The Book of Basketball (86 page)

Read The Book of Basketball Online

Authors: Bill Simmons

Tags: #General, #History, #Sports & Recreation, #Sports, #Basketball - Professional, #Basketball, #National Basketball Association, #Basketball - United States, #Basketball - General

Fatal flaw.

The deer-in-the-headlights routine in big games for Malone. Time and time again, he came up short when it mattered (Game 1 of the ’97 Finals and Game 6 of the ’98 Finals were the best examples), and it’s impossible to forget NBC’s Bill Walton just ripping him apart during that ’97 Finals and repeatedly asking in a cracking voice, “What has happened to Karl Maloooooooone?” But you know what? I can forgive that. Plenty of great players didn’t totally have “it” inside them. Here’s what can’t be forgiven: Barkley’s refusal to stop partying or get himself into reasonable shape; his career should have been 15 percent better than it was.

55

When Pippen lobbed shots at Barkley’s lack of conditioning after their unhappy ’99 marriage, Ron Harper defended Scottie by saying, “Everybody knows Charles is a great guy, but every year he’s talking about winning a championship, and then he comes to training camp out of shape. That shows what kind of guy he is. Pip wants to win. If you aren’t doing what you should be doing, he’s going to let you know.” Ouch. Barkley got himself in shape for those first two Phoenix seasons and that’s it.

56

Malone stayed in superb shape for two solid decades.

Major edge: Malone.

Personality/charisma.

Barkley wins over Malone and everyone else in league history. Who would have been a more fun teammate than Charles Barkley? He loved gambling, drinking, eating, and busting on everyone’s balls. (Wait, that sounds like me!) As for Malone, he was fun to hang out with if you wanted to herd some cattle or needed a workout partner at 7:00 a.m. Um, I’ll take Chuck. And you wonder why he never reached his potential.

Major edge: Barkley.

Head to head.

They only met twice in the playoffs: 1997 and 1998 (with Utah winning both times), but Barkley was injured in ’98 and only played 4 games (87 minutes in all), while the tight ’97 series was swung by the obscenely lopsided Stockton-Maloney matchup. In ’97, Malone averaged 22 points and 11.5 rebounds and shot 45 percent (56 for 125); Barkley went for 17.2 points and 11.0 rebounds and shot 42 percent (27 for 63). Not exactly Hagler-Hearns. When they were playing for quality teams in their primes (’93 and ’94), they met in the regular season seven times: the Suns won five, with Barkley averaging 23.4 points, 11.4 rebounds and 4.3 assists and Malone averaging 21.8 points, 8 rebounds and 3.4 assists. Edge to Barkley. And then there’s this one: Heading into

the ’92 Olympics, many thought the Dream Team would be Malone’s breakthrough. Jack McCallum even wrote, “Many observers think that [Malone and Pippen] will benefit the most from the worldwide exposure, since both are extremely photogenic athletes who, as Malone puts it, ‘haven’t exactly been plastered all over everything.’” So what happened? Barkley emerged as the Dream Team’s second-best player, number one power forward and breakout star. That has to count for

something

, right? Chuck blended in with great teammates better than Malone did, led the team in scoring and became its dominant personality. It’s just a fact. By the end of the Olympics,

SI

was describing him as the “talk of the Olympic games,” with McCallum gushing, “His astonishing range of abilities—outrebounding much taller players, running the floor like a guard and getting his shot off with either hand while bouncing off bodies around the basket—seem more pronounced when performed within the Dream Team galaxy.”

57

What happened to Malone? He sank into the shadows as a supporting player (like one of those

SNL

cast members who appears in the opening credits after the main cast with one of those “and featuring Karl Ma lone …” graphics), getting press only after he raised a fuss about competing against an HIV-positive Magic before the ’93 season.

58

Then Barkley carried Phoenix to 62 wins and gave the Bulls everything they could handle in the ’93 Finals. After the ’93 season, the Barkley-Malone argument was dead; Barkley had won. After the ’94 season? Still dead. Then Malone kept chugging along and chugging along, Barkley let himself go and things began to shift. Barkley’s apex was definitely better, but not

so

much better that it outweighed Malone’s longevity and consistency. Malone maximized the potential of his career; Barkley can’t say the same. It’s true.

Final edge: Malone (barely).

