The Book Thief (47 page)

Authors: Markus Zusak

Tags: #Fiction, #death, #Storytelling, #General, #Europe, #Historical, #Juvenile Fiction, #Holocaust, #Children: Young Adult (Gr. 7-9), #Religious, #Books and reading, #Historical - Holocaust, #Social Issues, #Jewish, #Books & Libraries, #Military & Wars, #Books and reading/ Fiction, #Storytelling/ Fiction, #Historical Fiction (Young Adult), #Death & Dying, #Death/ Fiction, #Juvenile Fiction / Historical / Holocaust

“How was it down

there?” someone asked.

there?” someone asked.

Papa’s lungs

were full of sky.

were full of sky.

A few hours

later, when he’d washed and eaten and thrown up, he attempted to write a

detailed letter home. His hands were uncontrollable, forcing him to make it

short. If he could bring himself, the remainder would be told verbally, when

and if he made it home.

later, when he’d washed and eaten and thrown up, he attempted to write a

detailed letter home. His hands were uncontrollable, forcing him to make it

short. If he could bring himself, the remainder would be told verbally, when

and if he made it home.

To my dear Rosa

and Liesel,

he

began.

and Liesel,

he

began.

It took many

minutes to write those six words down.

minutes to write those six words down.

THE BREAD EATERS

It had been a

long and eventful year in Molching, and it was finally drawing to a close.

long and eventful year in Molching, and it was finally drawing to a close.

Liesel spent the

last few months of 1942 consumed by thoughts of what she called three desperate

men. She wondered where they were and what they were doing.

last few months of 1942 consumed by thoughts of what she called three desperate

men. She wondered where they were and what they were doing.

One afternoon,

she lifted the accordion from its case and polished it with a rag. Only once,

just before she put it away, did she take the step that Mama could not. She

placed her finger on one of the keys and softly pumped the bellows. Rosa had

been right. It only made the room feel emptier.

she lifted the accordion from its case and polished it with a rag. Only once,

just before she put it away, did she take the step that Mama could not. She

placed her finger on one of the keys and softly pumped the bellows. Rosa had

been right. It only made the room feel emptier.

Whenever she met

Rudy, she asked if there had been any word from his father. Sometimes he

described to her in detail one of Alex Steiner’s letters. By comparison, the

one letter her own papa had sent was somewhat of a disappointment.

Rudy, she asked if there had been any word from his father. Sometimes he

described to her in detail one of Alex Steiner’s letters. By comparison, the

one letter her own papa had sent was somewhat of a disappointment.

Max, of course,

was entirely up to her imagination.

was entirely up to her imagination.

It was with

great optimism that she envisioned him walking alone on a deserted road. Once

in a while she imagined him falling into a doorway of safety somewhere, his

identity card enough to fool the right person.

great optimism that she envisioned him walking alone on a deserted road. Once

in a while she imagined him falling into a doorway of safety somewhere, his

identity card enough to fool the right person.

The three men

would turn up everywhere.

would turn up everywhere.

She saw her papa

in the window at school. Max often sat with her by the fire. Alex Steiner

arrived when she was with Rudy, staring back at them after they’d slammed the

bikes down on Munich Street and looked into the shop.

in the window at school. Max often sat with her by the fire. Alex Steiner

arrived when she was with Rudy, staring back at them after they’d slammed the

bikes down on Munich Street and looked into the shop.

“Look at those

suits,” Rudy would say to her, his head and hands against the glass. “All going

to waste.”

suits,” Rudy would say to her, his head and hands against the glass. “All going

to waste.”

Strangely, one

of Liesel’s favorite distractions was Frau Holtzapfel. The reading sessions

included Wednesday now as well, and they’d finished the water-abridged version

of

The Whistler

and were on to

The Dream Carrier.

The old woman

sometimes made tea or gave Liesel some soup that was infinitely better than

Mama’s. Less watery.

of Liesel’s favorite distractions was Frau Holtzapfel. The reading sessions

included Wednesday now as well, and they’d finished the water-abridged version

of

The Whistler

and were on to

The Dream Carrier.

