The Books of Elsewhere, Vol. 1: The Shadows (16 page)

Read The Books of Elsewhere, Vol. 1: The Shadows Online

Authors: Jacqueline West

BOOK: The Books of Elsewhere, Vol. 1: The Shadows

4.33Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Olive peeked through the keyhole. Mrs. Nivens stood on the porch. She wore a spotless apron, a perfectly ironed dress, and a smile that, when Olive opened the door, looked like it might slide off of her face and shatter on the stoop.

“Good evening, Mrs. Nivens,” said Olive politely.

“Hello, Olive, dear.” Mrs. Nivens looked down at the pool of water that was forming around Olive’s feet. “Were you—swimming?”

“I was just taking a shower,” said Olive.

“In your clothes?” asked Mrs. Nivens, whose voice had gone up a key.

“They were dirty too,” said Olive.

“I see.” Mrs. Nivens nodded slowly. A few droplets of water from the pool at Olive’s feet trailed over the doorjamb and plopped onto the porch.

“Well, I brought you a plate of chocolate raisin cookies,” Mrs. Nivens went on bravely, holding out a foil-wrapped plate. Olive took the plate in her wet hands. “But don’t spoil your dinner, now.”

“Thank you very much, Mrs. Nivens,” said Olive.

“You’re welcome,” said Mrs. Nivens. She gave Olive a long, hard look. “Are you sure you’re all right, Olive?”

Olive nodded hard, hoping Mrs. Nivens would leave before a talking cat or escapee from a painting showed up.

“It’s a funny old house, isn’t it?” Mrs. Nivens murmured. Her eyes left Olive’s face and slowly scanned the hallway, trailing up the stairs. “So much history. I haven’t been inside in ages, but I can still remember almost every detail—”

“Uh-huh,” said Olive quickly. “Well, I’ll call you if I need anything. Thank you again for the cookies.” She slammed the door shut before Mrs. Nivens could say another word.

Olive peeked through the front window and watched Mrs. Nivens go side-wise down the porch stairs, keeping one eye on the house, before scuttling down the walk toward her own house. Then Olive locked the door. She didn’t want Mrs. Nivens’s help. There was something about the way Mrs. Nivens looked at her that made Olive want to tell lies. Olive leaned against the door, keeping her eyes peeled, and absently munched a cookie. If Annabelle was waiting for Olive to drown so that she could get the necklace back, she probably wouldn’t have gone far.

Olive wondered how one went about getting rid of a person who had come out of a painting. Annabelle wasn’t alive, after all. What did people use to destroy paint? Soap and water? Turpentine? A paint scraper?

Olive was brushing a streak of crumbs off of her wet clothes when a furry orange cannonball shot down the stairs in two bounds and crashed into Olive’s shins.

“Now is the time!” puffed Horatio, staggering onto his feet. “We need your help—Ms. McMartin is loose!”

17

O

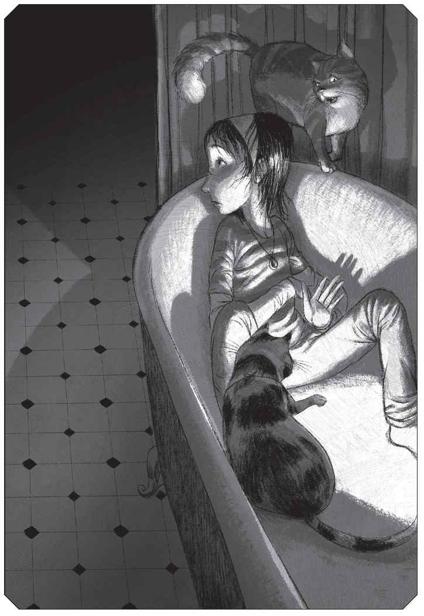

LIVE, HORATIO, AND Harvey, freshly escaped from the attic, held a hushed conference in one of the upstairs bathtubs. There were no paintings in this bathroom, and Horatio had selected the spot as the safest base of operations.

LIVE, HORATIO, AND Harvey, freshly escaped from the attic, held a hushed conference in one of the upstairs bathtubs. There were no paintings in this bathroom, and Horatio had selected the spot as the safest base of operations.

Still wet and wobbly, Olive huddled against the tub wall and gave both cats a long, cautious look. Could they really be what Morton’s neighbors had said? She glanced from one to the other. Harvey’s eye patch had disappeared. Instead, he was wearing a small metal breastplate, which looked as if it had been made from tuna cans and pop tabs.

“Who does he think he is tonight?” Olive whispered to Horatio.

“Lancelot du Lac,” Horatio whispered back.