17. BOB PETTIT

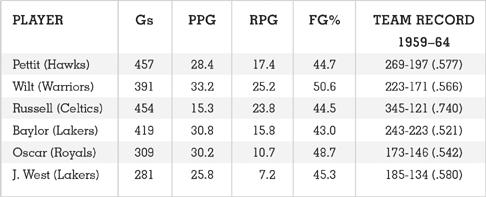

Resume: 11 years, 10 quality, 11 All-Stars … MVP: ’56, ’59 … Runner-up: ’57, ’61 … Top 5 (’55–’64), Top 10 (’65) … ’55 Rookie of the Year … 4 All-Star MVPs … 3-year peak: 28–18–3 … leader: scoring (2x), rebounds (1x) … career: 26.4 PPG (6th), 16.2 RPG (3rd) … Playoffs: 26–15–3 (88 G) … best player on one champ (’58 Hawks) and 3 runners-up (’57, ’60, ’61) … first member of 20K-10K Club

I’m asking for a little leap of faith, like when you watched

The Hangover

and never questioned how the boys could have done so many different things in Vegas during one ten-hour blackout.

59

Could Pettit hang with guys like Duncan and Bosh today? Probably not. Offensively, I think he’d be okay—a less athletic cross between Carlos Boozer and Paul Pierce. (Pettit had three go-to moves: a don’t-leave-me-alone 18-footer, a leaning jumper coming off screens and a reliable turnaround that Bob Ryan once called “monotonous.” He couldn’t dunk unless a donut and coffee were involved. Tom Heinsohn once described Pettit’s cagey offensive game by calling him “the master of the half-inch.” Mrs. Pettit had no comment.) Defensively, you wouldn’t be able to hide him. But everyone from that era describes Pettit the same way:

Relentless. Banger. Warrior. Hard-nosed.

Remember Boston’s more physical playoff games when Bird couldn’t get his outside shot going, so he’d switch gears and start banging bodies down low (eventually pulling down 18 boards and getting to the line 12 times)? That was Pettit. In 64 playoff games in his prime (’57 to ’63), he averaged 28 points, 16 rebounds and a whopping 11.7 free throw attempts.

60

He also exhibited remarkable durability, playing 746 of a possible 754 games (including Playoffs) without the help of chartered planes, arthroscopic surgeons, stretching routines and strength/conditioning coaches. And you can’t play the “Pettit only

thrived because the black guys weren’t around yet” card because nine of Pettit’s eleven seasons coincided with Russell, seven with Elgin, six with Wilt, and five with Oscar and West, even capturing the ’62 All-Star MVP by scoring 25 points and notching a game-high 27 rebounds. Check out these numbers from ’59 to ’64.

Beyond that, Pettit and Wilt were the only two alpha dogs to topple Russell’s Celtics. Pettit avoided a Game 7 in Boston with a then-record 50 points, including 18 of St. Louis’s last 21, as well as a jumper and a clinching tip in the final 20 seconds to seal the 1958 title. So what if Russell was limping around in a cast and only played 20 minutes? That’s still one of the better performances in Finals history.

61

Pettit hasn’t endured historically partly because no tape exists of that game, and partly because he didn’t have that one “thing” that kept him relevant along the lines of Oscar averaging a triple double, Russell winning eleven titles in thirteen years or even West becoming the NBA’s logo. He just missed the television era, didn’t play in a big market and lacked an identifiably transcendent skill like Bird’s passing or Baylor’s hang time. If you want to dig deeper, his southern roots (as well as the damaging Cleo Hill incident) probably linger for many of the great black players from that era, none of whom seem that interested in singing his praises these days. (Russell battled Pettit in four separate NBA Finals and only mentioned

him once in

Second Wind

, with a little dig about how Pettit traveled every time he made an offensive move and the refs never called.) But you know what really killed Pettit historically? His hair. He made Locke on

Lost

look like Michael Landon. You can’t penalize him for that. You also can’t penalize him for Russell’s injury in the ’58 Finals; only one year earlier, Boston needed a triple-OT Game 7 in the Finals to defeat the Hawks. If he played today, Pettit would shave his head, grow a Fu Manchu, get a prominent tattoo, wax his body, and look like a fucking bad-ass. Back then, it was perfectly fine for the league’s best power forward to look like he should be teaching eleventh-grade shop. You can’t judge.

16. JULIUS ERVING

Resume: 16 years, 14 quality, 16 All-Stars (5 ABA) … ’74, ’75, ’76 ABA MVP ’74, ’76 Playoffs MVP … ’81 NBA MVP … ’80 runner-up … Top 5 NBA (’78, ’80–’83), Top 10 NBA (’77, ’84), Top 5 ABA (’73–’76), Top 10 ABA (’72) … two All-Star MVP’s … ABA leader: scoring (3x) … 3-year NBA peak: 25–7–4 … best player on 2 ABA champs (’74, ’76 Nets) and 3 runner-ups (’77, ’80, ’82 Sixers), 3rd-best player on NBA champ (’83 Sixers) … ’76 Playoffs: 35–13–5 (13 G) … ’80 Playoffs: 25–8–4 (18 G) … career ABA: 28.7 PPG (1st), 12.1 RPG (3rd) … career: points (5th), steals (13th) … 30K-10K Club

