The Blood of Heroes: The 13-Day Struggle for the Alamo--and the Sacrifice That Forged a Nation (44 page)

Authors: James Donovan

Tags: #History / Military - General, #History / United States - 19th Century

The reporter obviously talked to or communicated with Johnson, who told him the story of Rose and the line; then he somehow failed to include Travis’s name as “the captain of one of the companies” in his retelling. (The possibility exists that the reporter got the line details directly from Mrs. Hannig—“The child who survives, and is now living in Austin, remembers a circumstance”—but this seems unlikely given the context of the article and the lack of any mention of an interview with her.) Johnson, it is apparent, believed the story after talking to Mrs. Hannig.

Finally, there is this. In the September 9, 1901, edition of the

Gonzales Inquirer

there ran a story entitled “The Fall of the Alamo” detailing an interview with David S. H. Darst, a Gonzales resident “who was one of the participants of the struggle for Texas independence. Darst, a former mayor of Gonzales, and one of the founders of the

Inquirer

in 1851, had called at the

Inquirer

office the previous day to deny certain untrue stories and give the true facts.” (He was also the son of Jacob Darst, one of the “Gonzales 32,” those members of the Gonzales Ranging Company of Mounted Volunteers who had reinforced the Alamo on March 1 and died there five days later. The younger Darst had expressed a desire to go with his father, but had been denied permission.) As related by the reporter:

Mr. Darst was well-acquainted with Mr. and Mrs. Dickinson before the fall of the Alamo and with Mrs. Dickinson after the fall of the Alamo. He also knew the man referred to as a servant called Rose. Mr. Darst says he saw the man Rose in the year 1840. That he was a Frenchman and was in the Alamo before the fall and the Frenchman gave this version: When the Alamo was besieged by the Mexicans and no help near, Travis drew a line and asked all who would stay with him to come over on his side. All crossed over except himself (Rose) and he decided to try and escape during the night. He made his escape by going down the ditch referred to in the above extract [Zuber’s account]. He did not come to Gonzales, the nearest station, but went to east Texas and Mr. Darst did not see him until 1840. This is what Mr. Rose told him.

This article serves as further corroboration of the Rose story by a respected individual, who received it directly from the Frenchman himself.

F

INALLY

, from a larger perspective, Travis’s speech, and the line, make sense. After the arrival of a large Mexican reinforcement on March 3, it must have been increasingly clear that an assault was imminent—and that, despite repeated assurances of Texian reinforcements, none were forthcoming. There are also details that support this knowledge, from Travis giving his ring to Angelina Dickinson and Crockett mentioning his desire to die in his best clothes to the proximity of the Mexican batteries and the knowledge that ladders were being built. And, as Dobie points out, “For Travis to have drawn the line would have been entirely natural…. Travis certainly thought that he was acting a part that the light of centuries to come would illumine.” As is abundantly evident from his actions and his dispatches—and his readings, from Porter’s

The Scottish Chiefs

to Scott’s Waverley novels—he possessed a taste for the romantic and a flair for the eloquently dramatic. The speech and the line would have been entirely in character—and not without precedent in history, from Francisco Pizarro to Ben Milam, who either drew a line in the dirt or asked his men to step across a line or path already there.

As for Moses Rose, he did himself no favors with his story, since he knew others would view his actions as cowardly. It would have made much more sense to either keep his existence in the Alamo quiet or to claim that he had been sent out from the fort as a scout or courier. Instead, he told the truth, and branded himself forever as “the coward of the Alamo”—an unfair legacy for a man who proved his courage many times throughout his life.

T

HERE ARE HISTORIANS

who will complain that much of this evidence is hearsay, or circumstantial, or that post-1873 journalists may have inserted such details into their “interviews,” especially with Mrs. Hannig and Enrique Esparza. They will say that there is no direct evidence that Moses Rose escaped from the Alamo, or that he was even there, or that he was even the same individual, if he ever existed, as the Louis/Lewis Rose abundantly documented in the Nacogdoches records—and that there is even less documentation for the story of the line that Travis drew. Those historians would be technically correct.

