The Book Thief (49 page)

Authors: Markus Zusak

Tags: #Fiction, #death, #Storytelling, #General, #Europe, #Historical, #Juvenile Fiction, #Holocaust, #Children: Young Adult (Gr. 7-9), #Religious, #Books and reading, #Historical - Holocaust, #Social Issues, #Jewish, #Books & Libraries, #Military & Wars, #Books and reading/ Fiction, #Storytelling/ Fiction, #Historical Fiction (Young Adult), #Death & Dying, #Death/ Fiction, #Juvenile Fiction / Historical / Holocaust

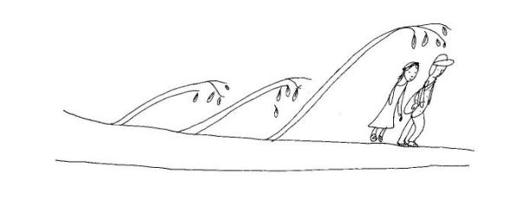

“It wouldn’t

stop growing,” she explained.

stop growing,” she explained.

“But neither

would this.” The young man looked at the branch that held his hand. He had a

point.

would this.” The young man looked at the branch that held his hand. He had a

point.

When they had

looked and talked enough, they made their way back down. They left the blankets

and remaining food behind.

looked and talked enough, they made their way back down. They left the blankets

and remaining food behind.

The people could

not believe what they were seeing, and the moment the word shaker and the young

man set foot in the world, the tree finally began to show the ax marks. Bruises

appeared. Slits were made in the trunk and the earth began to shiver.

not believe what they were seeing, and the moment the word shaker and the young

man set foot in the world, the tree finally began to show the ax marks. Bruises

appeared. Slits were made in the trunk and the earth began to shiver.

“It’s going to

fall!” a young woman screamed. “The tree is going to fall!” She was right. The

word shaker’s tree, in all its miles and miles of height, slowly began to tip.

It moaned as it was sucked to the ground. The world shook, and when everything

finally settled, the tree was laid out among the rest of the forest. It could

never destroy all of it, but if nothing else, a different-colored path was

carved through it.

fall!” a young woman screamed. “The tree is going to fall!” She was right. The

word shaker’s tree, in all its miles and miles of height, slowly began to tip.

It moaned as it was sucked to the ground. The world shook, and when everything

finally settled, the tree was laid out among the rest of the forest. It could

never destroy all of it, but if nothing else, a different-colored path was

carved through it.

The word shaker

and the young man climbed up to the horizontal trunk. They navigated the

branches and began to walk. When they looked back, they noticed that the

majority of onlookers had started to return to their own places. In there. Out

there. In the forest.

and the young man climbed up to the horizontal trunk. They navigated the

branches and began to walk. When they looked back, they noticed that the

majority of onlookers had started to return to their own places. In there. Out

there. In the forest.

But as they

walked on, they stopped several times, to listen. They thought they could hear

voices and words behind them, on the word shaker’s tree.

walked on, they stopped several times, to listen. They thought they could hear

voices and words behind them, on the word shaker’s tree.

For a long time,

Liesel sat at the kitchen table and wondered where Max Vandenburg was, in all

that forest out there. The light lay down around her. She fell asleep. Mama

made her go to bed, and she did so, with Max’s sketchbook against her chest.

Liesel sat at the kitchen table and wondered where Max Vandenburg was, in all

that forest out there. The light lay down around her. She fell asleep. Mama

made her go to bed, and she did so, with Max’s sketchbook against her chest.

It was hours

later, when she woke up, that the answer to her question came. “Of course,” she

whispered. “Of course I know where he is,” and she went back to sleep.

later, when she woke up, that the answer to her question came. “Of course,” she

whispered. “Of course I know where he is,” and she went back to sleep.

She dreamed of

the tree.

the tree.

THE

ANARCHIST’S SUIT COLLECTION

ANARCHIST’S SUIT COLLECTION

35

HIMMEL STREET,

HIMMEL STREET,

DECEMBER 24

With the absence of two fathers,

the Steiners have invited Rosa

and Trudy Hubermann, and Liesel.

