The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind (26 page)

Read The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind Online

Authors: William Kamkwamba

The doctors at the clinic were so impressed by our enthusiasm they asked me to write a play to help persuade people to get tested. Over several days, I prepared a great production—more in my mind than on paper—which I titled:

Maonekedwe apusitsa.

Or simply:

Don’t Judge the Book by Its Cover.

The play was performed two weeks later in the trading center. Gilbert and I put up posters announcing the show, and even asked our new

chief—Gilbert’s cousin—to summon a few Gule Wamkulu to help draw the crowds. The morning of the play, we got our gang of actors together and marched through the trading center, shouting, “Come one, come all!! See the HIV drama! See the acrobatics of Gule Wamkulu!” We set up in the market center and soon, about five hundred people had gathered around. Many of the shops even closed during the performance.

The play involved a certain married couple in the capital Lilongwe (played by my friends Christopher and Mese). The husband sends his wife to the village to grow some maize. Well, as you know, life can be very difficult in the villages. People get hungry, the work is hard, and the sun is very hot. Not accustomed to this kind of farm life, the wife loses a lot of weight. When she returns home, the husband becomes angry.

“Why are you so thin?” he asks.

“The village is tough,” she says.

“You’re lying. I think you’ve been sleeping with other men and now you have AIDS.”

Little did the wife know, but while she was gone, her husband had been spending every night in the bars of Area 47, where he’d slept with many prostitutes.

The wife pleads her case with the husband, denying his accusations. But the husband doesn’t accept her story. “Go back to the village,” he tells her. “If you want to sleep around, then go and do it. Get out of my house!”

Luckily, a friend arrives just in time and sees them fighting. (This was my part.)

“Wait a minute, brother, what’s the problem?” he says.

“I sent this woman to the village to grow maize and look how thin she became. She says the farming was hard work, and there was no food in the village. But I say she has AIDS, and I’m not staying with her anymore!”

The friend says, “Brother, you can’t tell if someone has AIDS by just looking at them. It could be hunger, tuberculosis, or many other things. The only way to know is to be tested at the local Volunteer Counseling and Testing center.”

“Fine!” says the husband. “We’ll go down there and prove this once and for all.”

The husband thinks because he’s so muscular, all those prostitutes in Area 47 haven’t hurt him. But after being tested at the VCT center, sure enough, the doctor (played by Gilbert) informs the husband he’s HIV positive. His wife is negative.

“You’re cheating me!” he tells the doctor. “This can’t be true!”

“I wouldn’t tell you a lie,” the doctor says. “But don’t worry. This isn’t the end. You can still live your life if you play by a few simple rules.”

The wife becomes afraid. “There’s no way I can stay with you. You’re right, husband. I should leave.”

“Don’t be foolish,” says the doctor. “You can stay together. Just be careful and use protective measures.”

The wife is so relieved and gives her husband a hug. “I still love you,” she says. “I’ll stay with you until death do us part.”

When the play was over, the crowd shouted and cheered and threw handfuls of paper in the air. Once we actors cleared the stage, the Gule Wamkulu closed the show with an electrifying grand finale. I won’t say our little play inspired loads of people to be tested right away, but it did help change attitudes. These days, with the help of government programs and new VCT centers, more people are being educated and tested and AIDS isn’t such a taboo. Even the magic men started sending their clients to the clinics, preaching science and medicine over their charms.

My popularity as an inventor and activist soon attracted other opportunities. Not long after the play, one of the teachers at Wimbe Primary asked if I’d be interested in starting a science club for the students. He’d been impressed by my windmill and wanted me to build one on campus.

“The students look up to you,” he said. “Your skills in science will really challenge their brains.”

“Sure,” I said. “I’ll do it.”

The windmill I created at the school was small, much like my first radio experiment, with blades made from a metal maize pail and a radio motor for a generator. I attached it to a blue gum pole and ran the wires

into an old Panasonic two-battery radio that I’d repaired. I did this during recess one morning when all the kids were in the grove playing soccer. As I worked, a crowd gathered around to watch. When I connected the wires, the music blasted through the schoolyard.

