The Body Economic (7 page)

Authors: David Stuckler Sanjay Basu

Like millions of other Russian men, Vladimir had no hope for the future, no work, nothing to do, and nowhere to goâand

odekolons

were the cheapest way out. About one out of every twelve young Russian men was drinking these noxious alcohols. Only about 5 percent of men who were employed drank them, but nearly 25 percent of those who were unemployed did. These data alone couldn't tell us if the alcohol abuse caused the unemployment or the other way around, but the outcome was devastating either way; the combination of heavy drinking (

zapoi

) and

odekolons

was staggering. In Izhevsk, almost half of all deaths of working-age men were found to be attributable to hazardous drinking (when counting binge drinking and the harms from the surrogate alcohols). Across Russia, alcohol was estimated to have accounted for at least two out of every five deaths among Russian working-age men during the 1990s, totaling 4 million deaths across the former Soviet Union.

16

To understand the full impact of this phenomenon, we looked at data from the Russian Longitudinal Monitoring Survey, which had followed men and their families from 1994 through 2006. Using a technique called survival analysis, we looked at 6,586 men who had jobs in 1994, of whom 593 had died and the rest had survived. We then evaluated what factors could predict who was most likely to have died or survived. The data revealed that the men most likely to drink vodka and nontraditional alcohols were manual workers and technicians. And they were also the most likely men to die. The gap in death rates between the factory workers and the managers had widened dramatically in the period we studied. In particular, the survey asked people about their perceptions of social standing as a measure of social stress. We found that those persons who had the least economic status, power, and respect in their communities were at a three-times greater risk of dying than those with the highest wealth, respect, and power. Overall, we found that a twenty-one-year-old Russian factory worker could expect to live fifty-six years, about fifteen years less than the factory managers and professionals.

17

But the worst risks were seen in people like Vladimir, who were no longer in the workforce; men like him had a six-fold higher risk of dying than those who kept working. As if losing work was not enough of a shock to people's health, in the Soviet Union it also meant the ancillary loss of community and social support structures. In the Soviet era, employment was more than a

paycheck and a purpose in life. Soviet working conditions were quite unlike those in Western firms. Although they were totalitarian and assembly-line-driven, they also had some uniquely beneficial aspects. Soviet planners provided their employees with on-site hospitals, diabetes screenings, childcare, and other social protection programs. While parents worked, children could play. And for the parents, there wasn't too much intensive work happening. The running joke among factory workers was, “We pretend to work, and they pretend to pay us,” and it was true; people didn't earn much, but they did have stable jobs and many fringe benefits. All of these social support programs were provided free of charge to Soviet workers and their families. In the Soviet mono-towns, there was a deep sense of community, as people were, whether they liked it or not, all in it together.

18

A key question, given the troubling rise in deaths, is how these harms could have been avoided. Many have argued that the extraordinary mortality rates in post-Soviet Russia were simply an unavoidable consequence of the necessary shift from a communist to a capitalist economy. After we published our studies showing a rising death rate among newly unemployed Russian men, one analyst for the

New York Times

asked us whether the mortality crisis wasn't “just an unforeseen and unwelcome result of the end of communism.” In other words, was it inevitable that the transition from communism to capitalism resulted in terrible shocks and traumatic risks to health? That's a hugely important question. For answers, we looked at similar data across all the countries that had once constituted the Soviet Union and the Soviet bloc. If stress-related deaths were indeed an

inevitable

result of profound changes inherent to the transition from communism to capitalism, then the data would show dramatic increases in illness and death throughout all these nations.

19

But the data didn't show a rise in deaths everywhere. Poland actually became healthier while Russia got sicker. Both Russia and Poland had experienced similar death rates in 1991, before the fall of the Soviet Union. But three years later, deaths had risen in Russia by 35 percent, while in Poland they fell by 10 percent. Kazakhstan, Latvia, and Estonia all had large jumps in mortality rates on par with Russia's experience, while Belarus, Slovenia, and the Czech Republic did not.

The key to understanding these differences is the policy choices made about how to transition from communism to capitalism. The critical decision was about the appropriate pace of reform. Those countries pursuing a very

rapid transition from communism to market systems with radical privatization programs experienced a one-two punch of mass economic dislocation, together with huge cuts to social welfare. Ultimately the “rapid privatizers” suffered worse health than the “gradualists,” who reformed more slowly and in so doing maintained their social protection systems and saw health improvements during the transition to capitalism.

As the Soviet Union was breaking apart, politicians and economistsâboth in Russia and in the Westâdebated about the best way to establish Western market capitalism on the ruins of communism. It was clear that the Soviet system was unviable, as could be plainly seen in the empty grocery stores and shortages of meat, milk, and matches. Some form of transition needed to occurâand indeed a gradualist one had already begun with Gorbachev's perestroika and glasnost reforms in the late 1980s. As the Soviet Union fell apart, the key question for debate was howâand how quickly.

Economists were divided about what was the appropriate pace of reform. One group of radical free-market advisers argued that the capitalist transition needed to occur as rapidly as possible. These economists pushed for Shock Therapy, a radical package of market reforms. Its proponents were mainly Harvard economists, including Andrei Shleifer, Stanley Fischer, Lawrence Summers, and Jeffrey Sachs, as well as Russian leaders such the Soviet economist and acting prime minister of Russia, Yegor Gaidar.