When they arrive, Rudy is still in

the process of explaining his

clothes. He looks at Liesel and his

mouth widens, but only slightly.

The days leading

up to Christmas 1942 fell thick and heavy with snow. Liesel went through

The

Word Shaker

many times, from the story itself to the many sketches and

commentaries on either side of it. On Christmas Eve, she made a decision about

Rudy. To hell with being out too late.

up to Christmas 1942 fell thick and heavy with snow. Liesel went through

The

Word Shaker

many times, from the story itself to the many sketches and

commentaries on either side of it. On Christmas Eve, she made a decision about

Rudy. To hell with being out too late.

She walked next

door just before dark and told him she had a present for him, for Christmas.

door just before dark and told him she had a present for him, for Christmas.

Rudy looked at

her hands and either side of her feet. “Well, where the hell is it?”

her hands and either side of her feet. “Well, where the hell is it?”

“Forget it,

then.”

then.”

But Rudy knew.

He’d seen her like this before. Risky eyes and sticky fingers. The breath of

stealing was all around her and he could smell it. “This gift,” he estimated.

“You haven’t got it yet, have you?”

He’d seen her like this before. Risky eyes and sticky fingers. The breath of

stealing was all around her and he could smell it. “This gift,” he estimated.

“You haven’t got it yet, have you?”

“No.”

“And you’re not

buying it, either.”

buying it, either.”

“Of course not.

Do you think I have any money?” Snow was still falling. At the edge of the

grass, there was ice like broken glass. “Do you have the key?” she asked.

Do you think I have any money?” Snow was still falling. At the edge of the

grass, there was ice like broken glass. “Do you have the key?” she asked.

“The key to what?”

But it didn’t take Rudy long to understand. He made his way inside and returned

not long after. In the words of Viktor Chemmel, he said, “It’s time to go

shopping.”

But it didn’t take Rudy long to understand. He made his way inside and returned

not long after. In the words of Viktor Chemmel, he said, “It’s time to go

shopping.”

The light was

disappearing fast, and except for the church, all of Munich Street had closed

up for Christmas. Liesel walked hurriedly to remain in step with the lankier

stride of her neighbor. They arrived at the designated shop window.

STEINER—SCHNEIDERMEISTER.

The glass wore a thin sheet of mud and grime that had blown onto it in the

passing weeks. On the opposite side, the mannequins stood like witnesses. They

were serious and ludicrously stylish. It was hard to shake the feeling that

they were watching everything.

disappearing fast, and except for the church, all of Munich Street had closed

up for Christmas. Liesel walked hurriedly to remain in step with the lankier

stride of her neighbor. They arrived at the designated shop window.

STEINER—SCHNEIDERMEISTER.

The glass wore a thin sheet of mud and grime that had blown onto it in the

passing weeks. On the opposite side, the mannequins stood like witnesses. They

were serious and ludicrously stylish. It was hard to shake the feeling that

they were watching everything.

Rudy reached

into his pocket.

into his pocket.

It was Christmas

Eve.

Eve.

His father was

near Vienna.

near Vienna.

He didn’t think

he’d mind if they trespassed in his beloved shop. The circumstances demanded

it.

he’d mind if they trespassed in his beloved shop. The circumstances demanded

it.

The door opened

fluently and they made their way inside. Rudy’s first instinct was to hit the

light switch, but the electricity had already been cut off.

fluently and they made their way inside. Rudy’s first instinct was to hit the

light switch, but the electricity had already been cut off.

“Any candles?”

Rudy was

dismayed. “

I

brought the key. And besides, this was your idea.”

dismayed. “

I

brought the key. And besides, this was your idea.”

In the middle of

the exchange, Liesel tripped on a bump in the floor. A mannequin followed her

down. It groped her arm and dismantled in its clothes on top of her. “Get this

thing off me!” It was in four pieces. The torso and head, the legs, and two

separate arms. When she was rid of it, Liesel stood and wheezed. “Jesus, Mary.”

the exchange, Liesel tripped on a bump in the floor. A mannequin followed her

down. It groped her arm and dismantled in its clothes on top of her. “Get this

thing off me!” It was in four pieces. The torso and head, the legs, and two

separate arms. When she was rid of it, Liesel stood and wheezed. “Jesus, Mary.”