But much of what we know as accepted history, as perceived truth—particularly involving events before the advent of recording devices in the late nineteenth century—is derived from similar, or even weaker, sources. Whole swaths of history as we know it derive from similarly limited documentation. Historians have often cited hearsay evidence, though of course after applying tests of bias, objectivity, accuracy, and witness proximity.

An important point to bear in mind is this: there is not a single event associated with the siege and fall of the Alamo that has been related in so many independent versions by so many different individuals attesting to its fundamental truth. Furthermore, not a single one of these people had an ulterior motive, e.g., for money or for personal aggrandizement, in supporting Zuber and his 1873 account. There now exists enough reliable evidence to consider the existence of Moses Rose, his escape from the Alamo, and the line drawn by Travis to be acceptable, factual history.

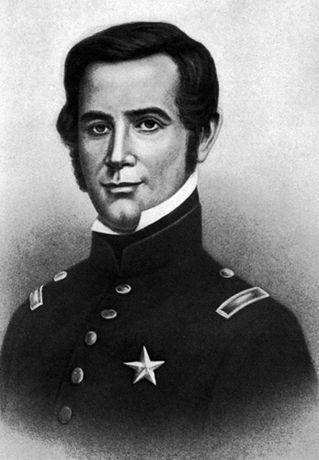

Stephen F. Austin, the first and most successful of the Texas

empresarios.

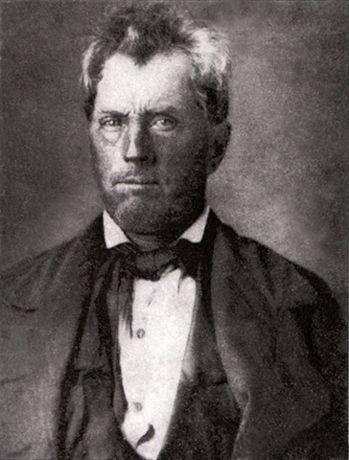

Ben Milam, the Kentucky adventurer and failed

empresario

who rallied the Texian rebels at San Antonio de Béxar.

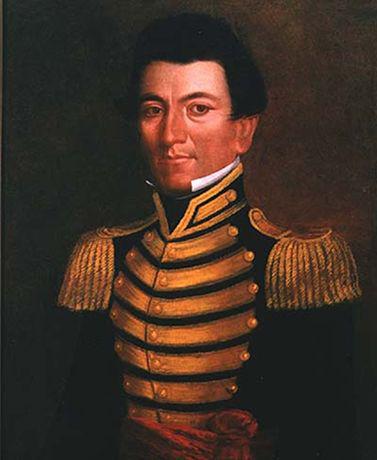

Edward Burleson, Bastrop colonist and seasoned Indian fighter. He was elected commander of the Texian forces surrounding Béxar after Austin’s departure.

Erastus “Deaf” Smith, the legendary scout whom William Travis called “the Bravest of the Brave.”

Juan Seguín, scion of one of Béxar’s most prominent Tejano families. He was a staunch federalist and ally of the Texian rebels.

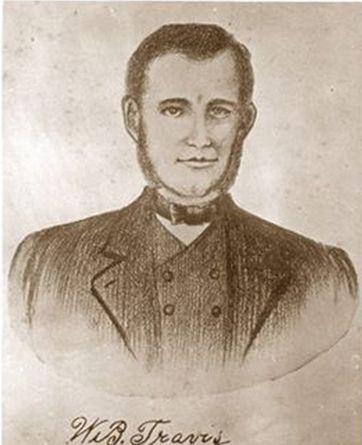

William Barret Travis, in a sketch by Wylie Martin, a San Felipe friend and neighbor. Though the drawing’s attribution is disputed, this is the only known likeness of the Alamo commander.