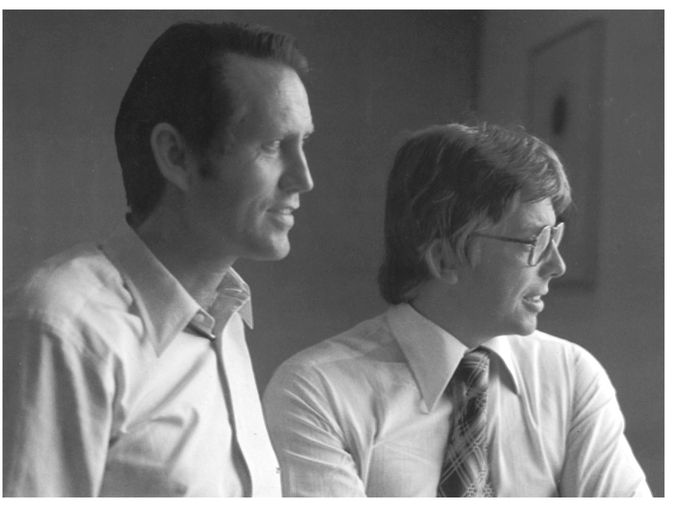

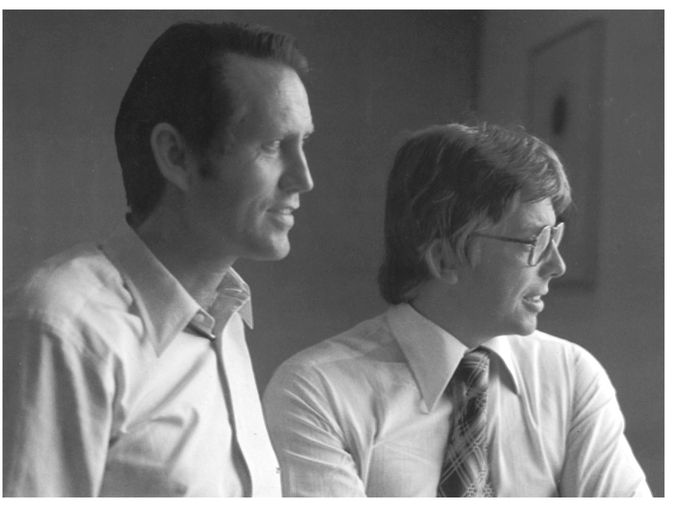

Already well on the way to their first billion, Chuck Feeney (left) and Bob Miller pose for a mid-1970s DFS promotion. The golden partnership would end in acrimony two decades later.

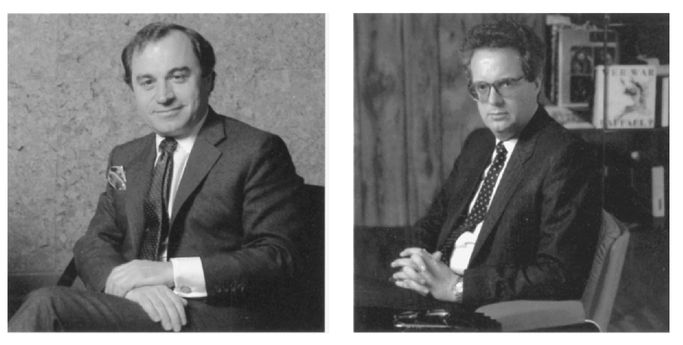

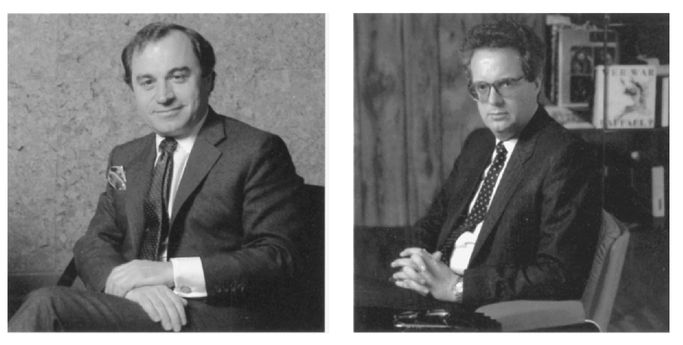

Smallest of the DFS owners with 2.5 percent of the shareholding, Tony Pilaro (left) still made it to the Forbes magazine list of the 400 richest Americans. Lacking the fare to go home to Europe, Alan Parker (right) stayed on in New York as DFS accountant and is today worth several billion dollars. He lives in Switzerland.