Rudy found one

of the arms and tapped her on the shoulder with its hand. When she turned in

fright, he extended it in friendship. “Nice to meet you.”

of the arms and tapped her on the shoulder with its hand. When she turned in

fright, he extended it in friendship. “Nice to meet you.”

For a few

minutes, they moved slowly through the tight pathways of the shop. Rudy started

toward the counter. When he fell over an empty box, he yelped and swore, then

found his way back to the entrance. “This is ridiculous,” he said. “Wait here a

minute.” Liesel sat, mannequin arm in hand, till he returned with a lit lantern

from the church.

minutes, they moved slowly through the tight pathways of the shop. Rudy started

toward the counter. When he fell over an empty box, he yelped and swore, then

found his way back to the entrance. “This is ridiculous,” he said. “Wait here a

minute.” Liesel sat, mannequin arm in hand, till he returned with a lit lantern

from the church.

A ring of light

circled his face.

circled his face.

“So where’s this

present you’ve been bragging about? It better not be one of these weird

mannequins.”

present you’ve been bragging about? It better not be one of these weird

mannequins.”

“Bring the light

over.”

over.”

When he made it

to the far left section of the shop, Liesel took the lantern with one hand and

swept through the hanging suits with the other. She pulled one out but quickly

replaced it with another. “No, still too big.” After two more attempts, she

held a navy blue suit in front of Rudy Steiner. “Does this look about your

size?”

to the far left section of the shop, Liesel took the lantern with one hand and

swept through the hanging suits with the other. She pulled one out but quickly

replaced it with another. “No, still too big.” After two more attempts, she

held a navy blue suit in front of Rudy Steiner. “Does this look about your

size?”

While Liesel sat

in the dark, Rudy tried on the suit behind one of the curtains. There was a

small circle of light and the shadow dressing itself.

in the dark, Rudy tried on the suit behind one of the curtains. There was a

small circle of light and the shadow dressing itself.

When he

returned, he held out the lantern for Liesel to see. Free of the curtain, the

light was like a pillar, shining onto the refined suit. It also lit up the

dirty shirt beneath and Rudy’s battered shoes.

returned, he held out the lantern for Liesel to see. Free of the curtain, the

light was like a pillar, shining onto the refined suit. It also lit up the

dirty shirt beneath and Rudy’s battered shoes.

“Well?” he

asked.

asked.

Liesel continued

the examination. She moved around him and shrugged. “Not bad.”

the examination. She moved around him and shrugged. “Not bad.”

“Not bad! I look

better than just not bad.”

better than just not bad.”

“The shoes let

you down. And your face.”

you down. And your face.”

Rudy placed the

lantern on the counter and came toward her in mock-anger, and Liesel had to

admit that a nervousness started gripping her. It was with both relief and

disappointment that she watched him trip and fall on the disgraced mannequin.

lantern on the counter and came toward her in mock-anger, and Liesel had to

admit that a nervousness started gripping her. It was with both relief and

disappointment that she watched him trip and fall on the disgraced mannequin.

On the floor,

Rudy laughed.

Rudy laughed.

Then he closed

his eyes, clenching them hard.

his eyes, clenching them hard.

Liesel rushed

over.

over.

She crouched

above him.

above him.

Kiss him,

Liesel, kiss him.

Liesel, kiss him.

“Are you all

right, Rudy? Rudy?”

right, Rudy? Rudy?”

“I miss him,”

said the boy, sideways, across the floor.

said the boy, sideways, across the floor.

“Frohe

Weihnachten,”

Liesel

replied. She helped him up, straightening the suit. “Merry Christmas.”

Weihnachten,”

Liesel

replied. She helped him up, straightening the suit. “Merry Christmas.”

PART NINE

the

last human stranger

last human stranger

featuring:

the next temptation—a cardplayer—

the snows of stalingrad—an ageless

brother—an accident—the bitter taste

of questions—a toolbox, a bleeder,

a bear—a broken plane—

and a homecoming

THE NEXT TEMPTATION

This time, there

were cookies.

were cookies.

