The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind (28 page)

Read The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind Online

Authors: William Kamkwamba

Gerry was in Pittsburgh at the time of our visit, so Mike, Soyapi, and Peter Chirombo, Baobab’s hardware technician, gave us the tour. Mike happened to have a small windmill he’d built using an article in

Make Magazine

(now my favorite publication), which he was considering using to power a rural clinic. Its generator was a treadmill motor, which I’d never seen. Peter stuck a power drill in one end of the motor to make it spin, then took the two wires and attached them to a voltmeter—an amazing gadget! Using the voltmeter, I measured the motor’s power at forty-eight volts, which was four times stronger than my dynamo.

“What do you think?” Mike asked.

“Yah, it’s cool,” I said.

He then gave them both to me as a gift. The hole in heaven just seemed to be getting bigger.

Mike and Soyapi also taught me about deep-cycle batteries, which, compared to my car battery, provide a more stable amount of current for longer periods of time. I wanted to try one of these. So Tom and I went to the offices of Solair, a local solar-power dealer, and bought two batteries, four solar LED lamps, along with energy-saving fluorescent bulbs and materials to rewire my entire compound.

Workers came to my village the next week, and for three whole days, we replaced the old wire, dug trenches to bury the cables, and installed proper light fixtures and plugs (though I kept my old flip-flop switches just

for show). With new wire, plastic conduit, and buried lines, we never had to worry about starting fires again. I also stuck a lightning rod on top of the windmill just in case. Once finished, there was a bulb for every room, including two outside. Since the dark mud walls of our homes absorbed so much of the light, we painted them white for better reflection. I also installed solar panels on my roof to help supplement the power input. Eventually, every home in my village would have one of these panels, complete with a battery to store power. With each home lighted, the compound glowed at night.

A

FTER APPROACHING SEVERAL PRIVATE

secondary schools in the area and being turned down because of my old age, I was finally accepted at African Bible College Christian Academy (ABCCA) in Lilongwe, which was run by Presbyterian missionaries. The headmaster, Chuck Wilson, was an American from California, and my teacher, Lorilee MacLean, was from Canada.

Although I was behind most other high school students, Mrs. MacLean and Mister Wilson agreed to take a chance on admitting me. Mrs. MacLean had one condition: that when I left school each day, I didn’t go home to poverty. I had to find a good place to live in Lilongwe.

Since I didn’t have any relatives in town at the time, Gerry offered me a room at his place. At Gerry’s, I had my own bedroom and a desk for studying. The housekeeper, Nancy, also made sure I ate plenty of

nsima

and relish so I wouldn’t feel homesick. Everything was great, but because we were in the city, we experienced power cuts several times a week. I couldn’t help but think that after all that hardship to bring electricity to my village, here I was sitting in the dark in my success. Gerry said I should bring a windmill with me wherever I go.

Over time, Gerry became a great friend and teacher. He’d been a recreational pilot in England, then later worked on helicopters while living in Canada, so I always had many questions about engines and such. Sometimes after dinner, Gerry explained how helicopters worked, how the

spinning blades captured wind to lift the heavy machines, and how the back rotors kept them from spinning in circles. He also helped me with my English, particularly my

l

’s and

r

’s—something we Chichewa speakers always get confused. These lessons were sometimes done in front of the bathroom mirror, so Gerry could demonstrate.

“Okay, William, watch my tongue and say: ‘library.’”

“Liblaly.”

“L-i-b-R-a-R-y.”

“L-i-b-L-a-L-y.”

“You’ll get it.”

My class at ABCCA used a distance-learning curriculum from America that we learned by computer over the Internet. Just a couple months before I’d never even seen the Web, and now I used it every day to speak with teachers who were in Colorado. My high school class was small, only twelve people, including two Americans, a Canadian, a Korean, and a boy and girl from Ethiopia. A lot of Malawian children are in the primary school at ABCCA, but I was the only local high school student (the tuition was five thousand dollars per year, which most Malawians can’t afford). At first, I was a bit ashamed of my poor English, especially after hearing five-year-old children speak better sentences than I could. During my first few days, I became a little depressed. But my tutor, a Malawian named Blessings Chikakula, offered some great encouragement.

Mister Blessings had also come from a poor village near Dowa, where he’d worked as a primary school teacher, supporting his wife and four children on almost no pay. During the famine, the village suffered terribly and people died, including his father and several of his students. So, desperate to feed his family and give them something better, he’d caught a minibus to Lilongwe to join the Malawian army. But just as he was about to enter the gates, he received a call from his cousin, who told him that a scholarship application Blessings had submitted months before to ABCCA had been accepted. Later, when he was thirty years old, Blessings had stood proud before his wife and four children and walked across the graduation stage. The school then hired him as a teacher.

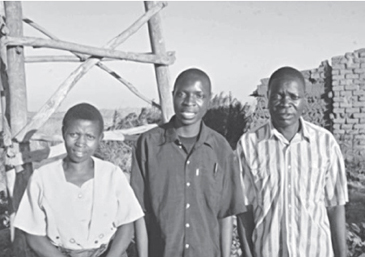

Me and my parents standing next to my windmill in 2007, just after I attended the TED conference.

Photographs courtesy of Tom Rielly

“Don’t be discouraged and give up just because it’s hard,” Blessings told me. “Look at me. I didn’t go to college until I was thirty. Whatever you want to do, if you do it with all your heart, it will happen.”

Eventually, the money from my donors allowed me to help my family in many other ways. I installed iron sheets on every relative’s home in our village to replace the grass thatch. I got mattresses so my sisters no longer had to sleep on grass mats on the dirt floor, plus covered water buckets to keep our drinking supply safe from pests. I bought better blankets to keep us warm at night in winter, malaria pills and mosquito nets for the rainy season, and I arranged to send everyone in my family to the doctor and dentist. (After never having seen a dentist in my life, I had only one cavity!)

