The Bondwoman's Narrative (6 page)

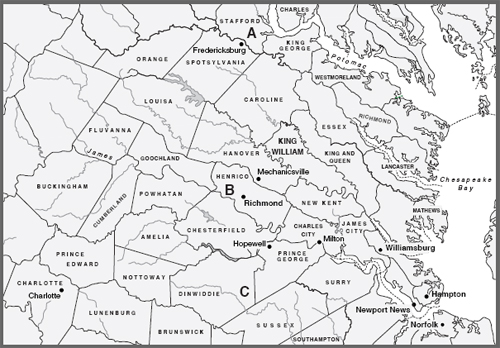

Tracing the locations of key characters.

| J OHN C OSGROVE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . B |

| T HOMAS C OSGROVE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . B |

| F REDERICK H AWKINS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . C |

| R EV . J OHN H. H ENRY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . A |

| E DWARD J OHNSON . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . B |

| E LISA V INCENT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . C |

| N ATHAN V INCENT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . C |

| W ILLIAM V INCENT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . B |

I wrote above that I had been pursuing Hannah Crafts along two parallel research paths. While I awaited the scientific analysis

of the manuscript itself, I was gathering raw data from a variety of archives and sources. If Hannah Crafts had drawn upon

her own experiences as a slave in Virginia and North Carolina as the basis of the events depicted in her novel, then sooner

or later these two paths of research would have to overlap, or mirror each other, in their findings. Despite this expectation,

nothing prepared me for the fascinating manner in which this mirroring would occur.

Joe Nickell had suggested near the end of his report that he felt that “the novel may be based on actual experiences.” Why

did he think this possible? Because of Crafts’s peculiar handling of two of the characters’ names:

There are changes that may be due to fictionalization of real persons or events, such as the change of “Charlotte” to “Susan”

[pp. 46 and 47]. More telling, perhaps, is the fact that the name “Wheeler” in the narrative was first written cryptically,

for example as “Mr. Wh——r” and “Mrs. Wh——r,” but then later was overwritten with the missing “eele” in each case to complete

the name [pp. 148–152).

20

What these manuscript changes imply is that Hannah Crafts most probably knew the Wheelers and that Wheeler was their actual

name. Even more surprising is the fact that she has disguised their name initially, and then filled it in later, suggesting

that the reasons she had wanted to veil their identity no longer obtained when she decided to fill in their names. Moreover,

it is clear that she wanted to leave no doubt about the Wheelers’ historical identity, about who they actually were.

When I read this paragraph in Nickell’s report, I thought of Dorothy Porter’s note to Emily Driscoll, pointing out that one

John Hill Wheeler had held several government positions in the 1850s. Little did I know how important these clues would turn

out to be.

I have no idea how Dorothy Porter identified John Hill Wheeler as a possible candidate for the Mr. Wheeler in

The Bondwoman’s Narrative

. But she was correct. A painstaking search of federal census records for North Carolina and Washington, D.C., revealed that

only one Wheeler in the entire United States lived in both North Carolina and Washington between 1850 and 1880. Every scholar

embarked upon a search of this sort lives for a moment such as this. Not only had Wheeler served in a variety of governmental

positions, he was also a slaveholder and an ardent and passionate defender of slavery, just as Crafts depicts him. But even

more remarkably, John Hill Wheeler in 1855 became for a month or so perhaps the most famous slaveholder in the whole of America,

and all because of an escaped female slave.

By this time, I had decided to share the manuscript with a few other scholars, namely William L. Andrews, Nina Baym, Rudolph

Byrd, Ann Fabian, Frances Smith Foster, Nellie Y. McKay, Augusta Rohrbach, and Jean Fagan Yellin. The generous, encouraging

but rigorous, and sobering responses of these other scholars of nineteenth-century American literature would be important to me as I struggled to gain my bearings in the choppy sea of raw

research that my searches through various archives were producing.

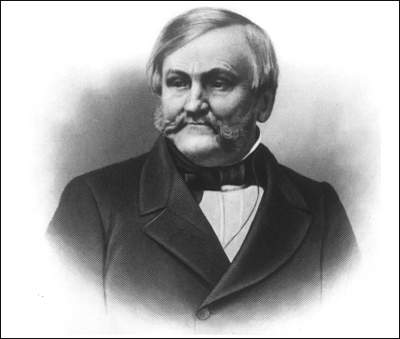

John Hill Wheeler.

(North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina Library at Chapel Hill)

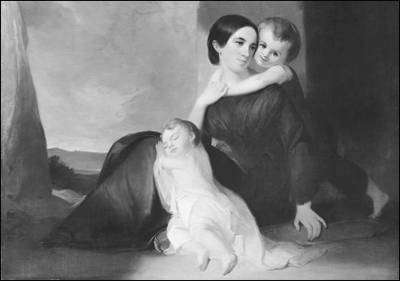

“Mrs. John Hill Wheeler (Ellen) and Her Two Sons”

by Thomas Sully. (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Capt. John R. Brasel, U.S.N.R., 1967)

One day William Andrews phoned to ask if I realized who Wheeler was. I told him what I had learned so far from several biographical

entries, including that in the on-line

American National Biography

database, the most authoritative such listing of American lives yet compiled. In his searches, he replied, he had learned

that John Hill Wheeler not only had been a slaveholder but was the petitioner in the infamous

Case of Passmore Williamson,

a fact that none of Wheeler’s biographers had thought to mention. This case was one of the first challenges to the notorious

Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, and it turned on Wheeler’s attempt to regain his fugitive slave, Jane Johnson. This single observation

would turn out to be the most important clue in establishing crucial details about Hannah Crafts’s life as a slave.