Harvey gave Olive a gallant bow.

“First things first,” said Horatio. “Have you still got the necklace?”

Olive reached into the neck of her damp shirt and slowly, shakily, pulled out the pendant. Horatio gave a sigh of relief.

Harvey’s eyes went wild.

“Blackpaw’s booty!” he exclaimed. “The buried treasure of the pirate king!”

Horatio’s eyes became two thin green slits. “It was you?” he hissed. “You knew where it was all along?” His head swiveled toward Harvey like the gun on an army tank. “You took it from Ms. McMartin’s body and decided to

play pirate with it?!

”

play pirate with it?!

”

Thick orange fur bristling, Horatio pulled himself into pre-launch position.

“You dare to challenge zee greatest knight of all?” growled Harvey in a French accent, turning into a smaller but equally bristly hump.

“Wait! Wait!” said Olive, throwing herself between the cats and pinning them to the tub walls. Harvey let out an angry hiss above her elbow. “We can’t waste time like this!” she insisted. “I need to know what’s going on here. Then we can make a plan. Agreed?”

“Fine,” Horatio muttered.

“I grant my opponent’s plea for mercy,” said Harvey magnanimously.

“Good.” Olive took a deep breath and looked closely at both cats. “But first, I need to know one thing.” Olive tried to keep her voice from wavering. “Do you actually work for Aldous McMartin? Are you . . .

witches’ familiars?

”

witches’ familiars?

”

Harvey and Horatio glanced across the tub at each other. Harvey looked down at Olive’s toes. Finally, Horatio sighed. “We have belonged to the McMartin family for hundreds of years,” he said. “Longer than any of us can remember. And, yes, they are a line of powerful witches, and, yes, it was our role to serve them.”

“Even if we didn’t want to,” Harvey put in, still looking at Olive’s toes.

“So why wouldn’t Leopold just tell me how old he was?” asked Olive.

“Can you remember what you had for dinner last Monday?” Horatio challenged. “Try remembering your age if you predate paper.”

Olive tried to imagine this. She couldn’t. In fact, she couldn’t even remember when paper was invented.

“Aldous McMartin was the worst of the lot,” Horatio went on. “Greedy, cruel, dangerous. And brilliant. He was so hated and feared in Scotland that one night a band of townspeople set fire to the McMartin homestead, where the family had lived for centuries. They destroyed the family plot, smashed the headstones, dug up the graves, and burned what they found. After escaping to America, Aldous had everything that remained of the family graveyard brought here—”

“Everything?”

squeaked Olive, hugging her knees.

squeaked Olive, hugging her knees.

Horatio gave her a sharp look. “—and built a new home for the McMartin line on top of it, to preserve the power of the family.” Here Horatio paused, studying his front paw. “But things didn’t work out quite as Aldous had hoped.”

“What do you mean?” asked Olive.

“His son, Albert, was a huge disappointment.”

“’E was nice,” Harvey piped up. “Nice and stupeed.”

“Albert had no talent for witchcraft. In fact, he had no talents at all. The only good thing Albert ever did, as far as Aldous was concerned, was have a daughter. Annabelle.”

“Annabelle!” Olive gasped.

“Yes, Annabelle McMartin. And Annabelle was everything her grandfather could have hoped for: intelligent, greedy, and cruel.”

Olive thought she might be sick. “Then, I guess . . . I did something terrible.” Olive looked from Horatio to Harvey and back to Horatio. “I let her out. She said her name was Annabelle, and she was sad, and . . .” Olive trailed off, feeling exceptionally silly. “But I didn’t know it was her! Annabelle is young and pretty, and Ms. McMartin was an old woman . . .”

“Well, she wasn’t always old, you twit!” Horatio snapped.

“How dare you speak to a lady zat way!” demanded Harvey, looking ready to start a duel over whatever conflict was handy.

Olive stifled a frustrated scream. “Why didn’t you warn me?”

“We

tried

!” Horatio exploded. “We gave you hint after hint! We told you to be careful if you went into the paintings. We told you not to bring things out. But we were forbidden to directly interfere with the McMartins’ plans.” Horatio’s voice dropped, and a note of sadness trickled into it. “You know what we are, Olive. We belonged to them. We belong to their house.”

tried

!” Horatio exploded. “We gave you hint after hint! We told you to be careful if you went into the paintings. We told you not to bring things out. But we were forbidden to directly interfere with the McMartins’ plans.” Horatio’s voice dropped, and a note of sadness trickled into it. “You know what we are, Olive. We belonged to them. We belong to their house.”

“But zen you came along . . .” Harvey put in.