The old woman

sometimes made tea or gave Liesel some soup that was infinitely better than

Mama’s. Less watery.

Between October

and December, there had been one more parade of Jews, with one to follow. As on

the previous occasion, Liesel had rushed to Munich Street, this time to see if

Max Vandenburg was among them. She was torn between the obvious urge to see

him—to know that he was still alive—and an absence that could mean any number

of things, one of which being freedom.

and December, there had been one more parade of Jews, with one to follow. As on

the previous occasion, Liesel had rushed to Munich Street, this time to see if

Max Vandenburg was among them. She was torn between the obvious urge to see

him—to know that he was still alive—and an absence that could mean any number

of things, one of which being freedom.

In mid-December,

a small collection of Jews and other miscreants was brought down Munich Street

again, to Dachau. Parade number three.

a small collection of Jews and other miscreants was brought down Munich Street

again, to Dachau. Parade number three.

Rudy walked

purposefully down Himmel Street and returned from number thirty-five with a

small bag and two bikes.

purposefully down Himmel Street and returned from number thirty-five with a

small bag and two bikes.

“You game,

Saumensch

?”

Saumensch

?”

THE

CONTENTS OF RUDY’S BAG

CONTENTS OF RUDY’S BAG

Six stale pieces of bread,

broken into quarters.

They pedaled

ahead of the parade, toward Dachau, and stopped at an empty piece of road. Rudy

passed Liesel the bag. “Take a handful.”

ahead of the parade, toward Dachau, and stopped at an empty piece of road. Rudy

passed Liesel the bag. “Take a handful.”

“I’m not sure

this is a good idea.”

this is a good idea.”

He slapped some

bread onto her palm. “Your papa did.”

bread onto her palm. “Your papa did.”

How could she

argue? It was worth a whipping.

argue? It was worth a whipping.

“If we’re fast,

we won’t get caught.” He started distributing the bread. “So move it,

Saumensch.

”

we won’t get caught.” He started distributing the bread. “So move it,

Saumensch.

”

Liesel couldn’t

help herself. There was the trace of a grin on her face as she and Rudy

Steiner, her best friend, handed out the pieces of bread on the road. When they

were finished, they took their bikes and hid among the Christmas trees.

help herself. There was the trace of a grin on her face as she and Rudy

Steiner, her best friend, handed out the pieces of bread on the road. When they

were finished, they took their bikes and hid among the Christmas trees.

The road was

cold and straight. It wasn’t long till the soldiers came with the Jews.

cold and straight. It wasn’t long till the soldiers came with the Jews.

In the tree

shadows, Liesel watched the boy. How things had changed, from fruit stealer to

bread giver. His blond hair, although darkening, was like a candle. She heard

his stomach growl—and he was giving people bread.

shadows, Liesel watched the boy. How things had changed, from fruit stealer to

bread giver. His blond hair, although darkening, was like a candle. She heard

his stomach growl—and he was giving people bread.

Was this

Germany?

Germany?

Was this Nazi

Germany?

Germany?

The first

soldier did not see the bread—he was not hungry—but the first Jew saw it.

soldier did not see the bread—he was not hungry—but the first Jew saw it.

His ragged hand

reached down and picked a piece up and shoved it deliriously to his mouth.

reached down and picked a piece up and shoved it deliriously to his mouth.

Is that Max?

Liesel thought.

Liesel thought.

She could not

see properly and moved to get a better view.

see properly and moved to get a better view.

“Hey!” Rudy was

livid. “Don’t move. If they find us here and match us to the bread, we’re

history.”

livid. “Don’t move. If they find us here and match us to the bread, we’re

history.”

Liesel

continued.

continued.

More Jews were

bending down and taking bread from the road, and from the edge of the trees,

the book thief examined each and every one of them. Max Vandenburg was not

there.

bending down and taking bread from the road, and from the edge of the trees,

the book thief examined each and every one of them. Max Vandenburg was not

there.