“Keep quiet. I want to listen!” they screamed.

“Don’t push me!”

“Let me see!”

The windmill not only allowed students to listen to music and news, but they could also charge their parents’ mobile phones. Each Monday, I told them about the basics of science and explained the importance of innovation, like how ink was first made by using charcoal. I also demonstrated the cup-and-string experiment featured in my books, to help explain how a telephone works.

I walked them through the steps of how I’d built everything using simple scrapyard materials, and I hoped I’d inspire them to build something themselves.

If I can teach my neighbors how to build windmills, I thought, what else can we build together?

“In science we invent and create,” I said. “We make new things that can benefit our situation. If we can all invent something and put it to work, we can change Malawi.”

I later found out that some of the students had been so inspired by the windmill in the schoolyard, they went home and made toy windmills themselves.

I began to imagine what it would be like if all of those pinwheels had been real, if every home and shop in the trading center each had a spinning machine to catch the wind above the rooftops. At night, the entire valley would sparkle with light like a clear, starry sky. More and more, bringing electricity to my people no longer seemed like a madman’s dream.

I

N EARLY

N

OVEMBER

2006, some officials from the Malawi Teacher Training Activity were inspecting the library at Wimbe Primary when they noticed my windmill in the schoolyard. They asked Mrs. Sikelo, the librarian, who’d built it, and she gave them my name. One of them telephoned the head office of MTTA in Zomba, in the southern region, and told his boss, Dr. Hartford Mchazime, what he’d seen.

A few days later, Dr. Mchazime drove five hours to Wimbe. His driver took him to our house, where he asked my father if he could speak to the boy who’d built the windmill.

“He’s here,” my father said, and called me from my room.

Dr. Mchazime was an older man with gray hair and kind, gentle eyes. But when he spoke, his command of language was large and powerful. I’d never heard anyone speak such good Chichewa, and when he spoke English, it was simply inspiring.

“Tell me everything,” he said, asking me about the windmill and how it had happened.

I explained my windmill, as I’d done hundreds of times before, then took him through our house and demonstrated how my switches and the circuit breaker worked. He listened carefully, nodding his head, and asked specific questions.

“These are very tiny bulbs,” he said. “Why aren’t you using big ones?

“Big bulbs require AC power,” I said. “In order to have many lights, I have to charge a battery, which is DC. These tiny car lights are the only DC bulbs I could find.”

“How far did you go with your education?”

“I dropped the first year of secondary school.”

“Then how did you know this stuff about voltage and power?”

“I’ve been borrowing books from your library.”

“Who teaches you this stuff? Who helps you?”

“No one,” I said. “I’ve been reading and doing it alone.”

Dr. Mchazime then went to see my mother and father.

“You have lights in your house because of your son,” he said. “What do you think of this?”

“We’re proud,” my mother said. “But we thought he was going mad.”

Dr. Mchazime laughed and shook his head.

“I want to tell you something,” he said. “You may not realize, but your son has done an amazing thing, and this is only the beginning. You’re going to see a lot more people coming here to see William Kamkwamba. I have a feeling this boy will go far. I want you to be ready.”

The visit left me a little confused and very excited. No one had ever asked me such questions before, and no one had taken that kind of interest. That afternoon, Dr. Mchazime returned to Zomba and told his colleagues what he’d seen.

“This is fantastic,” they said. “The whole world needs to know about this boy.”

“I agree,” Dr. Mchazime said. “And I have just the idea.”

The next week, Dr. Mchazime returned to my house with a journalist from Radio One. It was the famous Everson Maseya, whose voice I’d heard for years, and here he was at my house to interview me.

“What do you call this thing?” he asked.

“I’m calling it electric wind.”

“But how does it work?”

“The blades spin and generate power from a dynamo.”

“And in the future, what do you want to do with this?”