“Yes.” Horatio sighed. “None of us thought you would discover so much so quickly, or that Annabelle’s plans would come to pass. But you did, and they have. And if we don’t want the McMartins controlling us again, we can’t be cautious anymore.”

“Oui,” said Harvey. “Ze time has come for us to take a stand.”

“But what does Annabelle want?!” Olive threw up her hands. “Why was she in a painting? Why do the paintings come to life? How did the people in the paintings get inside in the first place?”

“Keep your voice down,” snapped Horatio. “Now that things can’t get much worse, I might as well tell you the whole story. Listen closely, and stop interrupting, if you possibly can.” Horatio took a provoking pause, as if daring Olive to speak. Then, at last, he began:

“More than anything else, Aldous McMartin wanted to control life. He wanted to create it, trap it, make it last forever. First, he made the paintings—little worlds that could come to life if seen through a pair of enchanted spectacles. Because he had created the paintings, he had power over them. He could watch what went on inside, and use the paintings as windows, in a way, to keep an eye on the entire house. As he practiced, he got better and better at it. He painted portraits that could come to life, and that would even have the personalities of the people he had painted, but with one big improvement: These people could live forever. Sometimes he painted people as a reward, as he did for Annabelle. In her portrait, she would always be young and lovely, and she would always be loyal to him.

“Next, he learned to trap living people in paintings,” said Horatio, pacing up and down the lip of the tub. “To make them

become

paintings. They weren’t dead, exactly, but they weren’t alive anymore either. They were . . . Elsewhere. That’s what he did to the neighbors on Linden Street who knew too much about Old Man McMartin, as they called him. It’s what he did to the builders who could have given away the secret of the gravestones, or to anyone else he disliked. Sometimes he just did it for fun. Like a collector pinning a living butterfly to a piece of cardboard.”

become

paintings. They weren’t dead, exactly, but they weren’t alive anymore either. They were . . . Elsewhere. That’s what he did to the neighbors on Linden Street who knew too much about Old Man McMartin, as they called him. It’s what he did to the builders who could have given away the secret of the gravestones, or to anyone else he disliked. Sometimes he just did it for fun. Like a collector pinning a living butterfly to a piece of cardboard.”

In Olive’s mind, the fragments of the story whirled and shifted. But this time, when they settled, she could see the whole picture. It had been there, in pieces, all along. “That was what he did to Morton,” she breathed.

Horatio gave the tiniest nod.

“Morton was telling the truth. And I didn’t believe him.” The words felt as heavy as pebbles in her mouth. “He was alive. And you helped bring him here, and Aldous McMartin trapped him, and now . . . what?” Olive choked. “He’s trapped forever? How could you do that to him?”

“Zat was the part I didn’t like,” said Harvey softly.

“Then why did you help Aldous McMartin?” demanded Olive furiously. “Why did you spy for him? Why did you trick innocent people?”

“We didn’t have much choice!” retorted Horatio. “If you had ever been an indentured servant for a family of witches, you might begin to understand. Besides,” the cat huffed, “we didn’t always obey. After Aldous trapped the little boy from next door, I refused to help him anymore. Once, we even destroyed his paints and canvases.”

“Oui. Zat was fun,” said Harvey, gazing toward the ceiling and swiping his paw through an imaginary bit of cloth.

“But then he got that

dog

. . .” said Horatio.

dog

. . .” said Horatio.

“Baltus,” hissed Harvey.

“. . . and that helped Aldous keep us out of the way for a while. It took us years to get Baltus hidden away in that painting. And then you, Little Miss Rescue Crew, came along and let him out.”

“Baltus!” Olive shouted so suddenly that both cats jumped. “I could hear Baltus even without the spectacles. And I could see Morton moving in the forest. The builders—their eyes glittered. And I noticed the necklace glinting in the lake before I put the spectacles on!” She looked from one cat to the other. “So the things that were from the real world . . . they still seem real in the paintings, even without the spectacles!”

“Very good,” said Horatio, raising his whiskered eyebrows slightly. “Aldous never did get the things he’d taken from the real world to blend in completely.”

“Wait a minute.” Olive crossed her arms, frowning.

Other books

ThinandBeautiful.com by Liane Shaw

Truth Will Out by Pamela Oldfield

Bloodstream by Luca Veste

And She Was by Cindy Dyson

Mayan December by Brenda Cooper

Sins of the Mother by Victoria Christopher Murray

Any Day Now by Denise Roig

Raggy Maggie by Barry Hutchison

Touch Me: Erotica Book 1 (The Virgin to Vixen Series) by Waters, Crystal C.

Spree by Collins, Max Allan