Relief was

short-lived.

short-lived.

It stirred

itself around her just as one of the soldiers noticed a prisoner drop a hand to

the ground. Everyone was ordered to stop. The road was closely examined. The

prisoners chewed as fast and silently as they could. Collectively, they gulped.

itself around her just as one of the soldiers noticed a prisoner drop a hand to

the ground. Everyone was ordered to stop. The road was closely examined. The

prisoners chewed as fast and silently as they could. Collectively, they gulped.

The soldier

picked up a few pieces and studied each side of the road. The prisoners also

looked.

picked up a few pieces and studied each side of the road. The prisoners also

looked.

“In there!”

One of the

soldiers was striding over, to the girl by the closest trees. Next he saw the

boy. Both began to run.

soldiers was striding over, to the girl by the closest trees. Next he saw the

boy. Both began to run.

They chose

different directions, under the rafters of branches and the tall ceiling of the

trees.

different directions, under the rafters of branches and the tall ceiling of the

trees.

“Don’t stop

running, Liesel!”

running, Liesel!”

“What about the

bikes?”

bikes?”

“Scheiss drauf!

Shit on them, who cares!”

Shit on them, who cares!”

They ran, and

after a hundred meters, the hunched breath of the soldier drew closer. It

sidled up next to her and she waited for the accompanying hand.

after a hundred meters, the hunched breath of the soldier drew closer. It

sidled up next to her and she waited for the accompanying hand.

She was lucky.

All she received

was a boot up the ass and a fistful of words. “Keep running, little girl, you

don’t belong here!” She ran and she did not stop for at least another mile.

Branches sliced her arms, pinecones rolled at her feet, and the taste of

Christmas needles chimed inside her lungs.

was a boot up the ass and a fistful of words. “Keep running, little girl, you

don’t belong here!” She ran and she did not stop for at least another mile.

Branches sliced her arms, pinecones rolled at her feet, and the taste of

Christmas needles chimed inside her lungs.

A good

forty-five minutes had passed by the time she made it back, and Rudy was

sitting by the rusty bikes. He’d collected what was left of the bread and was

chewing on a stale, stiff portion.

forty-five minutes had passed by the time she made it back, and Rudy was

sitting by the rusty bikes. He’d collected what was left of the bread and was

chewing on a stale, stiff portion.

“I told you not

to get too close,” he said.

to get too close,” he said.

She showed him

her backside. “Have I got a footprint?”

her backside. “Have I got a footprint?”

THE HIDDEN SKETCHBOOK

A few days

before Christmas, there was another raid, although nothing dropped on the town

of Molching. According to the radio news, most of the bombs fell in open

country.

before Christmas, there was another raid, although nothing dropped on the town

of Molching. According to the radio news, most of the bombs fell in open

country.

What was most

important was the reaction in the Fiedlers’ shelter. Once the last few patrons

had arrived, everyone settled down solemnly and waited. They looked at her,

expectantly.

important was the reaction in the Fiedlers’ shelter. Once the last few patrons

had arrived, everyone settled down solemnly and waited. They looked at her,

expectantly.

Papa’s voice

arrived, loud in her ears.

arrived, loud in her ears.

“And if there

are more raids, keep reading in the shelter.”

are more raids, keep reading in the shelter.”

Liesel waited.

She needed to be sure that they wanted it.

She needed to be sure that they wanted it.

Rudy spoke for

everyone. “Read,

Saumensch.

”

everyone. “Read,

Saumensch.

”

She opened the

book, and again, the words found their way upon all those present in the

shelter.

book, and again, the words found their way upon all those present in the

shelter.

At home, once

the sirens had given permission for everyone to return aboveground, Liesel sat

in the kitchen with her mama. A preoccupation was at the forefront of Rosa

Hubermann’s expression, and it was not long until she picked up a knife and

left the room. “Come with me.”

the sirens had given permission for everyone to return aboveground, Liesel sat

in the kitchen with her mama. A preoccupation was at the forefront of Rosa

Hubermann’s expression, and it was not long until she picked up a knife and

left the room. “Come with me.”