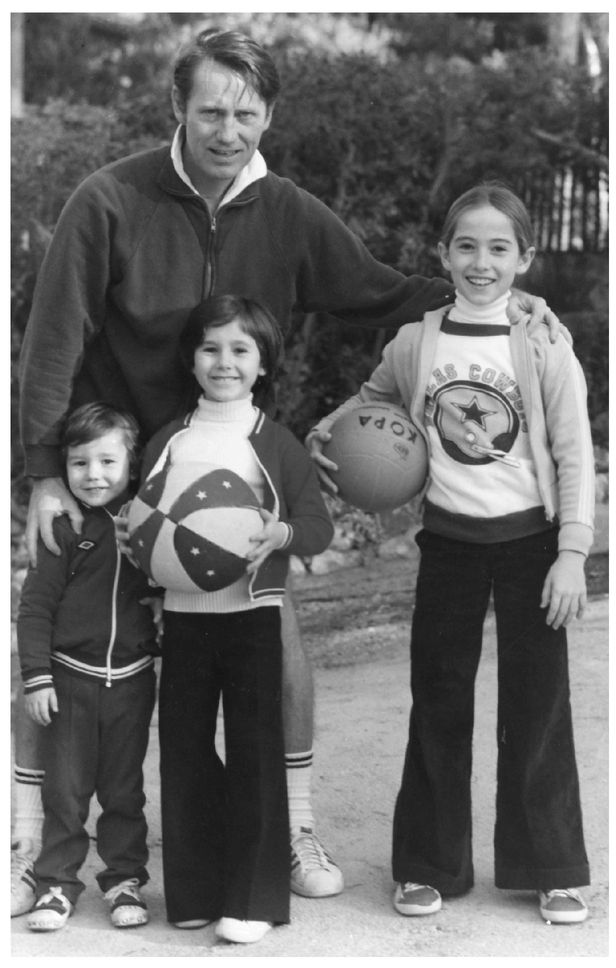

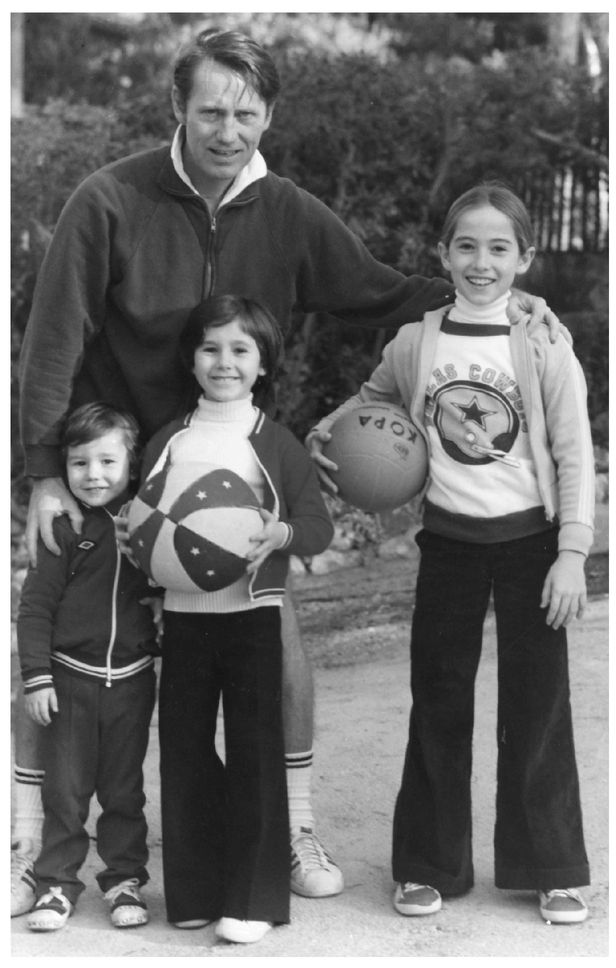

Chuck Feeney with Patrick, Diane, and Leslie.