But they were

stale.

stale.

They were

Kipferl

left over from Christmas, and they’d been sitting on the desk for at least

two weeks. Like miniature horseshoes with a layer of icing sugar, the ones on

the bottom were bolted to the plate. The rest were piled on top, forming a

chewy mound. She could already smell them when her fingers tightened on the

window ledge. The room tasted like sugar and dough, and thousands of pages.

Kipferl

left over from Christmas, and they’d been sitting on the desk for at least

two weeks. Like miniature horseshoes with a layer of icing sugar, the ones on

the bottom were bolted to the plate. The rest were piled on top, forming a

chewy mound. She could already smell them when her fingers tightened on the

window ledge. The room tasted like sugar and dough, and thousands of pages.

There was no

note, but it didn’t take Liesel long to realize that Ilsa Hermann had been at

it again, and she certainly wasn’t taking the chance that the cookies might

not

be for her. She made her way back to the window and passed a whisper

through the gap. The whisper’s name was Rudy.

note, but it didn’t take Liesel long to realize that Ilsa Hermann had been at

it again, and she certainly wasn’t taking the chance that the cookies might

not

be for her. She made her way back to the window and passed a whisper

through the gap. The whisper’s name was Rudy.

They’d gone on

foot that day because the road was too slippery for bikes. The boy was beneath

the window, standing watch. When she called out, his face appeared, and she

presented him with the plate. He didn’t need much convincing to take it.

foot that day because the road was too slippery for bikes. The boy was beneath

the window, standing watch. When she called out, his face appeared, and she

presented him with the plate. He didn’t need much convincing to take it.

His eyes feasted

on the cookies and he asked a few questions.

on the cookies and he asked a few questions.

“Anything else?

Any milk?”

Any milk?”

“What?”

“Milk,”

he repeated, a

little louder this time. If he’d recognized the offended tone in Liesel’s

voice, he certainly wasn’t showing it.

he repeated, a

little louder this time. If he’d recognized the offended tone in Liesel’s

voice, he certainly wasn’t showing it.

The book thief’s

face appeared above him again. “Are you stupid? Can I just steal the book?”

face appeared above him again. “Are you stupid? Can I just steal the book?”

“Of course. All

I’m saying is . . .”

I’m saying is . . .”

Liesel moved

toward the far shelf, behind the desk. She found some paper and a pen in the

top drawer and wrote

Thank you,

leaving the note on top.

toward the far shelf, behind the desk. She found some paper and a pen in the

top drawer and wrote

Thank you,

leaving the note on top.

To her right, a

book protruded like a bone. Its paleness was almost scarred by the dark

lettering of the title.

Die Letzte Menschliche

Fremde—The Last Human

Stranger.

It whispered softly as she removed it from the shelf. Some dust

showered down.

book protruded like a bone. Its paleness was almost scarred by the dark

lettering of the title.

Die Letzte Menschliche

Fremde—The Last Human

Stranger.

It whispered softly as she removed it from the shelf. Some dust

showered down.

At the window,

just as she was about to make her way out, the library door creaked apart.

just as she was about to make her way out, the library door creaked apart.

Her knee was up

and her book-stealing hand was poised against the window frame. When she faced

the noise, she found the mayor’s wife in a brand-new bathrobe and slippers. On

the breast pocket of the robe sat an embroidered swastika. Propaganda even

reached the bathroom.

and her book-stealing hand was poised against the window frame. When she faced

the noise, she found the mayor’s wife in a brand-new bathrobe and slippers. On

the breast pocket of the robe sat an embroidered swastika. Propaganda even

reached the bathroom.

They watched

each other.

each other.

Liesel looked at

Ilsa Hermann’s breast and raised her arm. “

Heil

Hitler.”

Ilsa Hermann’s breast and raised her arm. “

Heil

Hitler.”

She was just

about to leave when a realization struck her.

about to leave when a realization struck her.

The cookies.