The case against Doc being ranked this high: Couldn’t shoot a 15-footer … surprisingly subpar defender … too passive offensively … too nice a guy, not enough of a killer … more style than substance … unwittingly overrated by the national media because he was so gracious and well-spoken … put up his peak numbers in a ramshackle league where nobody played defense, then never approached those numbers after the merger … lost five straight playoff series in his NBA prime in which he barely outplayed Bob Gross (1977), got outplayed by Bob Dandridge (’78), played Larry Kenon to a draw (’79), played Jamaal Wilkes to a draw (’80) and got severely outplayed by Larry Bird (’81) … struggled enough

with sore knees in the late seventies that

SI

ran a March ’79 feature called “Hey, What’s Up with the Doc?”

62

… never won an NBA ring until Moses saved him.

The case for Doc being ranked this high: One of the most groundbreaking, important and influential players ever … one of the most exciting players ever … ushered in the Wait a Second, This Dunking Thing Is Really Fun! Era, which eventually turned basketball into a billion-dollar business … single-handedly carried the failing ABA for three extra years … excelled at finishing fast breaks like nobody except for Barkley and maybe LeBron … filled a crucial void in the seventies as “the only beloved black basketball player during a time when fans were turning against basketball because it was considered to be ‘too black’”… probably the captain of the Articulate and Classy All-Time NBA team … along with Cousy, Russell, Wilt, Bird, Magic, Elgin, Mikan and Jordan, one of the nine most

important

NBA players ever … did I mention that he carried

The Fish That Saved Pittsburgh

?

(Quick tangent:

Fish

was the goofier bastard cousin of

Fast Break.

Doc played Moses Guthrie, the star of the Pittsburgh Pisces, who have their season turned around by a young waterboy and a wacky astrologist. Highlight no. 1: Doc’s acting made Keanu Reeves look like Philip Seymour Hoffman. Highlight no. 2: Doc awkwardly takes a date to a playground at night, then does dunks for her with bad seventies music playing. Somehow this brings them closer together. Highlight no. 3: The basketball scenes are so poorly edited that in one scene, one of Doc’s teammates (Driftwood) takes a jumper, then they cut to him standing under the basket as it goes in. Highlight no. 4: They play Kareem’s Lakers in the climactic scene and

everyone

has a glazed “Instead of paying us in cash, can’t they

pay us in coke?” look. Highlight no. 5: Kareem disappears for the entire fourth quarter for reasons that remain unclear. It’s never mentioned or addressed. Phenomenal. I love this movie.)

Back to the “nine most important players ever” point: What happens to professional basketball without Julius Winfield Erving? Elgin and Russell turned a horizontal game into a vertical one, but Doc grabbed the torch, explored the limits of gravity and individual expression, ignited the playgrounds, delighted fans, inspired the likes of Thompson and Jordan and stamped his creative imprint on everything we’re watching today. He’s like Cousy in this respect; Cousy showed that you could entertain NBA fans while you tried to win and so did Doc. They just did it in different ways. Cousy modernized professional basketball; Doc colorized it, repossessed it, turned it into a black man’s game. If he’d never showed up, would it have happened anyway? Yeah, probably. But it’s like Apple with home computers, Bill James with baseball statistics, Lorne Michaels with sketch comedy … maybe the seeds for the revolution were in place, but somebody had to have the foresight to water those seeds and see what would happen. For basketball, that person ended up being Doc.

His glory years happened in the ABA, with little record of what happened because those teams could barely get fans to show up (much less land a local TV contract). Doc’s eye-popping statistics overshadow the meat of the story: few professional athletes were ever described in such glowing, you-had-to-be-there-to-understand terms. It’s like hearing William Goldman try to describe watching Brando in his prime on Broadway and ultimately failing, but in the process of failing, he was so passionate about it that the point was still made. Everyone in the ABA revered Doc. There was an implicit understanding that he was the league’s meal ticket, the one player who could never be undercut, clotheslined, elbowed, or injured.

63

His open-court dunks had such a galvanizing effect on crowds—not just home crowds, but away crowds—that Hubie Brown created a “no dunks for Doc” rule for Kentucky home games because any

exciting Doc dunk turned the crowd against the Colonels. (Now that’s a magical player—when you can sway opposing crowds to your side, you know you’ve accomplished something.) His foul line slam in the ’76 Slam Dunk Contest remains one of the single most thrilling basketball moments that ever happened. It almost caused a fucking riot. And if you’re wondering about Doc’s ceiling as a basketball player, his five-game stretch in the ’76 Finals ranks among the greatest ever submitted at any level: 45–12, 48–14, 31–10, 34–15, 31–19 with none other than Bobby Jones defending him.