The rapid reformers argued that the sooner market reforms were implemented, the sooner economic benefits would accrue. That is, the Soviet factories would restructure and be successful again, and people would be more productive and earn more money, lifting Soviet society out of stagnation. Communism's fall had created a period of “extraordinary politics,” according to members of the World Bank's transition economics team, during which politicians could demand great sacrifices from the population. Fast reforms would be economically painful because they would involve cutting people off from all the social protection systems they had been getting; but the reformers were, above all, concerned that if they did not act swiftly, Communists would return to power. This strategy traded short-term pain for long-term gain. This was, in essence, a deeply political plan to prevent the return of Communism and ensure that a capitalist market economy would endure in Russia. Once the market was established in the Soviet state system, it would be all but impossible to reverse.

20

A key supporter of this theory, Jeffrey Sachs, published a landmark paper outlining his plan in January 1990. The essay, “What Is to Be Done,” shared the title of Vladimir Lenin's pamphlet from ninety years prior, which had set out plans for the October 1917 revolution and the creation of Communism. The modern version argued a plan for Shock Therapy, a program to implement rapidly a combination of radical free-market reforms.

21

Shock Therapy had two main elements. First, there would be economic “liberalization,” which meant releasing the government's grip over the prices of goods in the market. The Soviet Union had controlled everything, from the wages workers earned, to the price of bread they bought in the factory towns. Such control needed to end, went the thinking of the Shock Therapists, if the market was to begin to work for the betterment of Soviet society.

22

Next would come a massive privatization program. It would help remove the government's influence and create incentives for profit; extensive privatization would need to take place, selling off government-run projects. This was the most controversial and painful policy, but many economists viewed it as the key. Milton Friedman, the radical free-market economist and godfather of Shock Therapy, put it succinctly: “privatize, privatize, privatize”âbreak the Soviet state's grip on the economy as soon as possible. It was not only the economy that would be affected, however. In the Soviet Union, the state's funds for supporting public health and social services came directly from its state-owned enterprises. Mass privatization would not only dislocate workers, but also lead to huge cuts to its cradle-to-grave social protection system.

23

Never before had anyone attempted to privatize an entire economy in such a short period of time. To put the Shock Therapists' plan into perspective, Margaret Thatcher, the great privatizer of the British economy, privatized about twenty large British utilities companies in eleven years during her time as prime minister. The Harvard economists planned to privatize more than 200,000 Soviet enterprises in less than 500 days. The reformers argued that speed was essential lest the former Soviet Union slip back into communism. As Lawrence Summers of Harvard University put it, “Despite economists' reputation for never being able to agree on anything, there is a striking degree of unanimity in the advice that has been provided to the nations of Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union (FSU).”

24

Yet in reality not everyone agreed with the Shock Therapists. A group of “gradualists,” most prominently Joseph Stiglitz, who had been chief economist of the World Bank and in 2001 would win the Nobel Prize in Economics, concluded that capitalism could not be created overnight. Arguing that it had taken centuries for capitalism to develop in Western Europe, Stiglitz and his allies called for a slower transition, recommending that Eastern European countries slowly phase in markets and private property while allowing regulatory agencies and legal rules time to develop, to ensure that markets worked well rather than becoming manipulated by the powerful. They advocated a “dual-track” system so that former communist countries would incrementally “grow out of the plan,” with the private sector eventually outgrowing an outmoded state-owned sector.

25

As a solution to the debate, in 1991, Harvard economists proposed an idea for a grand bargain, backed by the US government. This promised as much as $60 billion in economic aid to support the Soviet workers and their families if the rapid reform plan was adopted; in exchange, the West would gain military concessions and influence over Soviet foreign policy. The US Agency for International Development led the aid effort, providing nearly $1 billion alone to the region to promote private-sector development. Soviet President Gorbachev, however, called for a slower pace of reform. His political adversary, Boris Yeltsin, approved of the US plan. After an August 1991 military coup against Gorbachev failed largely because of Yeltsin's opposition to it, Gorbachev's power and that of the Soviet Union itself were fatally compromised. Yeltsin banned the Soviet Communist Party in November, and on December 25, 1991, the Soviet Union came to an end.

26

That political outcome tilted the balance of power in Russia to those who supported pursuing Shock Therapy, in a move away from Gorbachev's slower pace of reform. Not just Russia, but most countries in the former Soviet bloc, heeded the advice of the Shock Therapists. Shock Therapy policies were fully implemented in Russia by 1994, as well as in ex-Soviet republics like Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. But politicians in other countries such as Belarus decided instead to take the gradualist path instead of Shock Therapy. A group of relatively similar countries embarked on widely different reform pathsâa huge “natural experiment” in which relatively similar groups of people underwent vastly different reforms, and experienced dramatically different outcomes.

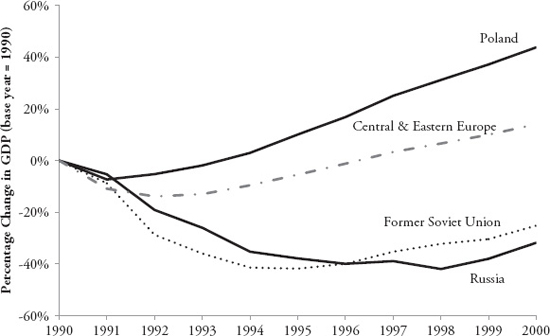

F

IGURE 2.2

Economic Collapse in Russia and the Former Soviet Union, but Rapid Recovery in Central and Eastern Europe

27

The results were disastrous in those countries that implemented Shock Therapy. As shown in

Figure 2.2

, between 1990 and 1996, per-capita income in Russia and most of the former Soviet Union (FSU) plummeted by over 30 percent, slightly less than the decline in the Great Depression. In purchasing-power-parity, Russia's economy in the mid-1990s fell to become equivalent to that of the United States in 1897.

28