The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind (22 page)

Read The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind Online

Authors: William Kamkwamba

As usual, that night a strong wind was blowing.

A

S

I

EXPLAINED TO

Rose, the windmill wouldn’t work without wind. On calm, quiet nights, I’d still be stuck in the dark looking for matches. The only way I could change this was to find a battery. But while I waited for one, I still managed to use my windmill for other purposes.

My cousin Ruth, who was Uncle Socrates’ daughter, happened to be visiting from Mzuzu town. She was older and married and had a mobile phone, and often, she would bug me to take it to the trading center and charge it for her. A few guys in the trading center were making loads of money charging phones for people who didn’t have electricity in their homes. These guys would cut deals with shopkeepers, who allowed them to string an extension cord out the door, where they kept a small shaded stall. They sold scratch cards for phone units, and a few even had mobile phones on a table and you could pay to make calls, kind of like an open-air phone booth. These stalls can be found all over Malawi. In the bigger towns like Lilongwe, some guys even powered photocopiers and electric typewriters this way, and let people prepare their résumés and then call about an available job—all on the sidewalk or the dirt road. Of course, the constant blackouts weren’t so good for their businesses.

One day I was complaining about taking Ruth’s phone to the trading

center again when she said, “Why can’t you just charge phones with your windmill? It produces electricity, doesn’t it?”

I’d already thought about this, but I knew I didn’t get enough voltage from my bicycle dynamo to power a charger. My dynamo produced twelve volts, but a charger needs two hundred twenty. Twelve volts was fine for a lightbulb, but not strong enough for heavier jobs.

I had already discovered that energy decreases as it passes through wire over long distances. I used that concept when testing the radio against the dynamo. But for this, I needed to build something called a step-up transformer.

Power companies across the world, especially in Europe and America, step up power all the time. Huge alternators generate electricity in a power station, but as my previous experiment demonstrated, it loses strength on the way to your home. To remedy this, the power company installs step-up transformers in places along the route that boost the power before sending it on its way.

A step-up transformer has two coils—the primary and secondary—that are wrapped side by side around a core. Alternating current flows back and forth and is constantly changing, and this change causes the primary coil to induce a charge in the secondary coil. This process is called mutual induction, which means that voltage from one coil jumps into another. The result is that the overall voltage is increased. I had learned about this in a chapter in

Explaining Physics

entitled “Mutual Induction and Transformers,” which also featured a picture of a man with white hair and a bow tie. This was Michael Faraday, who invented the first transformer in 1831. What a good feeling that must have been.

Using the diagrams from this chapter, I was determined to make my own step-up transformer. First, I used some sharp pliers and cut an iron sheet into an “E.” The diagram demonstrated twenty-four volts being transformed to two hundred forty. I knew that voltage increased with each turn of the wire. The diagram showed the primary coil to have two hundred turns, while the secondary had two thousand. A bunch of mathematical equations were below the diagram—I assumed they explained how I

could make my own conversions—but instead, I just started wrapping like mad and hoped it would work.

I connected the dynamo wires to the primary coil, while the secondary coil was wired directly to the prongs of a phone charger. I got quite a shock while I was tying those bare wires to the charger, but once they were attached, I was ready to plug in the phone. Ruth was standing over me, watching carefully.

“Don’t blow it up,” she said.

“I know what I’m doing,” I said, lying.

I plugged in the phone jack, but instead of blowing up, the screen lit up and the bars began moving up and down the side. It worked!

“See,” I said. “Told you.”

To make things easier, I went a step further and made an electrical socket in my wall, just like at Gilbert’s house. I had a radio that operated on both batteries and AC electricity. In these kinds of radios, one end of the power cord usually plugs into the AC socket, and the other end goes into the wall of your house.

To get electricity in my room, I simply transferred this system into my wall. I pulled out the entire AC socket from the radio and fixed it into a wall mount made from flattened PVC pipe. I cut a hole in my wall and installed the mount so it looked a like a normal electrical socket, then connected the windmill wires from the outside. I reattached the radio’s power cord to the AC socket, then cut off the electrical plug that normally shoves into the wall. Taking those severed wires, I attached them directly to the phone charger. It was kind of backwards, but it worked. When news of the invention reached the trading center, the line of people arriving to charge their phones reached the road.

Most of the time people still pretended to be skeptical that I could do this. I think they were hoping I wouldn’t charge them money.

“Are you sure this thing can charge my phone?”

“I’m positive.”

“Prove it.”

“See, it charges.”

“My God, you’re right. But leave it for a little while longer. I’m still not convinced.”

After two months of using this method, I finally went bigger. I was always on the lookout for a car battery, then one day I noticed that Charity had one at his house.

“I found it on the road,” he said. “It must’ve fallen off a truck.”

Wherever it came from, I started begging and pleading with him, until finally he agreed to sell it to me on installments.

From studying my books, I knew that in order to charge the battery—which uses DC power—I had to first convert the AC power produced by the bicycle dynamo. My book talked about certain things called diodes, or rectifiers, which are found in many radios and electronic devices and convert the power for you. The type of rectifier I needed looked like a tiny D-cell battery on a long metal skewer and reminded me of the smoked mice that young boys sell on the roadside as snacks. Studying the picture, I opened one of my broken six-volt radios and easily found a diode. Once again, I fashioned a soldering iron out of a thick metal cable I heated in the fire, then fused the diode to the wire between the windmill and battery. It was so simple. I then replaced the standard AC phone charger with a DC model that plugs into a car’s cigarette lighter—a gift from my cousin Ruth.