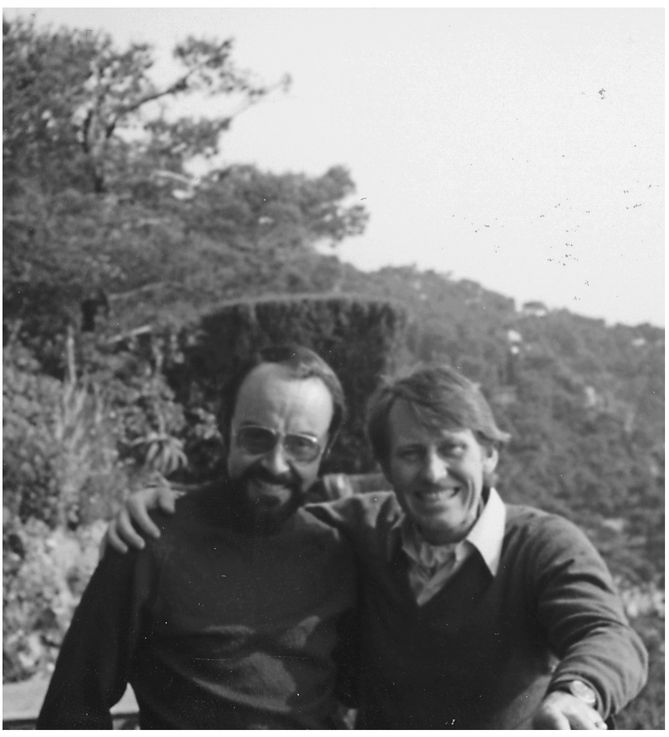

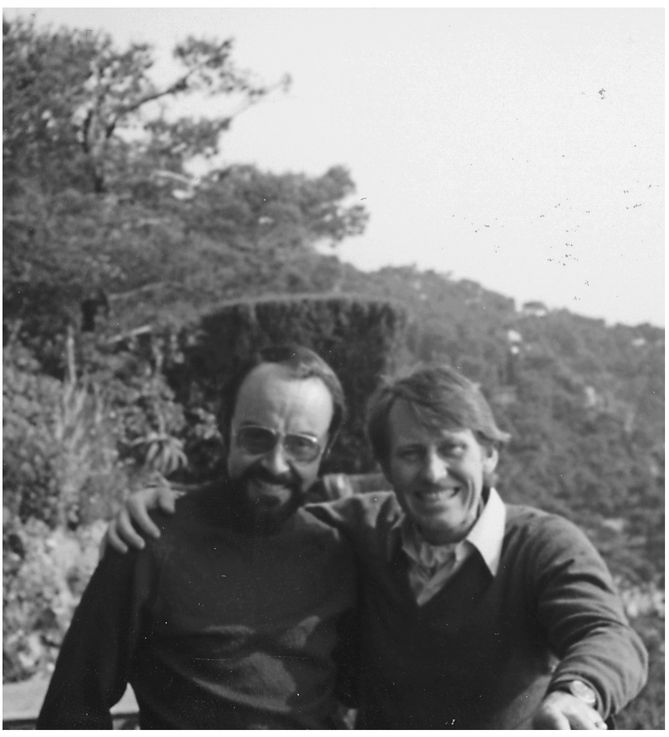

Lifelong friend and colleague Bob Matousek (left), then president of the European Division of DFS, relaxing with Chuck Feeney in the south of France in the summer of 1975.

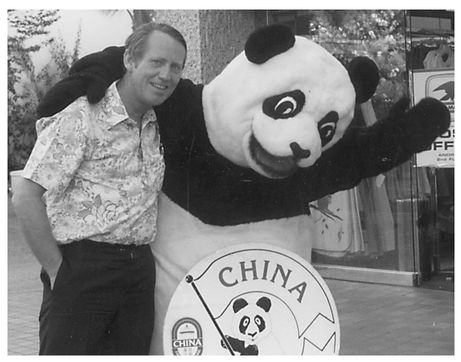

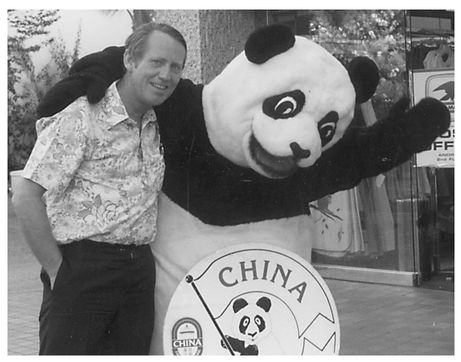

Chuck Feeney with daughter

Caroleen in panda suit,

promoting Chinese products

at the Hawaii store.

Caroleen in panda suit,

promoting Chinese products

at the Hawaii store.

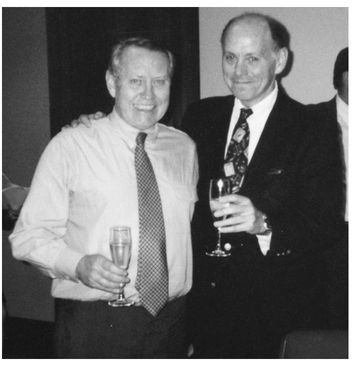

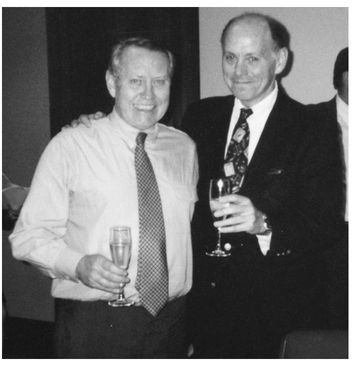

Feeney celebrating the DFS

sale with Harvey Dale.

sale with Harvey Dale.