“I want to reach every village in Malawi so people can have lights and water.”

Two days later, while waiting for the Radio One interview to air, Dr. Mchazime came again with even more reporters. These men represented all the great media organizations in Malawi: Mudziwithu and Zodiac Radio channels, the

Daily Times,

the

Nation, Malawi News,

and

Guardian News.

They poured out of the car with their cameras and tape recorders and flocked around the windmill.

For two hours, they moved through the house, elbowing and shoving one another to get the best pictures of my switches and battery system.

“You’ve had your time. Now it’s my turn!” they shouted.

“Move aside, my paper is bigger!”

Soon our yard was filled with crowds from the trading center who’d gathered around to gawk at the famous journalists who’d come to our village.

Journalists visit my village to write about my windmill. To us villagers, these men were like celebrities.

Photographs courtesy of Sangwani Mwafulirwa, Malawi Daily Times

“Look, it’s Noel Mkubwi from Zodiac!” they said.

“Finally we see his face. What a handsome man!”

“Look, he’s interviewing William!”

One of the reporters even climbed my tower and studied the blades and pulley system, taking pictures the whole time.

“Mchazime, this chap is a genius,” he shouted.

“Yes,” he answered, “and this is the problem with our system. We lose talent like this all the time as a result of poverty. And when we do send them back to school, it’s not a good education. I’m bringing you here because I want the world to see what this boy has done, and I want them to help.”

Dr. Mchazime told us that as a boy he had endured his own setbacks with education. His father had also been a poor farmer who’d struggled to feed and clothe his family. But his father had learned the value of an education. While working in the gold mines of Rhodesia, he’d been denied several opportunities because he’d never gone to school. That failure seemed to haunt him the rest of his life.

At one point when Dr. Mchazime was young, his family barely had enough to eat. He had volunteered to drop out of school and work so his brothers could go instead. His father refused, saying, “All of my kids will stay in school. I’ll do whatever it takes.” It took nearly ten years for Dr. Mchazime to complete his secondary education. When he was thirty-three years old, he was finally accepted with a scholarship to the University of Malawi in Zomba, later earning master’s and doctorate degrees from universities in America, Britain, and South Africa. Before working for the MTTA, he’d written many Malawian textbooks, including my own Standard Eight English reader.

T

HE DAY AFTER THE

journalists came to visit, the interview with Everson Maseya finally aired on Radio One. I was behind the house chatting with my aunt, when my mother shouted, “William, come quick. It’s coming on!”

My family all gathered around the radio, and I heard the announcer

say, “A boy in Wimbe near Kasungu has made electric wind.” When my voice started to come through the speakers, my sisters began to cheer.

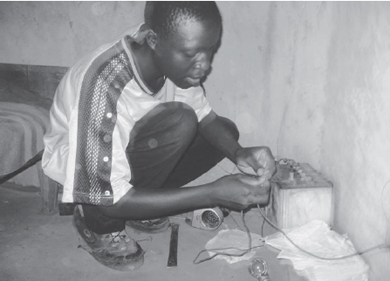

Here I am connecting the windmill to the battery for the journalists, trying not to burst out laughing. I was so nervous, but even more excited.

Photographs courtesy of Sangwani Mwafulirwa, Malawi Daily Times

If the radio show wasn’t enough good fortune, the story in the

Daily Times

was published the next week, with a big headline that said, “School Dropout with a Streak of Genius.” The story has a photo of me pretending to connect the wires to the battery in my room, while trying not to smile. That afternoon, I took the paper to the trading center to show everyone what the madman had done.

“We also heard you on the radio,” people said. “Did you have to go to Blantyre?”

“No, they came to me,” I answered.

“Really? We’re very proud. You represented us well, and we’re so impressed at how well you spoke.”

In a way, it took having these reporters come to my house to make our town finally accept my windmill. I don’t know, but I think it was a kind of

validation. After the radio and newspaper coverage, the number of visitors to my house increased tenfold.