She walked to

the living room and took the sheet from the edge of her mattress. In the side,

there was a sewn-up slit. If you didn’t know beforehand that it was there,

there was almost no chance of finding it. Rosa cut it carefully open and

inserted her hand, reaching in the length of her entire arm. When it came back

out, she was holding Max Vandenburg’s sketchbook.

the living room and took the sheet from the edge of her mattress. In the side,

there was a sewn-up slit. If you didn’t know beforehand that it was there,

there was almost no chance of finding it. Rosa cut it carefully open and

inserted her hand, reaching in the length of her entire arm. When it came back

out, she was holding Max Vandenburg’s sketchbook.

“He said to give

this to you when you were ready,” she said. “I was thinking your birthday. Then

I brought it back to Christmas.” Rosa Hubermann stood and there was a strange

look on her face. It was not made up of pride. Perhaps it was the thickness,

the heaviness of recollection. She said, “I think you’ve always been ready,

Liesel. From the moment you arrived here, clinging to that gate, you were meant

to have this.”

this to you when you were ready,” she said. “I was thinking your birthday. Then

I brought it back to Christmas.” Rosa Hubermann stood and there was a strange

look on her face. It was not made up of pride. Perhaps it was the thickness,

the heaviness of recollection. She said, “I think you’ve always been ready,

Liesel. From the moment you arrived here, clinging to that gate, you were meant

to have this.”

Rosa gave her

the book.

the book.

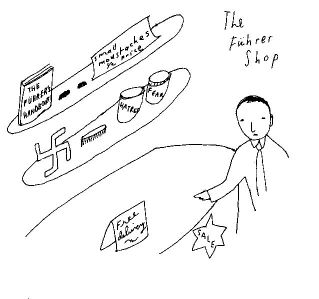

The cover looked

like this:

like this:

THE

WORD SHAKER

WORD SHAKER

A Small Collection

of Thoughts

for Liesel Meminger

Liesel held it

with soft hands. She stared. “Thanks, Mama.”

with soft hands. She stared. “Thanks, Mama.”

She embraced

her.

her.

There was also a

great longing to tell Rosa Hubermann that she loved her. It’s a shame she didn’t

say it.

great longing to tell Rosa Hubermann that she loved her. It’s a shame she didn’t

say it.

She wanted to

read the book in the basement, for old times’ sake, but Mama convinced her

otherwise. “There’s a reason Max got sick down there,” she said, “and I can

tell you one thing, girl, I’m not letting you get sick.”

read the book in the basement, for old times’ sake, but Mama convinced her

otherwise. “There’s a reason Max got sick down there,” she said, “and I can

tell you one thing, girl, I’m not letting you get sick.”

She read in the

kitchen.

kitchen.

Red and yellow

gaps in the stove.

gaps in the stove.

The Word Shaker.

She made her way

through the countless sketches and stories, and the pictures with captions.

Things like Rudy on a dais with three gold medals slung around his neck.

Hair

the color of lemons

was written beneath it. The snowman made an appearance,

as did a list of the thirteen presents, not to mention the records of countless

nights in the basement or by the fire.

through the countless sketches and stories, and the pictures with captions.

Things like Rudy on a dais with three gold medals slung around his neck.

Hair

the color of lemons

was written beneath it. The snowman made an appearance,

as did a list of the thirteen presents, not to mention the records of countless

nights in the basement or by the fire.

Of course, there

were many thoughts, sketches, and dreams relating to Stuttgart and Germany and

the

Führer.

Recollections of Max’s family were also there. In the end,

he could not resist including them. He had to.

were many thoughts, sketches, and dreams relating to Stuttgart and Germany and

the

Führer.

Recollections of Max’s family were also there. In the end,

he could not resist including them. He had to.

Then came page

117.

117.

That was where

The

Word Shaker

itself made its appearance.

The

Word Shaker

itself made its appearance.