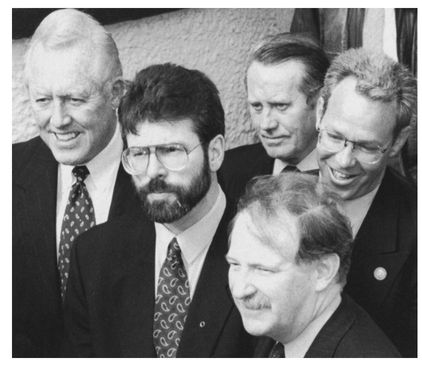

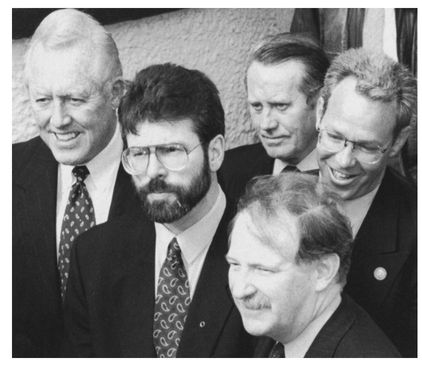

Feeney, in background, failing to

avoid the camera at a meeting in

Belfast in 1994 with Sinn Fein

president Gerry Adams.

avoid the camera at a meeting in

Belfast in 1994 with Sinn Fein

president Gerry Adams.

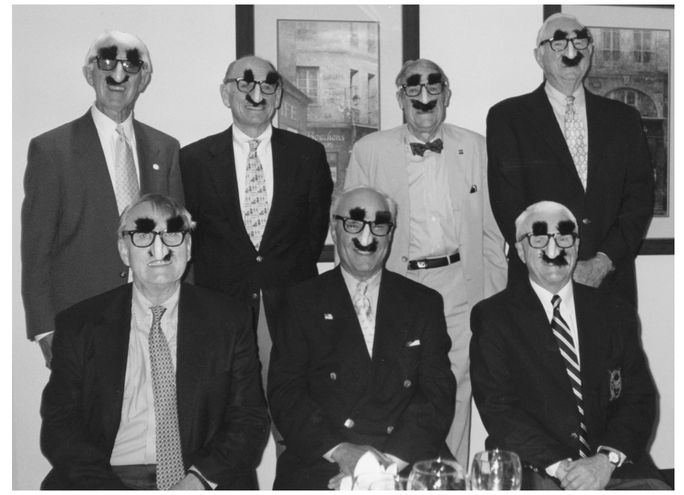

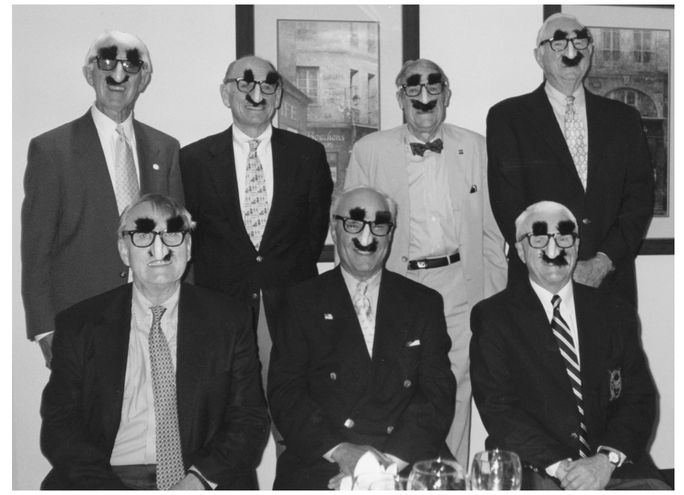

Directors of the Atlantic Foundation advisory board don Groucho Marx masks to mock Harvey Dale's insistence on secrecy. Feeney sits in front row, first left.

Chuck Rolles, Chuck Feeney, Ray Handlan, Fred Eydt, and Bob Gallagher relive their youth at Couran Cove.

Harvey Dale and Chuck

Feeney in a typical

lunchtime setting in

San Francisco.

Feeney in a typical

lunchtime setting in

San Francisco.

Other books

My Lucky Charm by Wolfe, Scarlet

King's Crusade (Seventeen) by Starrling, AD

The Perks of Being a Wallflower by Stephen Chbosky

Perfect Stranger by Kerri M. Patterson

Hugger Mugger by Robert B. Parker

It's Hell To Choose (The Kurtherian Gambit Book 9) by Michael Anderle

Sandra Hill by A Tale of Two Vikings

Brush With Death by E.J. Stevens