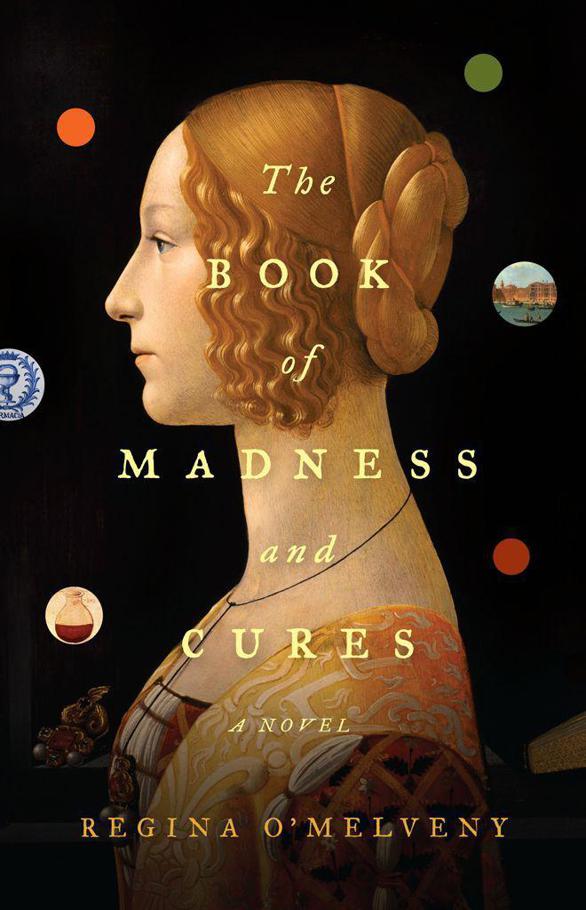

The Book of Madness and Cures

Read The Book of Madness and Cures Online

Authors: Regina O'Melveny

In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitute unlawful piracy and theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights.

For Bill and Adrienne

Nullaque iam tellus,

nullus mihi permanet aër,

Incola ceu nusquam,

sic sum peregrinus ubique.

No land now, no air

is constant for me.

Because I dwell nowhere,

I’m a pilgrim everywhere.

—

Petrarch

Le aque sta via ani e mesi, e po’ le torna ai so paesi.

The waters vanish for months and years and then return to their home.

—

Sixteenth-century Venetian proverb

That which wounds, shall heal.

—

Attributed to the oracle of Apollo

“I don’t know

where my own body begins or ends,” said the young girl of Imizmiza. Her mother had summoned me, the only woman physician within hundreds of miles, to tend her twelve-year-old daughter, who suffered the grave consequences of corporeal confusion. The girl sat at a cedar table near a narrow window in the red earthen house. She told me, through a dark veil that flickered as she spoke, that she sensed the fear of entrapment that the tethered horse knew in the field. His visible breath pulsed in the cold air as he drew the rope taut, while the groom approached, currycomb in hand. She told me, “The man who strokes the horse with five different brushes in strict order of succession, the man with a head like the knot at the end of a rope, he is smaller than my thumb—” And then she laughed suddenly, surprising me.

Before I could puzzle this out, her mother approached us and chided, “Come, Lalla, put on your riding skirts. You’re taking the horse out today.”

The girl stared at the plank table where her left arm lay with the grain, her right arm resting bent against it. She whispered, “I’m too heavy today, I can’t move.”

And though she made an effort, she couldn’t budge.

When I placed my hand upon the wood lightly, as if touching the fuzzy scalp of an infant, she sighed and closed her eyes. When I removed my hand, she sensed it immediately. I tried to lift her arms from the table but she was rigid. Later, inclined by some inner urging, she separated herself and wandered as if in a trance, when at last her mother could direct her to her beloved horse or to her bed for an afternoon nap.

Wherever Lalla stopped, she became part of the thing she touched. When she rode her walleyed and snorting animal, she sweated like a horse. Froth gathered at her lips and neck. When she slept, she might not wake for days, for the bed itself was her motionless body. Meals were the most difficult. She refused whatever food she touched, confessing a horror of eating her own flesh. Though her mother fed her like a babe with a small wooden spoon, she grew thinner and thinner.

At length I suggested a slow cure. I would need the assistance of her mother and aunt—though the aunt, a large, choleric woman, obstinately insisted that Lalla was not in need of curing, and certainly (she glared, scrutinizing my face and my dress) not by a foreigner. The girl simply possessed a clairvoyant body, the aunt said, challenging me. “We mustn’t take away the girl’s talent.”