With the battery, I was also now able to install three additional bulbs in the house, all running on a parallel circuit. For some reason, the light from the bicycle dynamo still worked using DC power. However, regular incandescent bulbs used in most homes will only work with AC power, so I had to look for alternatives. I managed to find small car bulbs in Daud’s shop that worked on DC—one was a brake light, and the others were headlamps. I installed one bulb outside, just above my door, another in my parents’ bedroom, and one in the living room. When the battery was fully charged, it could store enough power for three full days, even when the wind was still.

I constructed a simple light switch for each bulb using bicycle spokes and strips of iron. For the toggles, I wanted a good nonconductive material that I could easily shape the way I wanted. So taking my knife, I carved

out several round buttons from my old broken pair of flip-flops. I mounted these switches inside small boxes I’d made from melted PVC pipe.

A standard light switch has three separate wires: one from the power supply to the switch, one from the switch to the bulb, and one from the bulb to the power supply. Whenever I pushed the flip-flop button, the spoke and iron connected the terminals, completing the circuit.

Finally, I could touch the wall and get lights!

Not long after I’d completed this wiring, I walked into the living room one night and found my family sitting around, listening to the radio. My mother sat on the floor in the corner, crocheting a beautiful orange tablecloth. My father and sisters just stared ahead, lost in the news program on Radio One. I pretended to be one of reporters on the radio, barging in with my microphone.

“I’m now standing in the living room of the Honorable Papa Kamkwamba,” I said, in a deep, serious voice. “Mister Kamkwamba, this room used to be so dark and sad at this hour. Now look at you, enjoying electricity like a city person!”

“Oh,” said my father, smiling. “Enjoying it more than a city person.”

“You mean because there’s no blackouts and you owe ESCOM nothing?”

“Well, yes,” said my father. “But also, because my own son made it.”

H

AVING LIGHTS AT NIGHT

was a remarkable improvement in my family’s life. However, it still wasn’t perfect. The battery and wires I used were not the best quality. The wire Charity had given me had run out, so I was mainly using bits and pieces of wire I’d found in the scrapyard. Some of these wires were never meant for electricity, but I used them anyway. My patchwork of fused-together wires weren’t covered in plastic insulation, but were bare and often sparked when I connected them to the battery terminals. Since I didn’t have a proper conduit to house them, the positive and negative wires leading from the bulbs and switches were simply nailed to the walls and across the ceiling like a heap of Christmas lights. I took great

care not to cross them, since my poor roof was made from wood and grass and could easily catch fire.

Worse, the blue gum poles that supported the thatching had long been infested by termites. Each night, I went to bed hearing the sound of their teeth nibbling away, only to wake up in the morning to little piles of sawdust on the floor. Their constant appetite had finally hollowed the beams, causing them to sag a bit. Having a mess of bare electrical wires strung across these beams made it even more dangerous. It wasn’t long before it nearly caused an accident.

One afternoon after a big storm, I returned from Geoffrey’s house and discovered that the beam had finally broken, probably from the wind pushing on it. My ceiling now sagged in the middle and my floor was covered in dirt and grass. The broken beam had also dumped hundreds of squirming termites onto the floor and across my bed.

At first I tried sweeping them off, but there were so many. By that time, my father had managed to purchase a few more chickens, and as I looked out my open door, I saw a gang of them walking past.

“Come here, chickens,” I called out. “Do I have a treat for you!”

I tossed a few termites out the door to lure them in. Once they realized what a great bounty was waiting for them inside my room, they went mad with hunger. Soon my floor and bed were filled with chickens, squawking and flapping their wings with excitement as they pecked at the helpless termites.

“Get them all!” I shouted. “I don’t want to see another one alive!”

The termite incident caused such a commotion that I didn’t even notice the smell of something burned. After the chickens cleared out, I looked closely at the broken beam that hung from the ceiling and saw that my wires had crossed during the collapse. Instead of starting a fire, they were so cheap and thin they’d simply melted and snapped in two. I thanked God no one had been hurt.

Geoffrey came over and we stared at this mess together.

“

Eh, bambo,

it’s a good thing I’m too poor to buy proper wire,” I said. “If I’d used anything better, I’d have burned up my home.”

“I warned you about the roof.”

“Sure, sure, but I didn’t listen.”

I

NEEDED A PROPER

wiring system, and as always, I returned to my

Explaining Physics

book and found just the model. Page 271 had a diagram of a mains system from a home in Britain. The drawing showed that when the wires ran from the main power supply, the first place they led was to a circuit breaker, which worked to kill the power when the circuit became overloaded. I needed one of these.

The circuit breaker in the diagram used fuses, which contained tiny metal filaments that melted when the overload occurred. I didn’t have any fuses, so like with everything else, I improvised by using what I had around my house. Instead of a filament and fuse system, I modeled my circuit breaker after the electric bell, which I’d also read about in the book.

An electric bell works when a coil suddenly becomes magnetized and pulls a metal hammer that strikes the bell. However, during this motion, the hammer also trips a switch and breaks the circuit, returning it to its original position. Of course, this happens about a dozen times per second.

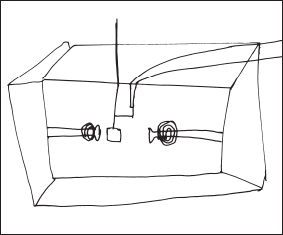

A drawing of my handmade circuit breaker, which I modeled after the electric bell.

I started my circuit breaker by constructing a breaker box using melted PVC pipe (as I’d done with my switches). I wrapped the heads of two nails with copper wire to create two electromagnetic coils, then mounted them inside the box, with the coils facing each other about five inches apart. Coming up through the middle, I placed a bar magnet (from a radio

speaker) attached to a bicycle spoke that could easily flip from side to side. I then took a spring from a ballpoint pen and stretched it out. I placed it between the bar magnet and nail to where it rested lightly against the circuit’s live wire. Basically, this spring completed the circuit and acted as a kind of trap.