It was a fable

or a fairy tale. Liesel was not sure which. Even days later, when she looked up

both terms in the

Duden Dictionary,

she couldn’t distinguish between the

two.

or a fairy tale. Liesel was not sure which. Even days later, when she looked up

both terms in the

Duden Dictionary,

she couldn’t distinguish between the

two.

On the previous

page, there was a small note.

page, there was a small note.

PAGE

116

116

Liesel—I almost scribbled this story out. I thought you

might be too old for such a tale, but maybe no one is. I

thought of you and your books and words, and this strange

story came into my head. I hope you can find some good in it.

She turned the

page.

page.

THERE WAS once a

strange, small man. He decided three important details about his life:

strange, small man. He decided three important details about his life:

1.

He would part his hair from the opposite side to everyone else.

He would part his hair from the opposite side to everyone else.

2.

He would make himself a small, strange mustache.

He would make himself a small, strange mustache.

3.

He would one day rule the world.

He would one day rule the world.

The young man

wandered around for quite some time, thinking, planning, and figuring out

exactly how to make the world his. Then one day, out of nowhere, it struck

him—the perfect plan. He’d seen a mother walking with her child. At one point,

she admonished the small boy, until finally, he began to cry. Within a few

minutes, she spoke very softly to him, after which he was soothed and even

smiled.

wandered around for quite some time, thinking, planning, and figuring out

exactly how to make the world his. Then one day, out of nowhere, it struck

him—the perfect plan. He’d seen a mother walking with her child. At one point,

she admonished the small boy, until finally, he began to cry. Within a few

minutes, she spoke very softly to him, after which he was soothed and even

smiled.

The young man

rushed to the woman and embraced her. “Words!” He grinned.

rushed to the woman and embraced her. “Words!” He grinned.

“What?”

But there was no

reply. He was already gone.

reply. He was already gone.

Yes, the Führer

decided that he would rule the world with words. “I will never fire a gun,” he

devised. “I will not have to.” Still, he was not rash. Let’s allow him at least

that much. He was not a stupid man at all. His first plan of attack was to

plant the words in as many areas of his homeland as possible.

decided that he would rule the world with words. “I will never fire a gun,” he

devised. “I will not have to.” Still, he was not rash. Let’s allow him at least

that much. He was not a stupid man at all. His first plan of attack was to

plant the words in as many areas of his homeland as possible.

He planted them

day and night, and cultivated them.

day and night, and cultivated them.

He watched them

grow, until eventually, great forests of words had risen throughout Germany....

It was a nation of farmed thoughts.

grow, until eventually, great forests of words had risen throughout Germany....

It was a nation of farmed thoughts.

WHILE THE words

were growing, our young Führer also planted seeds to create symbols, and these,

too, were well on their way to full bloom. Now the time had come. The Führer

was ready.

were growing, our young Führer also planted seeds to create symbols, and these,

too, were well on their way to full bloom. Now the time had come. The Führer

was ready.

He invited his

people toward his own glorious heart, beckoning them with his finest, ugliest

words, handpicked from his forests. And the people came.

people toward his own glorious heart, beckoning them with his finest, ugliest

words, handpicked from his forests. And the people came.

They were all

placed on a conveyor belt and run through a rampant machine that gave them a

lifetime in ten minutes. Words were fed into them. Time disappeared and they

now Knew everything they needed to Know. They were hypnotized.

placed on a conveyor belt and run through a rampant machine that gave them a

lifetime in ten minutes. Words were fed into them. Time disappeared and they

now Knew everything they needed to Know. They were hypnotized.

Other books

A Beautiful Place to Die by Malla Nunn

Submissive Beauty by Eliza Gayle

Give Yourself Away by Barbara Elsborg

Fire in the Mist by Holly Lisle

The Final Diagnosis by Arthur Hailey

Full Tilt by Rick Mofina

The Broken by ker Dukey

Ultimatum: The Proving Grounds by Wade Adrian

Walker's Wedding by Lori Copeland

Eternal Test of Time by Vistica, Sarah