And for once, I finally managed to repay Gilbert for all the help he’d given me. After Gilbert’s father died, Gilbert had to drop out of school because the family couldn’t afford to send him. So with my donations, I

put Gilbert back in school, along with Geoffrey and several other cousins who’d dropped out during the famine. I even sent the neighbors’ kids back to school.

And after years of dreaming about it, I was finally able to drill a borehole for a deep well, which gave my family clean drinking water. My mother said this saved her two hours each day carrying water from the public well. Using a solar-powered pump, I filled two five-thousand-liter water tanks and piped them to my father’s field. I then installed easy-assembly drip lines purchased from an American company called Chapin Living Waters, which finally allowed my father to plant a second maize crop. The storage room will never be empty again. The spigot from the borehole—the only automatic water system for miles around—is also free for all the women in Wimbe to use. Each day, dozens of them come to my home to fill their buckets with clean, cool water without having to pump and pump.

During holidays off school from ABCCA, I constructed a bigger windmill that pumped water. That pump now sits above the shallow well at home and irrigates a garden where my mother grows spinach, carrots, tomatoes, and Irish potatoes, both for my family to eat and to sell at market. Finally, the dream had been realized.

My family couldn’t have imagined that the little windmill I built during the famine would change their lives in every way, and they saw this change as a gift from heaven. Whenever I came home from school on weekends, my parents had a new nickname. They called me Noah—like the man in the Bible who built the ark, saving his family from God’s flood.

“Everyone laughed at Noah, but look what happened,” my mother said. “He saved his family from destruction.”

“You’ve put us on the map,” my father said. “Now the world knows we’re here.”

I

N

D

ECEMBER

2007, I went to the United S

TATES

to visit Tom for the Christmas holidays and to see the windmills of Southern California that

appeared in my book. After some difficulty getting a visa—it’s never easy for us Africans to travel to Europe or America—I landed in New York City right in the middle of winter, wearing only a sweater. The woman at the airline counter then told me that they’d lost all my luggage.

“We’ll call you,” she said.

I wondered how. I didn’t even have a phone.

In the taxi from the airport, I finally saw the great American infrastructure I’d read so much about. We drove over smooth roads with five lanes in each direction, across bridges with no water underneath, followed by more roads and more bridges. The tall buildings in the distance appeared so strong and pressed together. It was hard to imagine that men had built these things and a person could even walk between them.

It just so happened that Tom lived in one of those buildings in lower Manhattan. His apartment was on the thirty-sixth floor, and I wondered how I would ever get up there. Someone then showed me the elevator, which took me up in ten seconds just by pushing a button. Looking up, I saw that there was even a mirror on the ceiling. Already, I had so many questions.

Inside, the apartment was surrounded in windows from floor to ceiling, looking as if you could walk right over the edge. Before that day, the highest I’d ever been was the top of my windmill. It took me some time to adjust, and that night on the sofa, I had trouble sleeping.

Tom had to work a couple of days that week so several of his friends volunteered to show me around the city. One of them had arranged for a pile of warm clothes to be waiting when I arrived from the airport—complete with a winter coat, gloves, a scarf, and a hat so I wouldn’t freeze. I was so grateful, especially because everything I owned was lost someplace in Africa.

The next day, another friend—a famous dancer named Monica Gillette—picked me up for a sightseeing tour of Manhattan. Down in the subway, I watched people enter the gates using sliding cards—what a great idea. Traveling through the tunnels with the giant buildings above our heads, I was amazed that they never fell on us. The sidewalks of New York

left me exhausted, with hundreds of people running in every direction. One of the things I noticed in New York is that people don’t have time for anything, not even to sit down for coffee—instead, they drink it from paper cups while they walk and send e-mails.

Standing at a construction site, I watched giant cranes lift enormous pieces of steel into the sky, and it made me wonder how Americans could build these skyscrapers in a year, but in four decades of independence, Malawi can’t even pipe clean water to a village. We can send witch planes into the skies and ghost trucks along the roads, but we can’t even keep electricity in our homes. We always seem to be struggling to catch up. Even with so many smart and hardworking people, we were still living and dying like our ancestors.

The nice lady who’d donated my warm winter clothes was named Andrea Barthello, and she and her husband, Bill Ritchie, run a company called ThinkFun that makes cool educational toys and puzzles. I’d met her at TED, along with their son Sam, who was my age. The next day, Andrea and Sam took me on another tour of Manhattan island—this time by helicopter! Inside the chopper, the pilot let me wear headphones and sit up front near the instrument panels, dials, switches, and screens. Our glass bubble took us high above the city, above the Statue of Liberty, past the Empire State Building and speedboats on the river leaving their long trails of white. I couldn’t stop grinning.

Later that week, Tom and I drove to Connecticut to have dinner with Jay Walker and his wife, Eileen, whom I’d met at the TED conference. The library in Jay’s home is famous throughout the world, a kind of museum of great inventions. Many of his books were hundreds of years old and written on whatever materials were available, showing how even in other parts of the world, people went to great trouble to expand their knowledge. Some of the books were even covered in jewels. But the library was more than just books: an original Soviet Sputnik satellite hung from the ceiling, and displayed on a shelf were some of the first computers, radios, and processors, even a Nazi Enigma code machine. But my favorite item was a replica of Thomas Edison’s first lightbulb, which I studied from every angle. I’d

had a hard enough time creating light from a windmill. But

my God,

this man had created the actual light!

To think, my journey had begun in my tiny library at Wimbe—its three shelves of books like my entire universe. But now standing here, I was seeing the true size of the world, and how little access I had to it. There was so much to see and do. I felt a bit light-headed.