Shortly after the story ran, I started some much-needed improvements on the windmill. I’d realized the big acacia tree behind the latrine was blocking my strongest wind and I needed to go higher. So with the

Daily Times

story under his arm, my father was able to convince the manager of the tobacco estate to part with several giant poles, which I used to build a tower that was thirty-six feet high. Once I moved it away from the tree, the speed of my blades doubled, and so did the voltage.

A

FTER VISITING MY HOUSE

with the reporters, Dr. Mchazime went back to Zomba and gathered his colleagues.

“I think this chap should be sent back to school,” he said. “He needs to continue his education and develop his abilities. That way these inventions will be credible and people will respect what he’s doing. Without education, he’s limited.”

“We agree,” one of his associates said. “Perhaps we can find an organization that can support him.”

“Eventually, yes,” Dr. Mchazime said. “But we need to put him in school as soon as possible. In this office, can we contribute something for his fees?”

Dr. Mchazime pulled out a wad of kwacha from his pocket and tossed it on the table. “Look, here’s my contribution, my own pay. Who will follow?”

By the end of the day, Dr. Mchazime had collected nearly two thousand kwacha.

That week, Dr. Mchazime contacted the Ministry of Education and asked them to find a good school for me to attend. No one answered his calls or letters, so he drove to the office of the head of secondary education.

“I sent a letter,” he told the official.

“We received your letter,” she said. “This boy has a very interesting story. We’ll find a place for him, but it can’t be now.”

“You people are delaying him,” Dr. Mchazime said. “He’s growing up, and the more you delay, the more schools will say he’s too old. Try to do this faster.”

The woman said they’d be in touch, but no one called back. Dr. Mchazime returned and was told to go to Kasungu, to see the division manager of central east schools. Dr. Mchazime got in his car and drove four hours to her office.

“I’ve read this kid’s story,” the woman said. “He’s very interesting.”

“Of course he’s interesting, so don’t waste his time,” Dr. Mchazime said. “He needs to be in school immediately.”

“There are procedures that must be followed,” she said.

“Surely you can make an exception. Surely there’s some kind of waiver?”

“Okay,” she said. “I’ll go see this windmill myself.”

While I was in the trading center running errands for my father, the manager of schools came to see my windmill, along with several people from the Ministry of Labor. They wore suits and their faces dripped with sweat as they stood in the hot sun. They didn’t explain why they were there—they just asked my mother if they could look around. An official from Labor then said to his colleagues, “This boy has special talent. We need to take him in the system. We need people like this in government!”

When the manager of schools returned to her office, she called Dr. Mchazime.

“You’re right,” she told him. “This boy needs to be in school, and we have just the place.”

“It must be a boarding school, one that specializes in science. Please don’t delay.”

“We’ll take it from here,” she said.

W

HILE THIS WAS HAPPENING,

something else amazing was taking place without my knowledge. The day after the

Daily Times

article ran, a Ma

lawian in Lilongwe named Soyapi Mumba brought the article to his office. Soyapi worked as a software engineer and coder at Baobab Health, an American-run NGO that’s working to computerize Malawi’s health care system, which is very unorganized with its stacks of old record books. One of Soyapi’s bosses, a tall American named Mike McKay, liked the article about my windmill so much that he wrote about me on his blog Hacktivate. That blog entry caught the attention of Emeka Okafor, a famous Nigerian blogger and entrepreneur, who was program director of a big conference called TEDGlobal 2007.

Well, Emeka wanted me to apply to be an official “fellow” at this conference, and for three weeks, tried very hard to find me. After harassing the reporters at the paper every day, he finally tracked down Dr. Mchazime. In mid-December 2006, Dr. Mchazime came to my home with the TED application. We sat down under the mango tree, and he helped me fill in the questions, plus write a small essay about my life. When he left, I still had no idea what TED was, or what it even meant (TED means Technology, Entertainment, and Design, and it’s an annual meeting where scientists, inventors, and innovators with big ideas get together and share).