They’d been

there for weeks.

there for weeks.

That meant that

if the mayor himself used the library, he must have seen them. He must have

asked why they were there. Or—and as soon as Liesel felt this thought, it

filled her with a strange optimism—perhaps it wasn’t the mayor’s library at

all; it was hers. Ilsa Hermann’s.

if the mayor himself used the library, he must have seen them. He must have

asked why they were there. Or—and as soon as Liesel felt this thought, it

filled her with a strange optimism—perhaps it wasn’t the mayor’s library at

all; it was hers. Ilsa Hermann’s.

She didn’t know

why it was so important, but she enjoyed the fact that the roomful of books

belonged to the woman. It was she who introduced her to the library in the

first place and gave her the initial, even literal, window of opportunity. This

way was better. It all seemed to fit.

why it was so important, but she enjoyed the fact that the roomful of books

belonged to the woman. It was she who introduced her to the library in the

first place and gave her the initial, even literal, window of opportunity. This

way was better. It all seemed to fit.

Just as she

began to move again, she propped everything and asked, “This is your room,

isn’t it?”

began to move again, she propped everything and asked, “This is your room,

isn’t it?”

The mayor’s wife

tightened. “I used to read in here, with my son. But then . . .”

tightened. “I used to read in here, with my son. But then . . .”

Liesel’s hand

touched the air behind her. She saw a mother reading on the floor with a young

boy pointing at the pictures and the words. Then she saw a war at the window.

“I know.”

touched the air behind her. She saw a mother reading on the floor with a young

boy pointing at the pictures and the words. Then she saw a war at the window.

“I know.”

An exclamation

entered from outside.

entered from outside.

“What did you

say?!”

say?!”

Liesel spoke in

a harsh whisper, behind her. “Keep quiet,

Saukerl,

and watch the

street.” To Ilsa Hermann, she handed the words slowly across. “So all these

books . . .”

a harsh whisper, behind her. “Keep quiet,

Saukerl,

and watch the

street.” To Ilsa Hermann, she handed the words slowly across. “So all these

books . . .”

“They’re mostly

mine. Some are my husband’s, some were my son’s, as you know.”

mine. Some are my husband’s, some were my son’s, as you know.”

There was

embarrassment now on Liesel’s behalf. Her cheeks were set alight. “I always

thought this was the mayor’s room.”

embarrassment now on Liesel’s behalf. Her cheeks were set alight. “I always

thought this was the mayor’s room.”

“Why?” The woman

seemed amused.

seemed amused.

Liesel noticed

that there were also swastikas on the toes of her slippers. “He’s the mayor. I

thought he’d read a lot.”

that there were also swastikas on the toes of her slippers. “He’s the mayor. I

thought he’d read a lot.”

The mayor’s wife

placed her hands in her side pockets. “Lately, it’s you who gets the most use

out of this room.”

placed her hands in her side pockets. “Lately, it’s you who gets the most use

out of this room.”

“Have you read

this one?” Liesel held up

The Last Human Stranger.

this one?” Liesel held up

The Last Human Stranger.

Ilsa looked more

closely at the title. “I have, yes.”

closely at the title. “I have, yes.”

“Any good?”

“Not bad.”

There was an

itch to leave then, but also a peculiar obligation to stay. She moved to speak,

but the available words were too many and too fast. There were several attempts

to snatch at them, but it was the mayor’s wife who took the initiative.

itch to leave then, but also a peculiar obligation to stay. She moved to speak,

but the available words were too many and too fast. There were several attempts

to snatch at them, but it was the mayor’s wife who took the initiative.

Other books

Herculeah Jones Tarot Says Beware by Betsy Byars

Orbital Decay by A. G. Claymore

Insider by Micalea Smeltzer

Electroboy by Andy Behrman

Whispers on the Wind (A Prairie Hearts Novel Book 5) by Caroline Fyffe

The Split by Tyler, Penny

The Body in the Wardrobe by Katherine Hall Page

Tough to Tame by Diana Palmer

You'll Grow Out of It by Jessi Klein

Families and Other Nonreturnable Gifts by Claire Lazebnik