“The girl doesn’t have command of her own life! One must stand apart in order to truly know another,” I said.

Lalla’s mother, a small, dark mountain of a woman, also veiled, asked, “Will she be able to marry and bear children?”

“I don’t know,” I confessed.

The cure, then, consisted of words. I advised her mother to name her hand, to name the distaff upon the table, and the table itself. When I came to visit, I’d ask Lalla, “Where is your arm, your hand, your hip?” Sometimes she could answer and point to that part of her body. Other days she regarded me with a kind of panic, as if she didn’t understand my question and feared terrifying penalties for this. I touched her hand, and then her mother or aunt would repeat the word for hand, to calm her. Gradually she responded with more and more movement until her ability to unfasten herself from her surroundings was accompanied by a kind of plaintive joy. For separation meant that she had changed and that the unknown surged forward to meet her.

I’ve since come to believe that the world is populated by multitudes of women sitting at windows, inseparable from their surroundings. I myself spent many hours at a window on the Zattere, waiting for my father’s return, waiting for my life to appear like one of those great ships that came to harbor, broad sails filled with the wind of providence. I didn’t know then that during those fugitive hours beneath the influence of the damp moon, I was already plotting my future in pursuit of the past. I’d grown transparent as the glass through which I peered, dangerously invisible even to myself. It was then I knew I must set my life in motion or I would disappear.

God’s Work or the Devil’s Machinations

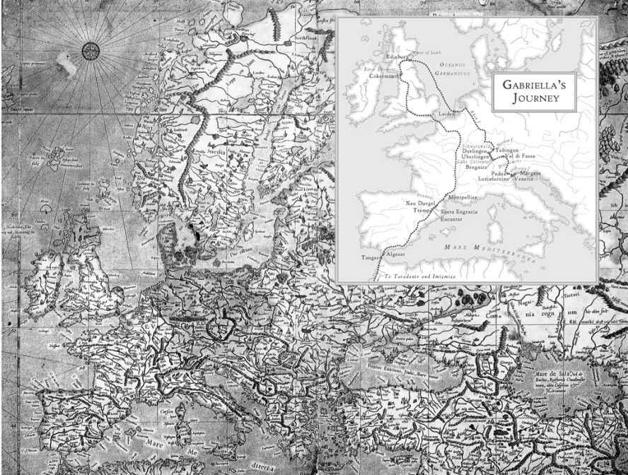

Venetia, 1590

From the foreign

marks and characters in diverse hands and languages upon the sheet of paper that enclosed it, I could see that my father’s present letter had traveled, a lost communiqué, through many of the cities on his route. It had been nearly a year since I’d heard from him. All told, he’d been gone since August of 1580. Olmina, once my nursemaid and now my servant, had slipped the letter lightly on my desk that stifling July afternoon. She may as well have released a viper that gives no warning before it strikes.

“If my mother reads this, you know she’ll twist it into some kind of offense, no matter what it contains,” I warned, tapping the closed letter nervously on my palm as we stood in my shuttered room, the summer tides slopping noisily on the stones below my window, the warm stench of brine stinging the air. Poor Mamma. She’d always perceived the world to be against her. Happiness was never to be trusted. And yet, I thought vaguely, neither was sorrow. Didn’t each come to season in the other? Sometimes our Venetia gleamed a miraculous city on the summer sea, and later during the winter

acqua alta,

she sank into cheerless facade. Then the floods engendered spring. Someday she might all be submerged, a dark siren whose lamplit eyes have gone out. Yet others might see beauty there where we walked in the place become water.

“Don’t worry, Signorina Gabriella.” Olmina pressed a forefinger beside her broad peasant’s nose, a sign that she knew how to keep a secret. Her pale blue eyes glinted in the dim light, though I’d seen those same lively eyes turn dull as slate when she was questioned by my needling mother.

“I don’t think she’s even missed him these ten years.”

“Ah, signorina. She seems to yearn for the role of widow…”

“So true, dear Olmina. But even there she’s unsuccessful. She’d have to give up her luxuries and frippery.” Though I often sensed a sad futility under her frivolous pursuits. There was more to her, perhaps, than I knew. I’d often seen a fear without cause flickering across her face. If she were a widow, she could wear it more openly, even though the source was still obscure.

“Well, if you don’t mind”—Olmina rolled her hands within her linen skirts, nodding, her gray hair poking out from under her pale, unraveling scarf—“I’ve a stack of dishes to wash in the scullery and my own luxury of a nap waiting for me at the end of that.” She grinned and then stumped down the stairs, her short, formidable figure still strong in middle age.