John Hill Wheeler was born in Murfreesboro, North Carolina, in 1806, the son of John Wheeler (1771–1832), the postmaster of

Murfreesboro, and Maria Elizabeth Jordan (1776–1810). He died in Washington, D.C., in 1882. Wheeler graduated from Columbian

College of Washington, D.C. (now George Washington University) in 1826, then studied law under John L. Taylor, the chief justice

of the North Carolina Supreme Court. In 1828 he received an A.M. degree from the University of North Carolina, a year after

he was admitted to the bar. Between 1827 and 1852, he served for various periods in the North Carolina House of Commons, first

between 1827 and 1830. From 1837 to 1841, he served as the superintendent of the branch mint of the United States at Charlotte.

In 1832 Wheeler became the secretary of the French Spoilations Claims Commission. He served as state treasurer between 1842

and 1844.

In 1851 Wheeler published

Historical Sketches of North Carolina from 1584 to 1851,

then returned to the state legislature between 1852 and 1853. In 1854 he was named U.S. minister to Nicaragua, where he served

until 1857, when he was forced to resign for contravening the instructions of Secretary of State William L. Marcy concerning

the recognition of a new government. According to the historian Robert E. May, “Wheeler was minister at the time that the

American ‘filibusterer’ William Walker conquered Nicaragua. Walker eventually reestablished slavery in Nicaragua, in a bid

to get southern support for his regime. Wheeler was extremely supportive of Walker’s reestablishment of slavery, and earlier

recognized Walker’s regime prematurely, to the displeasure of the State Department.

21

He returned to Washington in 1857, visiting North Carolina several times before the Civil War began. Between 1859 and 1861,

he worked in the statistical bureau. He returned to North Carolina during the Civil War, undertook research in England for

a second edition of his history of North Carolina between 1863 and 1865, and returned to Washington in 1865. Wheeler also

published

A Legislative Manual of North Carolina

(1874) and

Reminiscences and Memoirs of North Carolina and Eminent North Carolinians

(1884). He edited Colonel David Fanning’s

Autobiography

(1861), and he left a diary, a Spanish edition of which

(Diario de John Hill Wheeler)

was published in 1974. Wheeler ran for Congress in 1830 but was defeated. He was married twice, first to Mary Elizabeth Brown

between 1830 and 1836, and then after her death to Ellen Oldmixon Sully, whom he married in 1838. He had five children, three

in his first marriage, two in his second.

22

In 1842 Wheeler moved from Hertford County to Lincolnton in Lincoln County, where he ran a plantation. According to the

Dictionary of American Biography

(1999), Wheeler not only was “a plantation owner,” he was also a “staunch advocate of slavery, and firm believer in America’s

manifest destiny to annex parts of Central America and the Caribbean.” In fact, in 1831 Wheeler’s brother raised a volunteer

company from Hertford County that participated in the suppression of the famous Nat Turner rebellion in Virginia.

23

Wheeler was quite passionate not only about defending his own right to own slaves but also about defending and protecting

the entire system of slavery.

According to the 1850 North Carolina census, Wheeler owned twenty-five slaves, ranging in age from one year to fifty. Fifteen

were males and ten were females. Four of the female slaves were between the ages of twenty-one and twenty-five; one was twenty-one,

while three were twenty- five. Could one of these four women have escaped to freedom in the North, and then, as Frederick

Douglass and Harriet Jacobs had done, turned her pen against her master? I began to research Wheeler’s role in

The Case of Pass-more Williamson

in search of possible clues for Hannah Crafts, growing increasingly curious about this Jane Johnson.

The case of Passmore Williamson—or, more properly, the case of Jane Johnson—became a cause célèbre in Philadelphia in 1855.

According to a pamphlet published by the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society in that year, and according to the black abolitionist

William Still, who wrote about Jane Johnson’s escape in his book,

The Underground Railroad

(1872), John Hill Wheeler arrived in Philadelphia on Wednesday, July 18, 1855, on his way from Washington, D.C., to Nicaragua,

to take up his position as “the accredited Minister of the United States to Nicaragua.”

24

Traveling with Wheeler were Jane Johnson, whom he had purchased in 1853 in Richmond, and her two sons, one six or seven,

the other eleven or twelve.

When the foursome arrived in Philadelphia, Wheeler took them to Bloodgood’s Hotel, located near the Walnut Street wharf. When

Wheeler went to dinner in another part of the hotel, Johnson “spoke to a colored woman who was passing, and told her that

she was a slave, and to a colored man she said the same thing, afterwards adding, that she wished to be free.” William Still,

chairman of the Acting Vigilant Committee of the Philadelphia Branch of the Underground Railroad, wrote in a letter published

in the

New York Tribune

on July 30, 1855, that he was handed a note at 4:30 in the afternoon “by a colored boy whom I had never before seen, to my

recollection.” The note read as follows: